The 100th Meridian West is an imaginary line on the map that happens to mark the climate divide between the humid east and arid west in North America. Or rather, it used to. The rainfall divide is moving east.

Extending from the North to South Poles, the 100th runs longitudinally in the U.S. from North Dakota through Texas.

Its coincidence with the rainfall divide was first documented in 1877 by John Wesley Powell who found during his explorations in the Great Plains that the 100th was a visible boundary. Locations to the east of the 100th received 20+ inches of annual rainfall, the west received less.

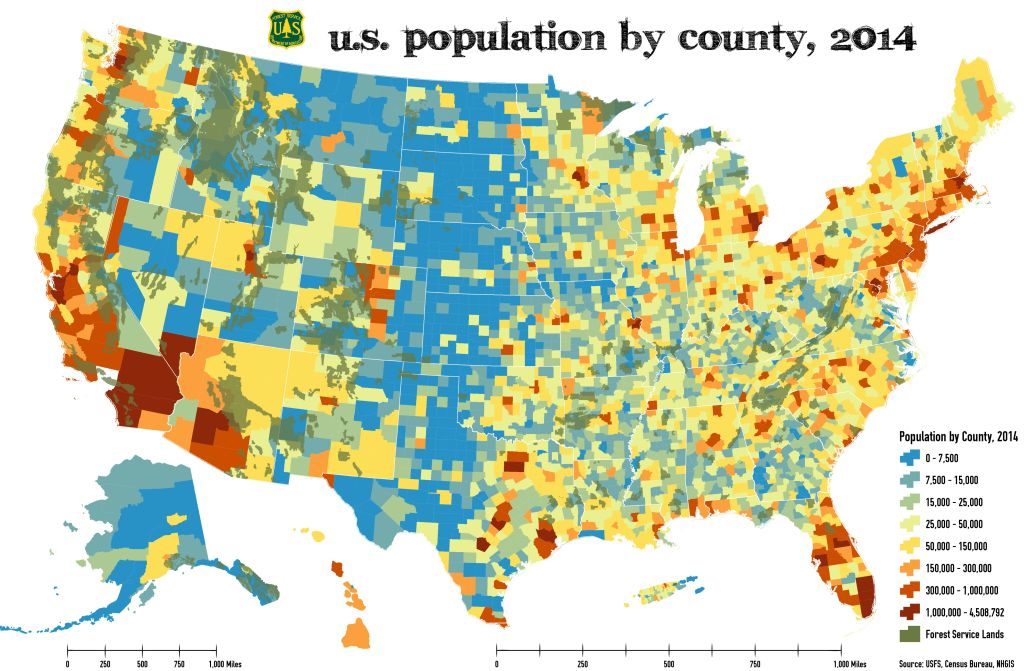

20 inches is a key number for agriculture and human population. It determines what you can grow, whether you have to irrigate and, thus, how many people can live there. Powell saw the line and told Congress it had implications for settlement of the western plains. Congress didn’t heed him but …

