As usual, winter is a slow time for observing nature so my blog ideas are pretty thin. However, your encouragement on my Bird Anatomy series (20 Nov 2009 to 25 Feb 2011) has inspired me.

This Friday I’m going begin a new series called Tenth Page.

Though it’s loosely based on bird anatomy, Tenth Page is named for its subject matter. My rule is that I must open Frank B. Gill’s Ornithology at a page number evenly divisible by 10. Whatever is on that page will be fodder for a blog.

I’ve already checked all the tenth pages in my copy of the book and discovered that there are 3 blanks in the #10-series. Aha! Those will be wildcard subjects in which I can pick any old page I please.

And I won’t be predictable. That would be boring. Not 10, 20, 30 for me! To keep myself interested I’m more likely to dip in at random and choose a tenth page that inspires me.

As a result, you won’t be able to guess my subject by reading the book — and neither will I.

Stay tuned for Tenth Page, coming this Friday.

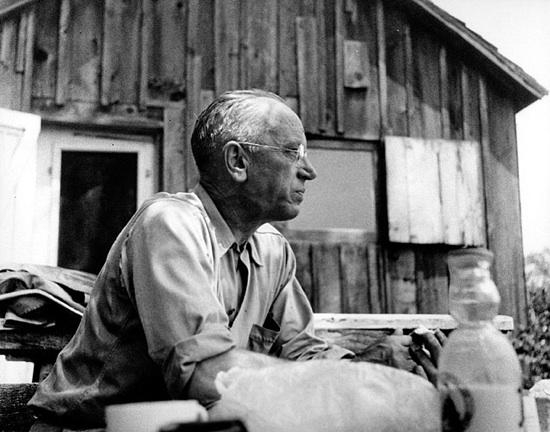

(photo by See-ming Lee via Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original)

p.s. The photo above has a series of its own. Taken by See-ming Lee at Vinegar Hill, New York, NY on 30 Dec 2007, it’s been posted to Wikimedia Commons for use in a series of blogs. Click on the image to see the original photo and the list of blogs that have used it. (Mine is there too.) Pretty cool!

p.p.s. On the Bird-thday blog Peter and Stephen suggested I write about bird calls. Be watching for bird calls sprinkled throughout the year.