23 November 2020

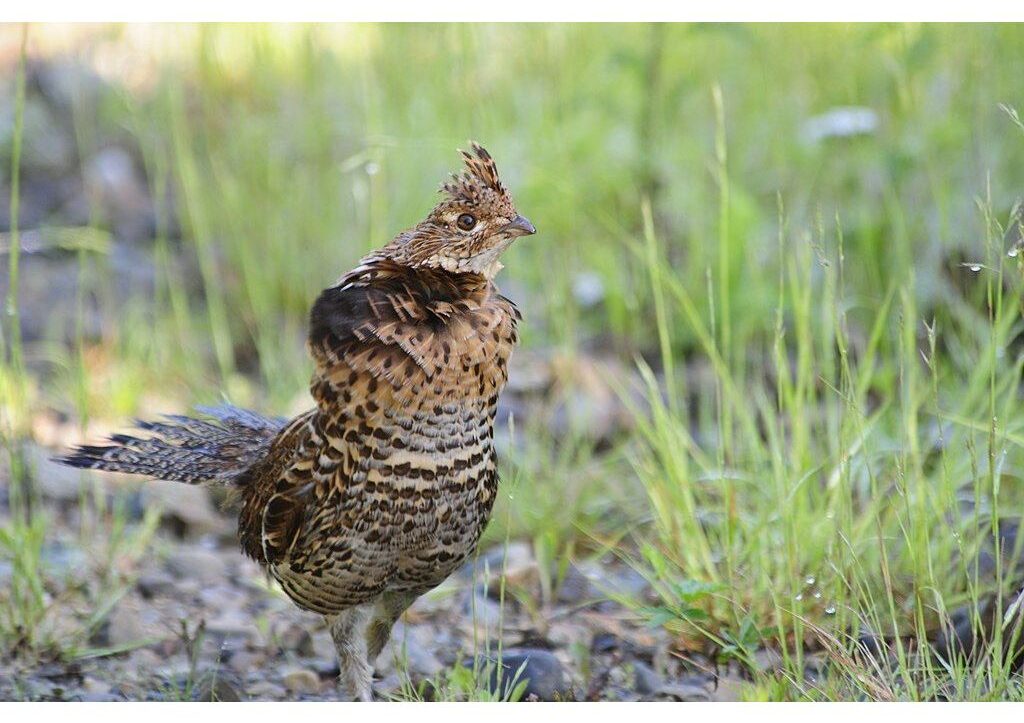

As we struggle with a nearly out-of-control coronavirus pandemic I was stunned to learn there’s an equally deadly virus among birds. The discovery came when I found the answer to Craig’s question: “Kate, why is the ruffed grouse population in decline in Pennsylvania? Habitat destruction?” No, West Nile Virus is killing them off.

