22 July 2023

Other than a few thunderstorms it’s been a quiet week in Pittsburgh.

At the Cathedral of Learning the garden beds are beautiful with begonias while the peregrines, Carla and Ecco, hang out and finish molting. The pair is no longer courting but sometimes bow together — less than once a day in late July.

On Thursday I was lucky to find the right mix of sun and shade to show off eastern enchanter’s nightshade’s (Circaea canadensis) bur-like fruits. They are notoriously difficult to photograph.

On 13 July a brief storm blew through Pittsburgh and broke this more than 100 year old London plane tree near Carnegie Library.

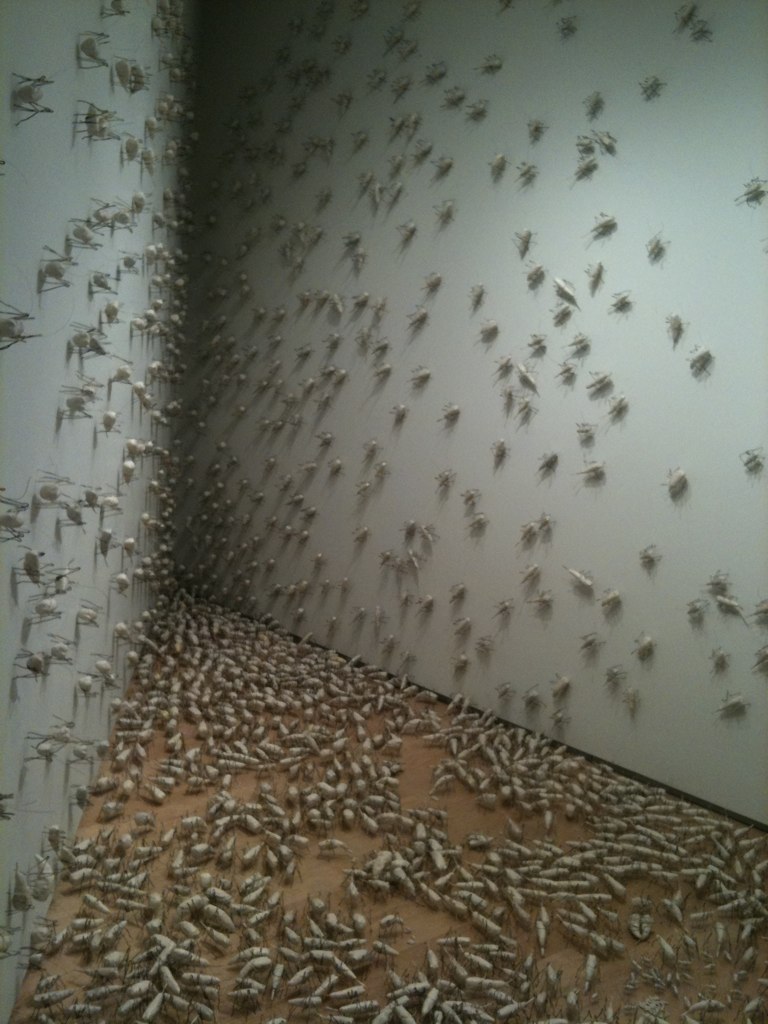

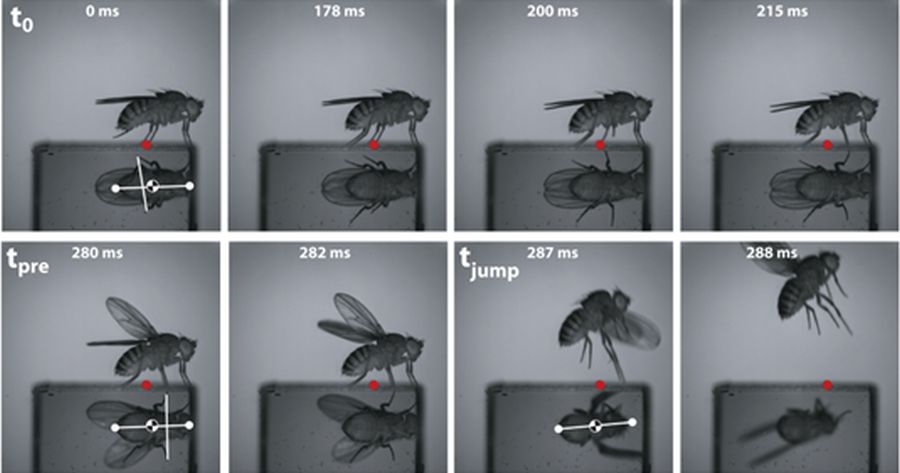

Meanwhile spotted lanternfly (SLF) red nymphs are everywhere, soon to become winged adults. I found thousands of them along the Allegheny River Trail near Herrs Island plus three adults, the first I’ve seen this year. This winged adult probably just emerged from the crumpled exoskeleton above it. Eewwww!

A few people along the trail were stamping on the nymphs and might have been recording their victories in the Squishr app (described here by WHYY). However, as Howard Tobias remarked a few weeks ago, “Tramping on spotted lanternflies is like trying to empty the ocean with a spoon.”

Are you upset by the bugs? Go hit the Panic Button at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in the Main branch Music Department, 2nd floor. This Panic Button, built into a bookcase, used to be part of the old security system but was disconnected decades ago. Press it to your heart’s content. Very satisfying.

And don’t forget to …

(photos by Kate St. John)