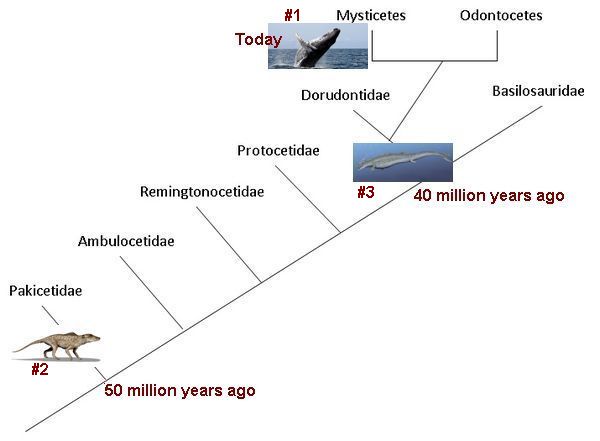

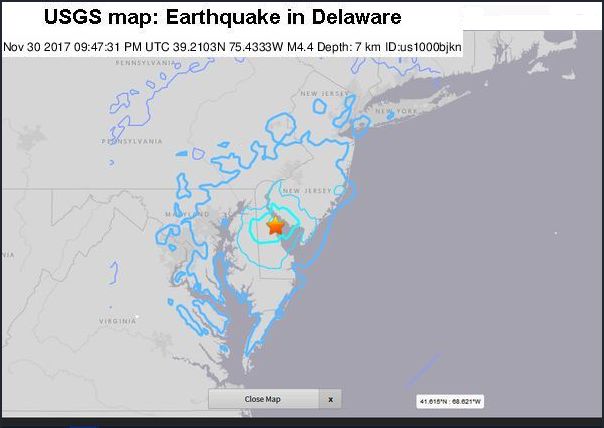

Two weeks ago I read in The Guardian that big, damaging earthquakes could increase in 2018 because Earth’s rotation has slowed slightly. Then yesterday afternoon there was an earthquake at Bombay Hook, Delaware, a place where earthquakes are rare. Are the two related?

In a study published last summer in Geophysical Research Letters, geophysicists Rebecca Bendick and Roger Bilham examined a century of data on major earthquakes (7.0 and above) looking for patterns that might indicate what causes them. They found that there are indeed periods of increased seismic activity when there are up to 20 major earthquakes per year instead of 8 to 10.

They then looked for Earth attributes that fluctuate on a similar time scale. Nothing fit until they found a match with the periodic slowing of Earth’s rotation.

Earth’s rotation slows very slightly — only a millisecond — about every three decades. It’s so slight that you need an atomic clock to notice it, but Earth’s crust appears to notice as well. About five years after rotation enters a slow cycle, there are more frequent major earthquakes around the world.

2018 is five years after Earth entered a slow-rotation period so perhaps there will be more intense earthquakes next year. We’ll have to wait and see.

Meanwhile, what does this finding have to do with the mild 4.1 earthquake at Bombay Hook yesterday? Maybe nothing. But I wonder about it because earthquakes are so rare in Delaware.

Read more about The real science behind the unreal predictions of major earthquakes in 2018 and news of the Delaware earthquake in the Washington Post.

(USGS map of 30 Nov 2017 earthquake centered at Bombay Hook, Delaware; click on the image to see the original)