6 August 2024

There’s a tiny bat in the eastern U.S. that’s even smaller than the little brown bat. The tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus), formerly called the eastern pipistrelle, weighs only 0.16 to 0.23 ounces making it 30% smaller. Tricolored bats, like so many U.S. bats, are declining rapidly due to the fungal disease white nose syndrome and are Endangered in Pennsylvania. It’s pretty amazing that two of these tiny bats showed up in Downtown Pittsburgh in the past two years. We know this because both were rescued and rehabilitated at Humane Animal Rescue of Pittsburgh’s Wildlife Center in Verona (HARP).

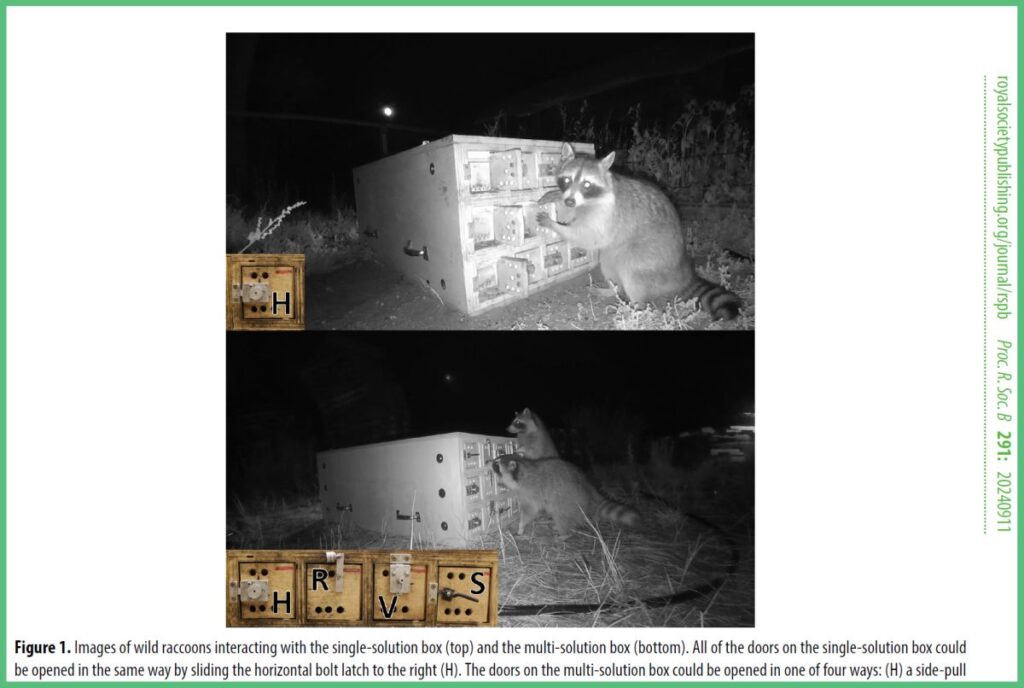

To give you an idea of the tricolored’s size, here’s one roosting in a bat cave in North Carolina.

Before the two bats were found in Pittsburgh, there was no known record of their occurrence here. A female and a male came separately to HARP many months apart so there are probably more of them but who knows where?

Almost a year ago the male arrived at the Wildlife Center.

On August 22nd [2023] we received a male Tricolored Bat…a bat we never would have thought to ever come through our door! Tricolored Bats are an Endangered Species here in PA. Aside from being moderately emaciated and dehydrated, he sustained no other serious injuries. Weight gain was our main goal, he was 5.2grams at intake and the goal was to get him to at least 7.0grams before release.

— Humane Animal Rescue of Pittsburgh Wildlife Center: 2023 Summer Releases

He was fed the tiniest mealworms, gained weight, and was soon ready for release. HARP points out that bats cannot take off from the ground. “In order for a bat to fly, first it must climb to a high place and then it launches itself by intentionally falling into the air!” Here he walks out of the sheltering blanket, up the tree, and he’s off!

Sometimes we only discover that a species is near us when it needs our help.

Learn more about the HARP Wildlife Center in Verona on their website and Facebook page. Read about their late summer wildlife releases in 2023 here.

(*) p.s. The bat is called tricolored because each hair on its back has three color bands, like a tabby cat hair. The bat is not striped. All the tips are reddish brown.