9 March 2025

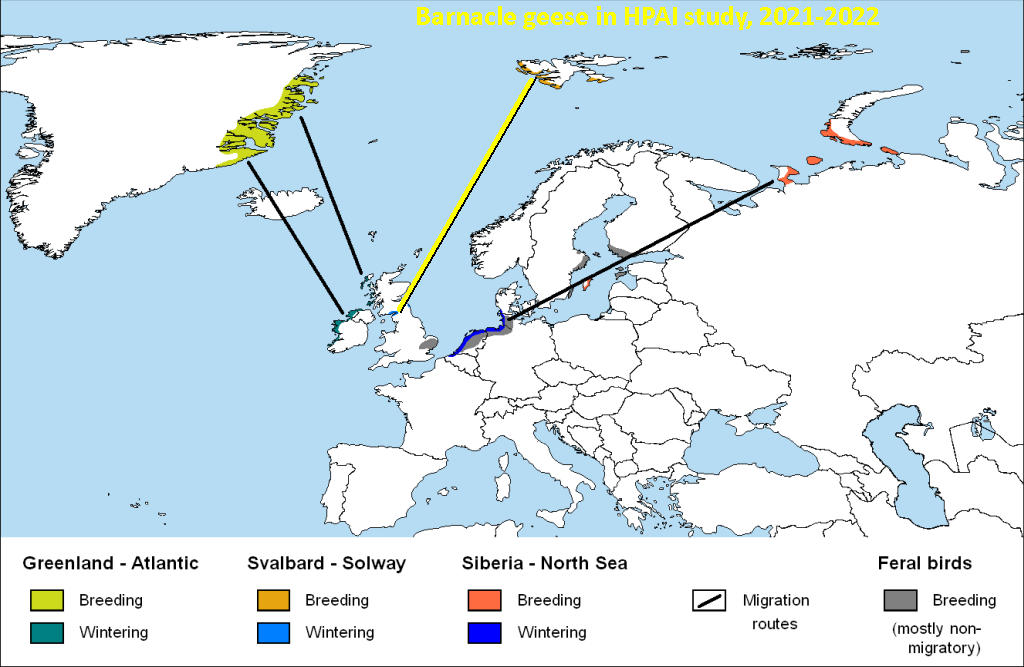

Every autumn barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) leave their arctic breeding grounds and migrate to Europe. In 2021-2022, those wintering at Solway Firth, UK(*) became infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 and 31% of them died. Even though their population had been devastated, they recovered to full strength in just two years. This can give us hope for North American birds hit hard by bird flu.

