28 October 2014

Ancient birds have a new family tree.

In a report last month in Current Biology researchers at University of Edinburgh and Swarthmore College analyzed 850 body features of 150 dinosaurs, then used statistical analysis to assemble a detailed family tree from dinosaurs to birds.

Interestingly, they found that the evolution of bird characteristics in dinosaurs was very gradual and non-linear. Features like feathers, wings and wishbones appeared in many species over tens of millions of years so there is no “missing link” dinosaur line to the first bird.

“This process was so gradual that if you traveled back in time to the Jurassic, you’d find that the earliest birds looked indistinguishable from many other dinosaurs,” said Swarthmore statistician Stephen Wang.

And then, 150 million years ago the bird skeleton came together and bang! there was an explosion in species from the one-of-a-kind hoatzin to more than 360 species of hummingbirds. According to Science Daily, this explosion “supports a controversial theory proposed in the 1940s that the emergence of new body shapes in groups of species could result in a surge in their evolution.”

Most kids go through a dinosaur-loving phase. Some of us fall in love with birds and never come out of it.

Read more here in Science Daily about the family tree.

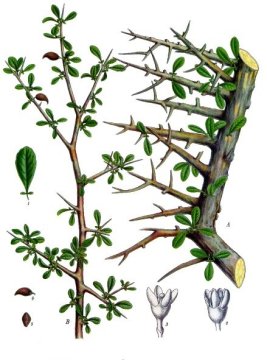

(diagram by Stephen L. Brusatte, University of Edinburgh. Click on the image to see the original.)