1 December 2023

What frightens a mountain lion (Puma concolor) enough to make it run away?

This video from a camera trap in Whatcom County, Washington provides the answer.

(credits are in the captions)

1 December 2023

What frightens a mountain lion (Puma concolor) enough to make it run away?

This video from a camera trap in Whatcom County, Washington provides the answer.

(credits are in the captions)

10 November 2023

“Hey!” says the great egret as it chases the cattle egret. “That’s my mouse!”

Cameras capture birds and animals in surprising ways. A stack of shorebirds. A bobcat on a prickly perch.

And deer running from …?

In New Jersey a buck ran through a front yard, jumped over two cars, and miscalculated the landing. Despite that he hopped out of the truck bed and ran away.

This month deer are still in the rut and still running into traffic. Caught in the act.

(credits are in the captions)

3 November 2023

This week is the coldest we’ve had since last March or early April. Squirrels are getting serious about winter in @YardGoneWild‘s North Carolina backyard.

(photo of squirrel in Woodbridge, VA from Wikimedia Commons)

19 October 2023

Do you feel thirsty when you wake up in the morning?

It turns out that as we exhale we also breath out water vapor, so during the hours of sleep we lose water. According to sleep specialist Dr. Michael Breus, the healthy solution is to drink a full glass of water in the morning before you drink coffee because caffeine is a diuretic.

We could avoid this by getting up in the middle of the night to drink water, but perhaps our bodies are compensating in another way …

(credits are in the captions)

1 October 2023

Fall migration has been intense over Pittsburgh lately and promises to be excellent tonight and tomorrow as well. Yesterday morning I went birding at Frick Park, expecting to find loads of warblers. No such luck. The birds flew over without stopping. However, for chipmunks it was a fantastic day.

Despite the current warm weather, chipmunks (Tamias striatus) are frantically gathering food to store in their underground burrows where they’ll spend the winter. Since they can’t use their paws to carry food, they fill their enormous cheek pouches.

What could possibly make their cheeks so fat? How about acorns?

With so many chipmunks scurrying in autumn, you rarely see two together. Chipmunks are antisocial but they like to make calls to warn each other of predators. Among their most common calls are two kinds of warnings.

Cheep or Chip: “Danger from the ground!” This call sounds almost like a bird and warns of nearby terrestrial predators such as a cat, fox, coyote or raccoon.

Tock or Knock: “Danger from the air! I see a hawk!” This is a useful call for birders that tells us to search for a hawk nearby. However, chipmunks know that hawks fly rapidly through the forest so all of them take up the call, far and wide, even though the hawk is not near them. Tock! Tock! Tock! Where is that hawk? Erf!

Read more about the chipmunk’s calls at North American Nature: What Sounds Does a Chipmunk Make?

(credits are in the captions)

29 September 2023

If you’ve been waiting to hear the elk bugling in Pennsylvania, now’s the time to make the trip to Benezette, PA.

In September and October Pennsylvania’s elk (Cervus canadensis) are in the rut, their annual period of sexual activity. The bulls gather harems, pursue the females, antler-spar with other males, and “sing” a bugling love song.

Like white-tailed deer, male elk grow new antlers every year but these cervids are huge. Males are 25% larger than the females and can weigh up to 1,100 pounds with antlers that can span five feet.

Consequently it’s a bit surprising that the bugle is such a high-pitched call. Its bell-like echoing carries far in the woods and fields.

This bull elk was recently seen through the thick morning fog, bugling loudly in a clearing in #ElkStateForest.@thePAWilds #PaElk #WildlifeWednesday #PaWildlife #OutdoorsInPa #FallInPa

— PA Department of Conservation & Natural Resources (@DCNRnews) September 27, 2023

? Elk making long high-pitched sound. pic.twitter.com/9khNBeM0xB

Visit the Elk Country Visitor’s Center in Benezette to see and hear the elk, perhaps even in the parking lot.

If you can’t be there in person, watch the Pennsylvania Game Commission’s live stream.

p.s. Elk, also called wapiti, were reintroduced in Pennsylvania in 1913 after we extirpated them in the late 1800s. Did you know white-tailed deer were reintroduced to Pennsylvania, too?

