13 November 2022

It’s mid November and the rut is at its peak in Pennsylvania. Bucks sniff the air for females in estrous (flehmen), chase does in heat, and hide with them in thick cover to breed repeatedly. Some run into traffic, including yesterday’s road-killed 6-point buck in Schenley Park. Meanwhile birders in Frick Park are seeing all of this up close. Very close.

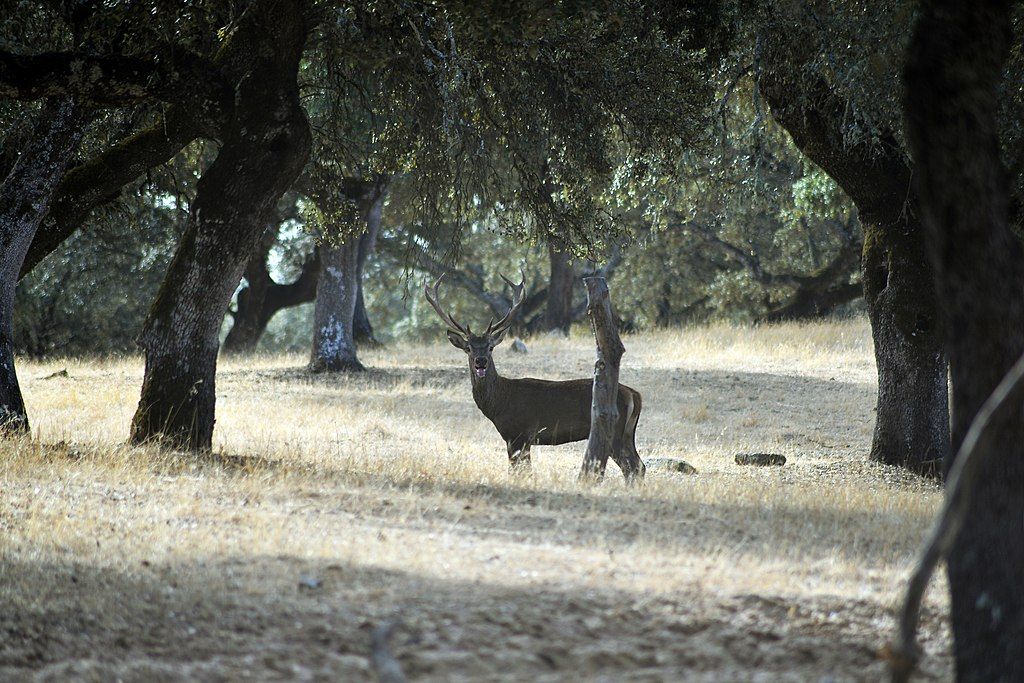

On 10 November Charity Kheshgi and I encountered a group of five. Two does and an 8-point buck were hiding in a thicket when a 4-point buck walked onto the trail behind us, sniffed the air and looked down at the females. Meanwhile another doe (at top) walked onto the trail ahead of us. This could have been dangerous for the two of us. Fortunately the deer did not view us as competitors.

The 8-pointer was hard to see in the underbrush but he resembled this 10-point buck Mike Fialkovich saw on 5 November that appears to be flehmening.

Deer are a prey species, alert to the presence and intent of predators. “Is the predator here? Is it hunting?” And they move to locations of least danger. We see them up close in Frick Park because they have learned that humans in Pittsburgh’s city parks are not dangerous even during hunting season.

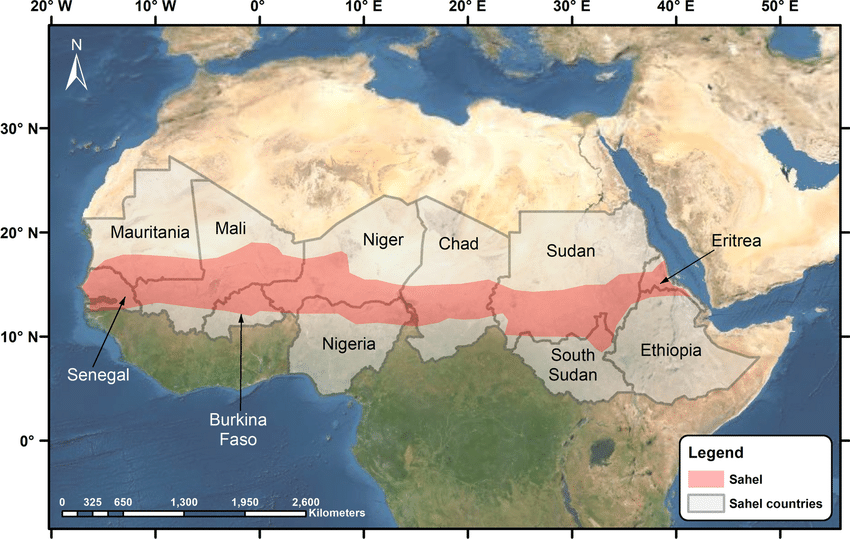

Meanwhile, hunting is currently in progress statewide and it’s good to be aware of it. We have so many deer in our area — Wildlife Management Unit (WMU) 2B — that hunting lasts longer here than in most of the state.

Here’s a quick summary of deer hunting times and types, now through January, in WMU 2B both Antlered and Antlerless unless otherwise noted.

- now – Nov. 25, including Sundays Nov. 13 and Nov. 20, WMU 2B: Archery

- Nov. 26 – Dec. 10 including Sunday Nov. 27: Statewide Rifle (“Regular firearms”)

- Dec. 26 – Jan. 28, 2023, WMU 2B:

- Archery

- Flintlock

- Extended Rifle season (Antlerless only).

Wear Orange and be alert for hunters! Note hunting on three Sundays in November.

p.s. When you’re on the road, watch for deer running into traffic, especially at dusk.

(photos by Charity Kheshgi and Mike Fialkovich, WMU map from PA Game Commission, calendar marked up from timeanddate.com)