27 August 2023

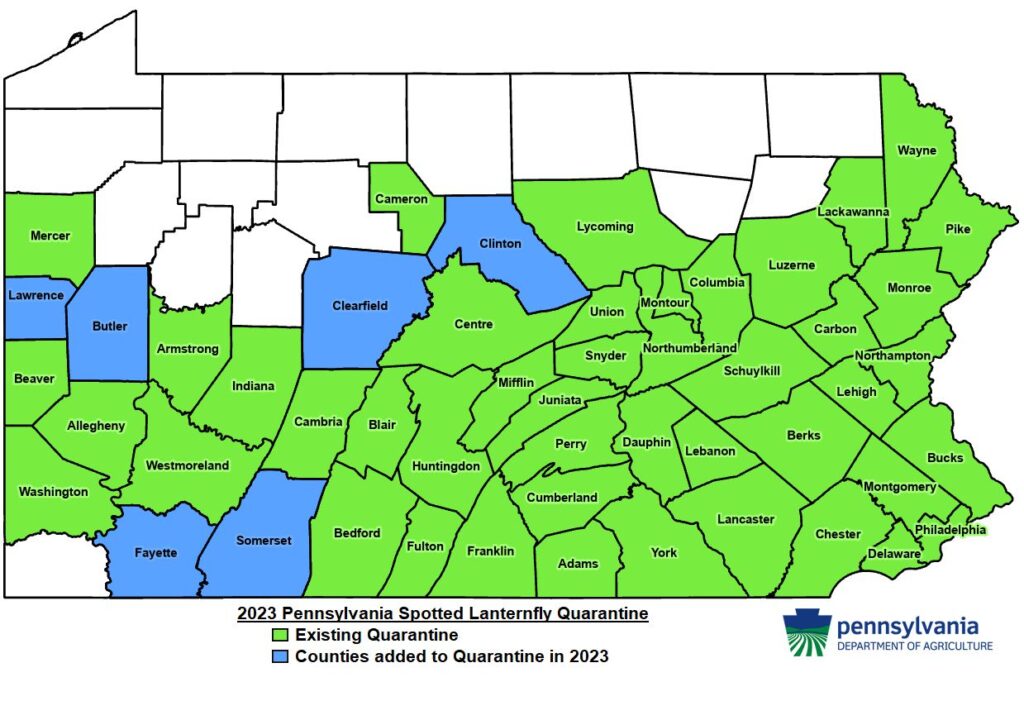

In Schenley Park’s Panther Hollow there are only a handful of Ailanthus altissima trees (Tree of Heaven) which I rarely paid attention to until recently. A couple of weeks ago I noticed that the plants and ground beneath those trees were wet, though it had not rained. This week the leaves and ground are black. Both phenomena are a by-product of the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) invasion.