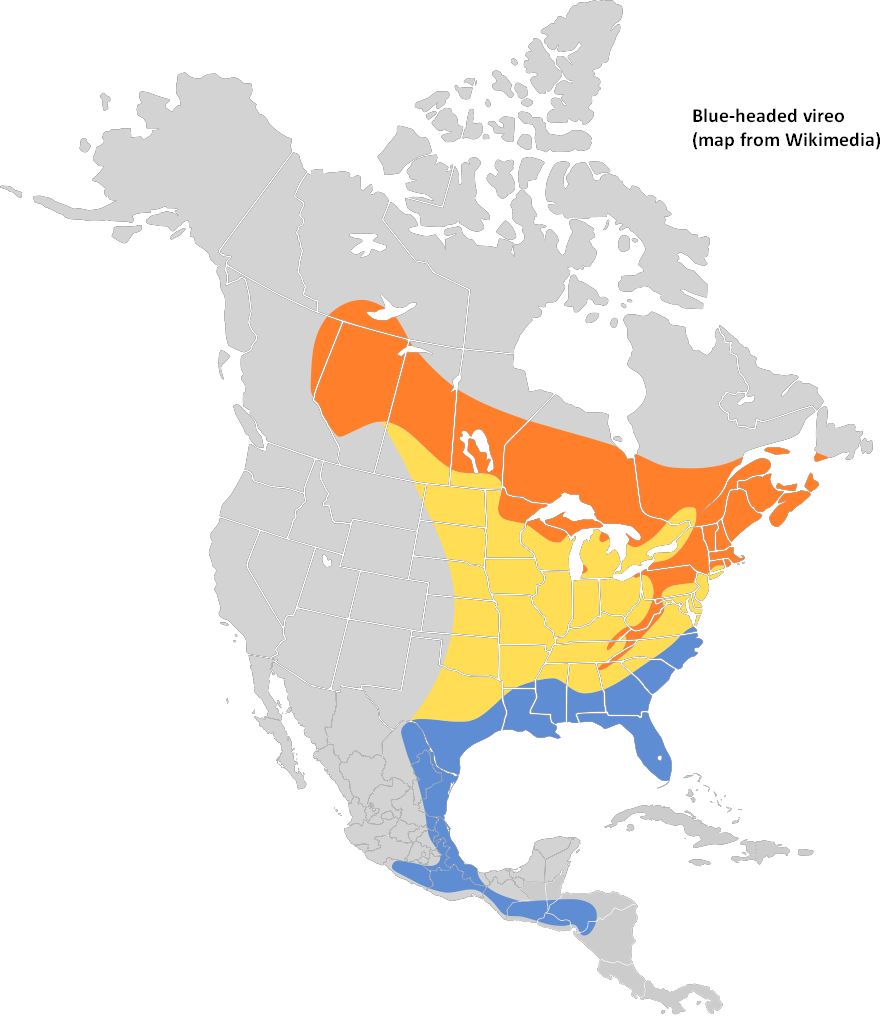

Wild barnacle geese breed in Greenland, Svalbard and Siberia yet each population has its favorite wintering site as shown on the map. Counts on the wintering grounds are directly tied to one breeding location.

The winter population at Solway Firth breeds at Svalbard.

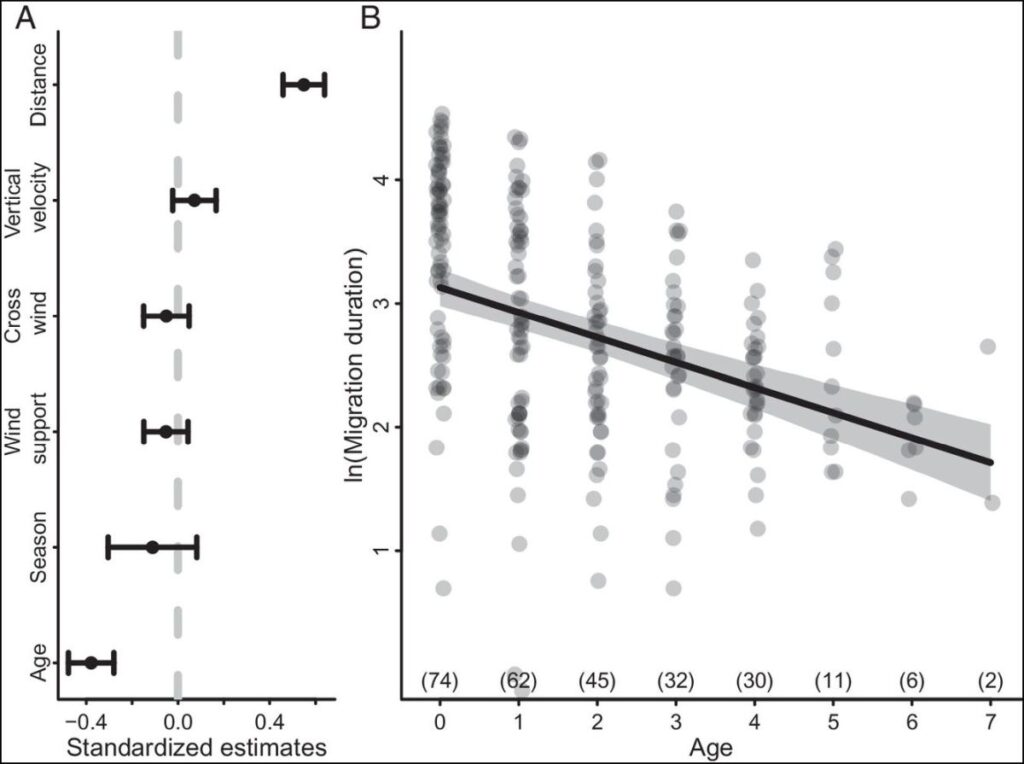

When bird flu hit Solway Firth in the winter of 2021-2022 researchers began a two+ year study to measure the demographic impact of the major HPAI outbreak on barnacle geese. During the outbreak they carefully counted dead goose carcasses and, thanks to fencing, were able to extrapolate for predation.