(photo by Paul Staniszewski)

2 August 2023

The Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) is the largest tiger subspecies and one of the most endangered animals on the planet. It nearly went extinct in the 1940s due to habitat loss and poaching, but conservation efforts in Russia allowed the population to increase to 400-500 in the wild. This map shows how their range contracted from the 1800s to the 2010s.

Saving the tigers requires knowing more about them but there are so few in the wild and they are so spread out that studying them would be too intrusive.

Instead a recent study of the dispositions of tigers interviewed the caretakers of 248 semi-wild tigers living in two large wildlife sanctuaries in northeastern China. The goal was to learn the the tigers’ personality traits, the traits that work well and those that don’t.

The research team invited more than 50 feeders and veterinarians to fill out questionnaires with lists of 67 to 70 adjectives that described tiger personality traits for each cat in their care. These words ranged from “savage” and “imposing” to “dignified” and “friendly.” The researchers designed the questionnaires to mimic human personality tests.

… Two distinct personality types emerged that accounted for nearly 40% of the tigers’ behaviors. Tigers that scored higher on words such as confident, competitive, and ambitious fell under what the researchers labeled as the “majesty” mindset. Those that exhibited traits such as obedience, tolerance, and gentleness were grouped together under the “steadiness” mindset. Together, these two personalities explained 38% of the behavioral differences displayed by the tigers in the study.

— Science Magazine: Tigers have distinct personalities according to big cat questionnaire

The study then matched the personality ratings of the individual cats to their success in life. “Based on their weights and eating habits, the tigers with majesty mindsets were generally healthier than those with steadiness personalities. They hunted more, mated more often, had more breeding success and appeared to have a higher social status than the steadiness tigers.” — Science Magazine

So for most of the tigers it comes down to Majesty …

or Steadiness.

Understanding their personalities will ease tiger-human interactions in the wild.

BONUS! When I researched this article I learned there are more tigers in captivity in Texas than in the wild. According to some estimates, there are 2,000 to 5,000 tigers in Texas compared to 3,900 in the wild (total of all tiger subspecies).

Compared to most other states Texas has generous (some say “lax”) wildlife-as-pets laws. Pet tigers are supposed to be registered in Texas and the owner must carry $100,000 in liability insurance but the number of registered tigers is lower than the actual number that live in the state.

For instance, take the Bengal tiger who roamed the streets of West Houston in May 2021. Houston is one of the few places in Texas where pet tigers are illegal so of course the 9-month-old tiger, named India, was not registered. The tiger caused a stir after he jumped out of his enclosure and walked around the neighborhood. The owner bundled him into an SUV and drove away, evading police (mistake! The owner was out on bond in a murder case). Eventually the wife turned over the tiger to police and it was given safe haven at the Cleveland Amory Black Beauty Ranch where there are other tigers. Read all about it in the Houston Chronicle: Everything we know about the tiger seen roaming a west Houston neighborhood.

p.s. What was it about escaped wild animals 2021? Three months later 3 zebras escaped in Maryland.

(photos and maps from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)

21 July 2023

Happy Friday! It’s time for wildlife’s own Candid Camera show.

Above, two young bobcats explore near a motion detection “camera trap” at Bosque del Apache. Below, a backyard cam caught the moment when a fox found a skunk in the dark.

At Melissa Crytzer Fry‘s video camera trap in the Sonoran Desert, a mother Gambel’s quail chased away danger. Turn up the sound and find out what upset her.

The moral of the story: do NOT mess with Gambel's #quail parents. Ever. #cameratrap ?up! pic.twitter.com/SXFhbtc9Ns

— Melissa Crytzer Fry (@CrytzerFry) July 4, 2023

A bobcat took a dust bath in front of the same camera.

One of our best #bobcat #cameratrap videos ever. #FelidFriday pic.twitter.com/tK0lMP87HS

— Melissa Crytzer Fry (@CrytzerFry) April 21, 2023

In the woods, two trail cams were bruised by black bears and lived to tell the tale. First, Mama and cubs:

Black bear mom with cubs pic.twitter.com/tNuf8ng2nX

— Dannyboy_westhawk (@DWesthawk) April 23, 2023

Then, a young bear scratched his back … on the camera housing.