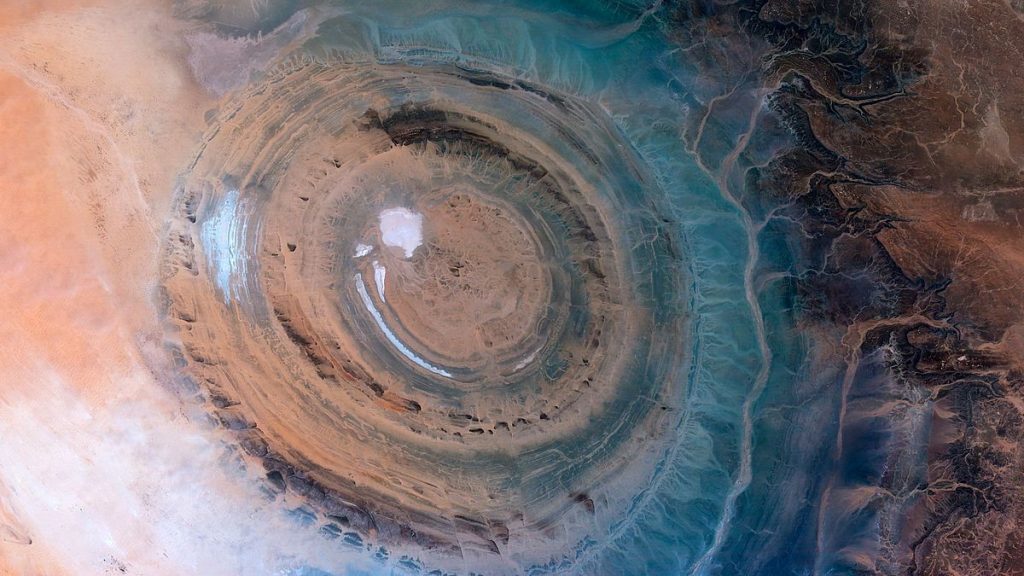

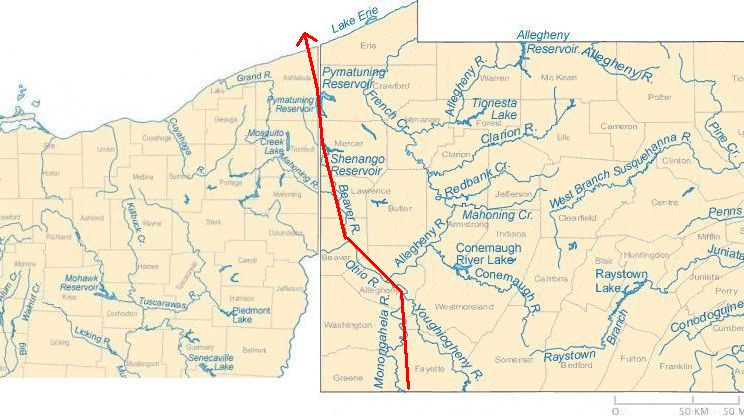

This 2014 map of U.S. Population by County shows that it played out as Powell expected. You can see the rainfall divide in population density. People choose to live where there’s water.