By February 2022 the barnacle goose population had dipped precipitously, but in the two years that followed the number of juveniles increased even faster. High birth rates on the breeding grounds quickly made up for the loss of adults.

Researchers speculated that …

The large impact of HPAI-related mortality on the Solway Barnacle Goose population was rapidly recovered, probably through a combination of the widespread development of natural immunity and high levels of breeding success in the years following the outbreak.

— Impacts of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) on a Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis population wintering on the Solway Firth, UK

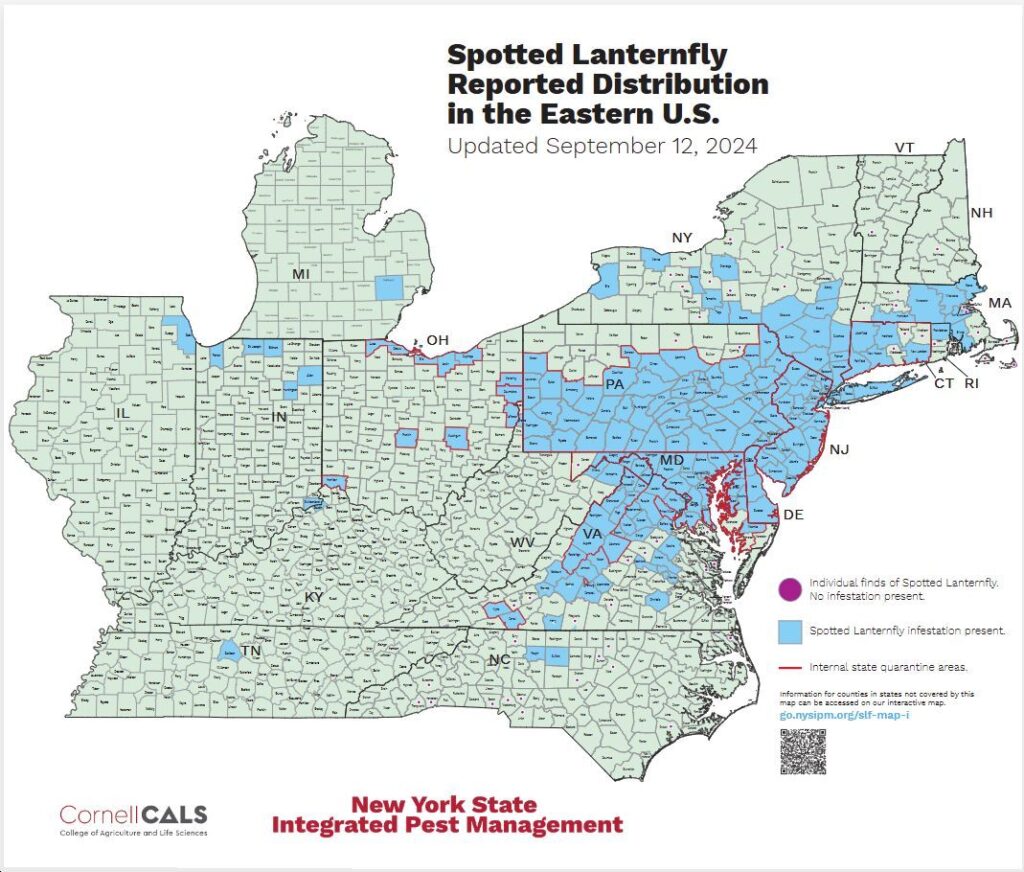

In Pennsylvania, snow geese have been hard hit with wild bird flu. It will be interesting to watch how their winter population fluctuates in the eastern U.S. in the years ahead.

p.s. We don’t have barnacle geese in the U.S. Here’s look like.

Barnacle geese (center of photo) look unique but are similar in size to their nearest relative the cackling goose.

Size comparison! Though cackling geese look like Canada geese they are much smaller. Thus barnacle geese are smaller than Canada geese we see in Pittsburgh.

(*) Solway Firth forms the western border of Scotland and England.