— Dannyboy_westhawk (@DWesthawk) July 19, 2023

Smile, you’re on Candid Camera.

(tweets are embedded, photos are from Wikimedia Commons)

19 July 2023

Some fears, based on a species ancient experience, are bred-in-the-bone and guide behavior for millennia. For example, some people automatically fear snakes even though they never encounter them. This makes sense as an ancient fear spawned from early humans’ experience in Africa.

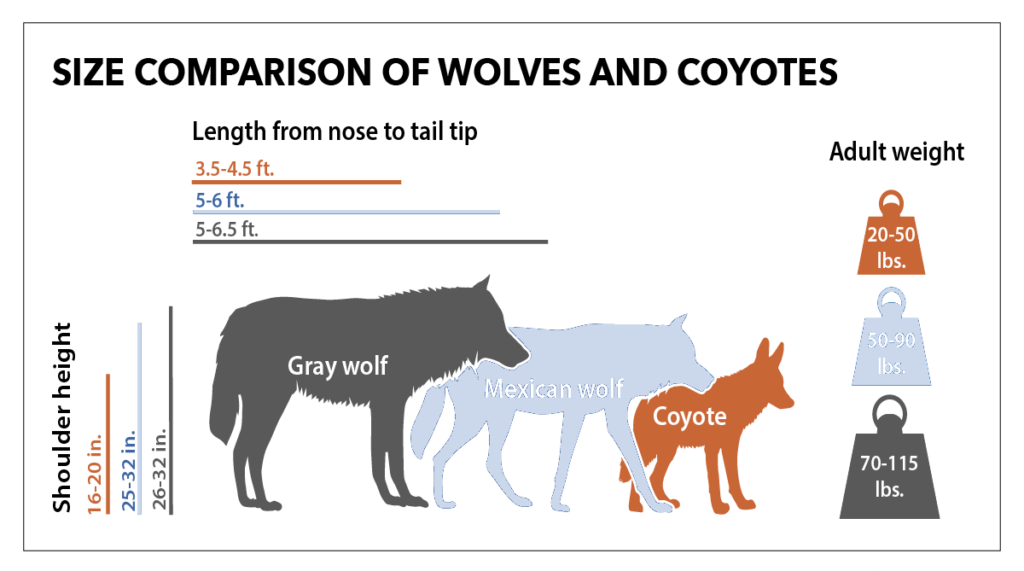

In the same way coyotes fear wolves. Coyotes are relatively small and hunt alone while wolves are twice the size and hunt in packs. A lone coyote can be eaten by wolves unless it manages to run away.

When wolves move in, coyotes leave the area and move closer to humans. Theoretically, the enemy of my enemy is my friend so humans would provide a shield against wolves.

Bobcats exhibit the same behavior in the presence of cougars, whom they fear.

Unfortunately, getting close to us is a bad bet for coyotes and bobcats with scant experience of humans. A recent study by Laura Prugh in northern Washington state, found that for 35 satellite tracked coyotes and 37 bobcats, the majority of those that died were shot.

Prugh’s work showed that in the case of coyotes and bobcats, gambling on safety with humans was a losing bet. Of the 24 coyotes that died, 14 were at the hands of people (13 shot and one roadkill). None were killed by wolves. Of the 18 dead bobcats, people killed 11. All told, a coyote was 3 times more likely to die at the hands of a human than in the jaws of a carnivore, the researchers found. For a bobcat, the odds were even higher at 3.8 times.

— Anthropocene Magazine: Coyotes gamble on human company to avoid wolves. It’s a bad bet.

Learn more in Anthropocene Magazine –> When coyotes gamble on human company to avoid wolves it’s a bad bet.

p.s. Yes, there are coyotes in the City of Pittsburgh. Those who live in cities are much better at coping with us. See Anthropocene Magazine: Coyotes live in almost all US cities.

(photos credits are in the captions, click the links to see the originals)

13 July 2023

What animal is most feared at a picnic? If a bear shows up it’s very frightening but if everyone shouts he’ll leave.

When it comes to fear this slow-moving docile animal makes everyone freeze in place. Oh no!

Don’t move! Don’t. Move.

Read more about skunks in this vintage article:

(photo credits in the captions)