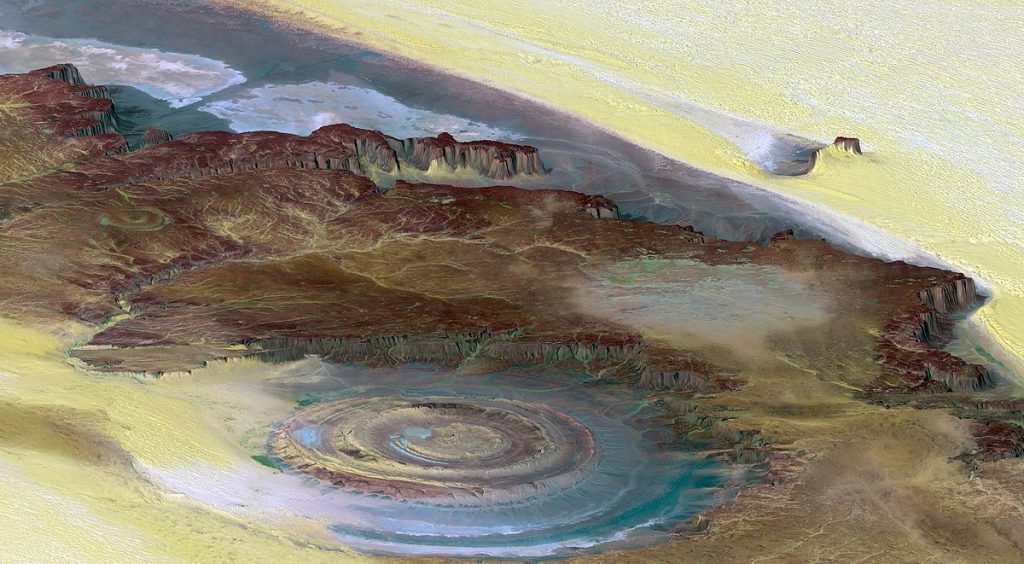

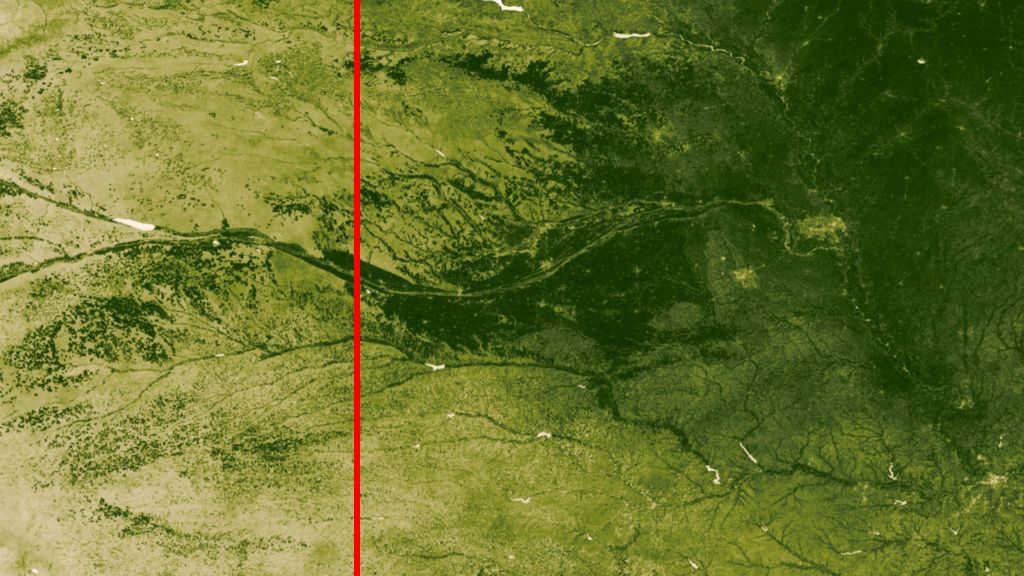

You can also see the line from outer space. I’ve marked the 100th (approximately) on this satellite photo of Nebraska. The landscape is deep green to the east though not uniform.

Nowadays the 100th is no longer the rainfall divide.

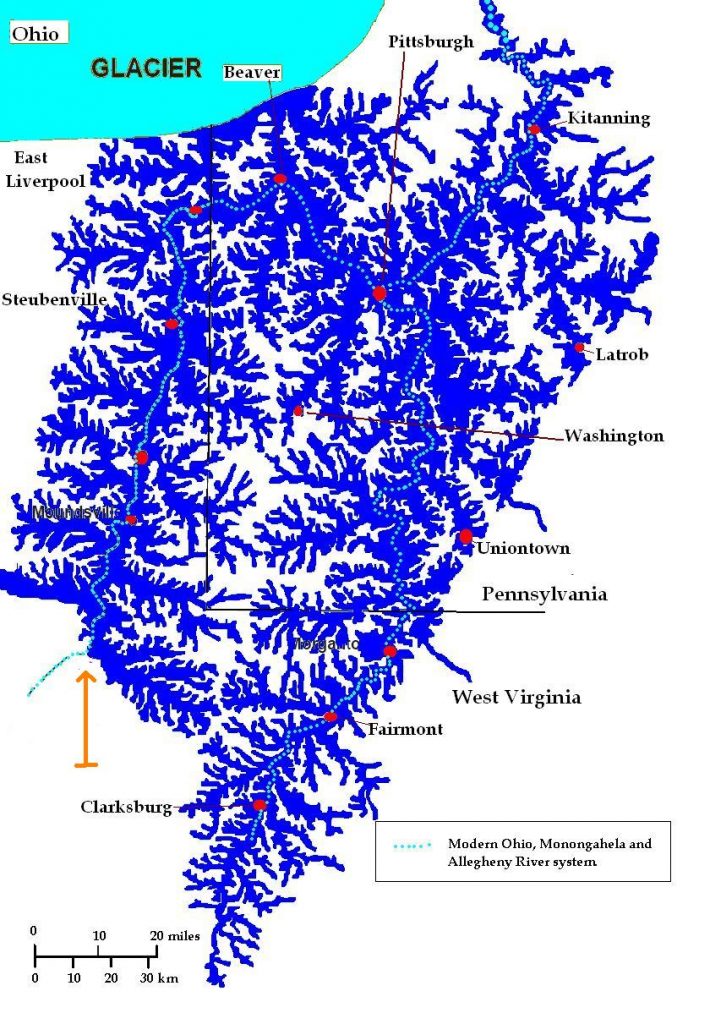

A study by Columbia University meteorologists found that the aridity line has shifted 140 miles east and is now statistically located at the 98th meridian. Climate change will move it even further as warming evaporates moisture in the northern plains and alters rainfall in the south.

In a hundred years the aridity mark may be firmly inside Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri. Aridity decreases the amount of agriculture and will probably change the population. People choose to live where there’s water.

John Wesley Powell’s “100th meridian” is moving east.

This article was inspired by Yale Climate Connections. Read more here in Yale Environment 360, 11 April 2018.

(photos from USDA, USFS and Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)