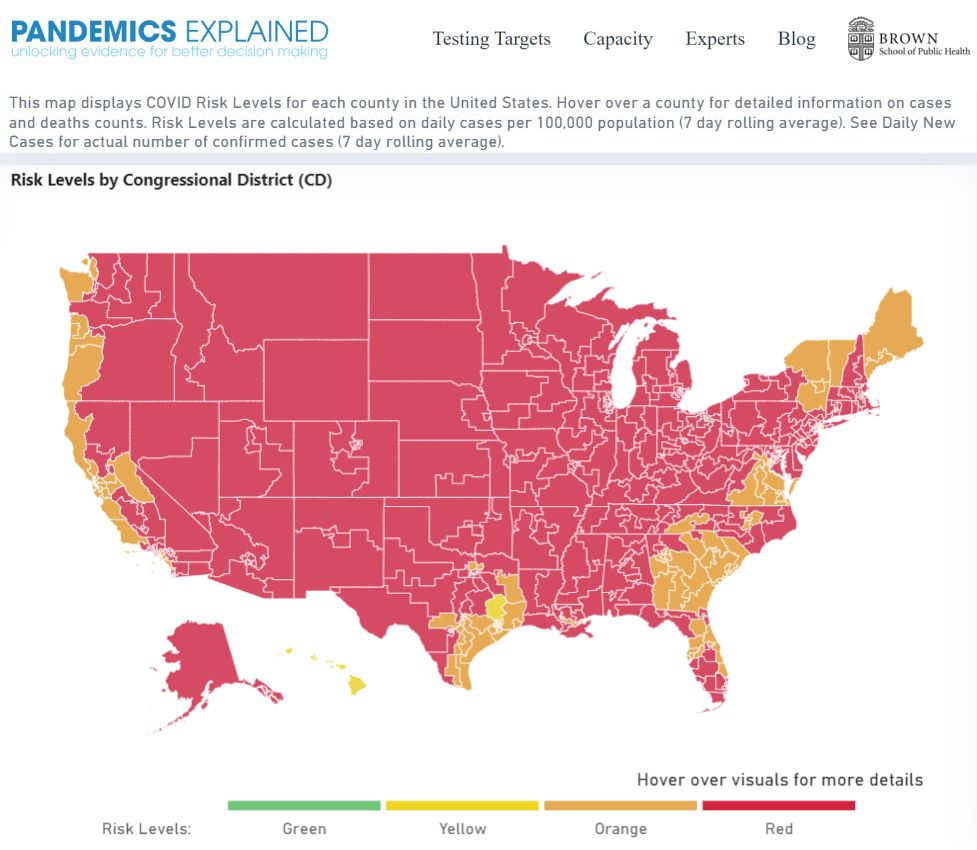

West Nile Virus arrived in North America more than 20 years ago and spread across the continent in just five years, killing native raptors and songbirds in its wake. When it struck Pittsburgh’s bird community in 2002 it was fairly common to find dead crows. That was a long time ago and I don’t see dead crows anymore so I thought birds were now able to survive the virus. Instead a 2015 study found that West Nile Virus is still wiping out birds in North America. It affects each species differently.