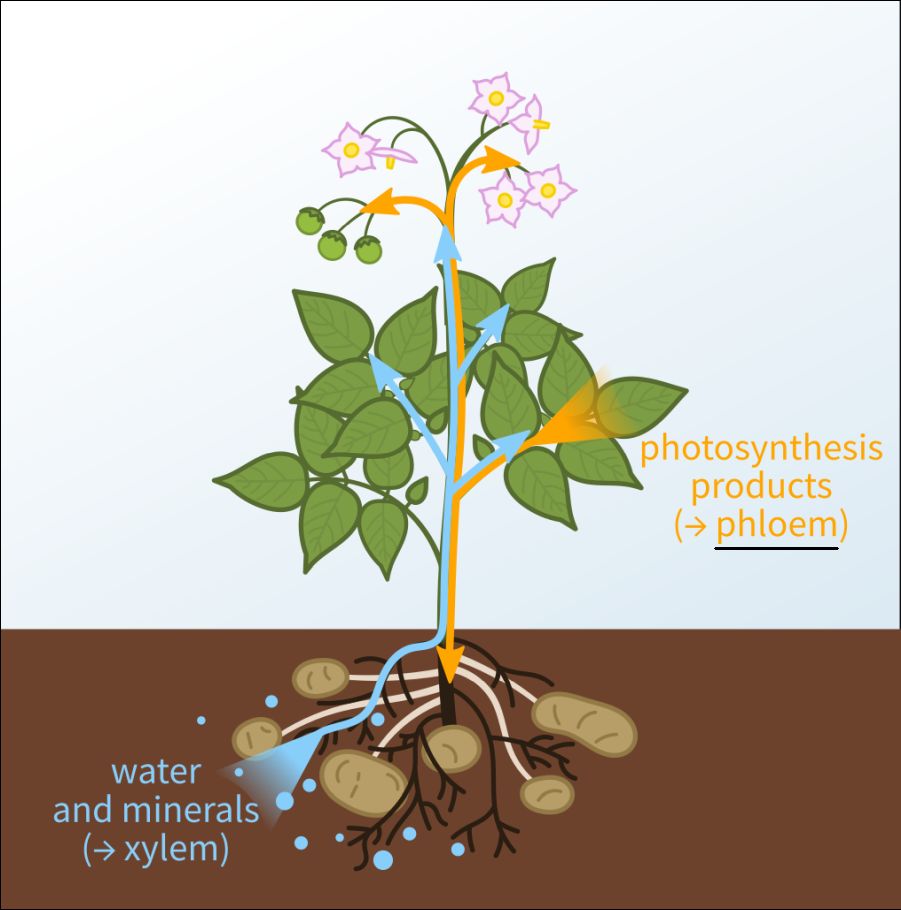

Spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) are sucking insects that pierce the bark of their host plant, Ailanthus, and sip the sugary phloem that travels from the leaves to the rest of the plant. (Phloem flow is orange in the diagram below.)

Everything that eats excretes and spotted lanternflies are no exception. Their watery “poop” is called honeydew because it is full of sugar.

If there were only a few lanternflies we would never notice the honeydew but when a large number coat a tree the honeydew is hard to miss, especially for the consumers of honeydew: bees, wasps, hornets, ants and butterflies.

Sugary honeydew eventually grows sooty mold. Everything with honeydew on it turns black.

Sooty mold is a fungus that appears as a black, sooty growth on leaves, branches and, sometimes, fruits. It is non-parasitic and not particularly harmful to plants apart from being unsightly. Potentially, it could affect the plant’s ability to use the sun for photosynthesis. If you can rub the black growth off with your fingers, it is probably sooty mold. If you cannot rub it off, it is most likely something else.

— Univ of Hawaii Master Gardener Program: FAQ, Sooty mold

Eventually white mold may cover the honeydew. I haven’t seen this yet but I’m watching for it.

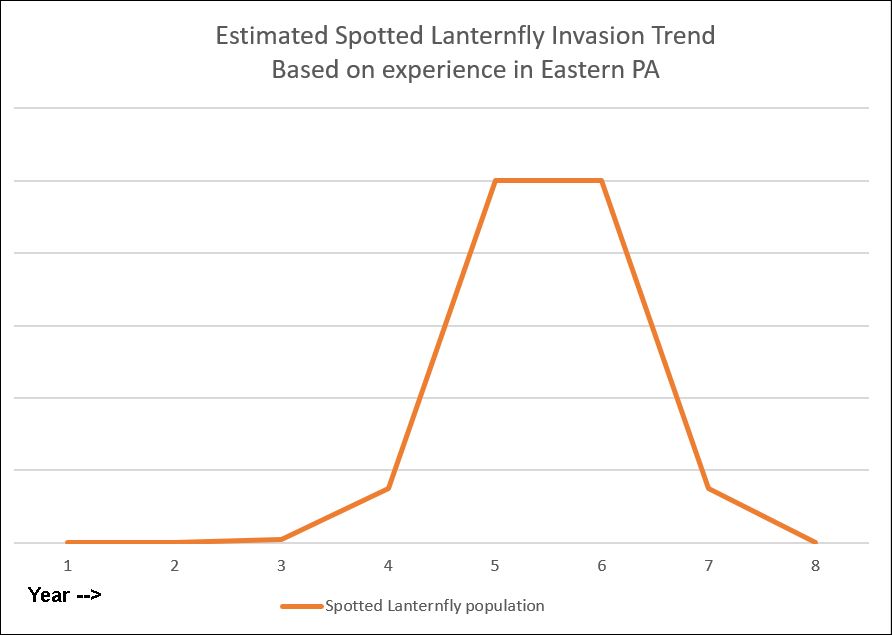

Will we ever be free of spotted lanternflies? Yes! Check out this blog This, Too, Shall Pass.

(photo credits are in the captions with links to the originals)