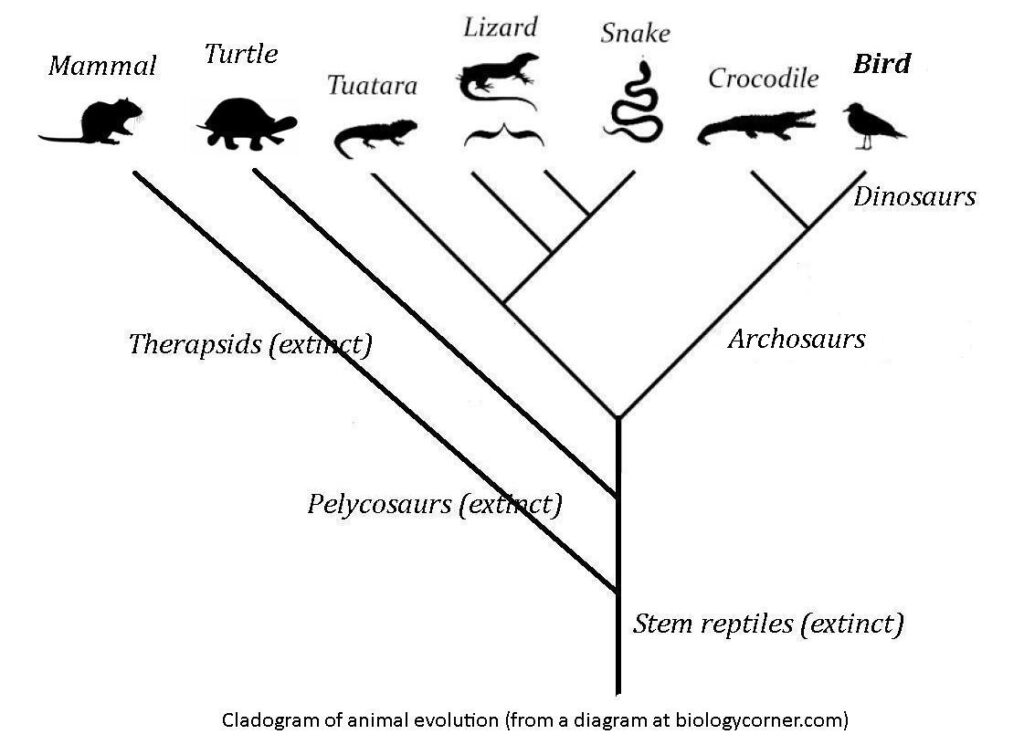

Some such as wild turkeys, chickens and house sparrows had a die-off when the virus arrived and then recovered with apparent immunity. Others never developed that resilience. The virus ravages their bodies so quickly that they die without reproducing.

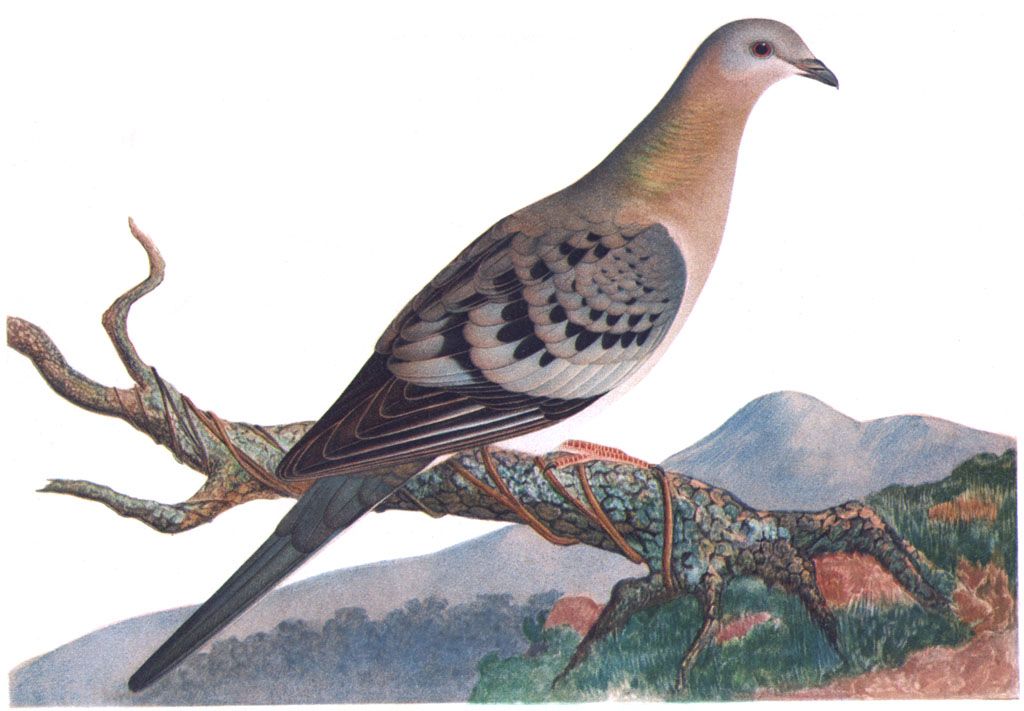

The birds in the slideshow above are some of WNV’s most devastated victims. Every year their populations decline in a downward spiral. Greater sage-grouse and yellow-billed magpies have such restricted ranges that WNV may push them to extinction. This explains why I haven’t seen so many warbling vireos, purple finches and American goldfinches as I did a decade ago.

In 2016 the PA Game Commission studied the plight of the ruffed grouse and found that infected grouse never before exposed to WNV had only a 10% survival rate. This 9-minute video tells the whole story.

It’s ironic that we worried so much about West Nile virus when it’s actually a bird disease. Read more about West Nile Virus In Birds at kenyon.edu.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons, J. Maughn, Steve Gosser and Chuck Tague,)