22 April 2023

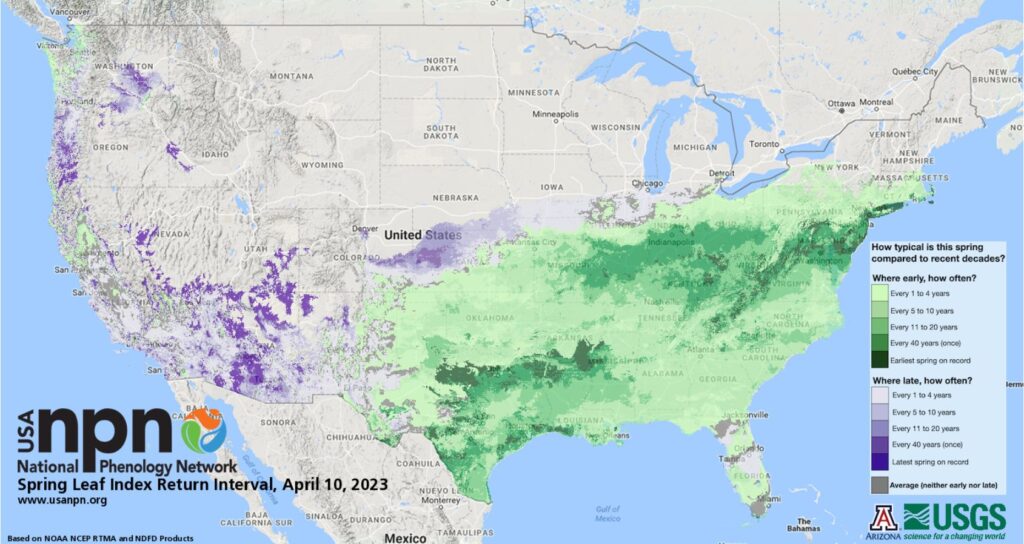

This week in Pittsburgh began 15 degrees above normal, dipped to freezing (10 degrees below normal), then soared back into the 80s. The flowers and leaves coped.

On Saturday 15 April I visited Harrison Hills Park and found busy insects pollinating Virginia bluebells, golden ragwort, spring beauties and garlic mustard.

Garlic mustard is in bloom everywhere right now but I rarely take a picture of it.

On Monday 17 April at Schenley Park, jetbead, greater celandine, and common blue violets were in bloom.

The poison ivy leaves were small on Monday but are much larger now.

By yesterday, 21 April, the redbud was seriously leafing out in Schenley.

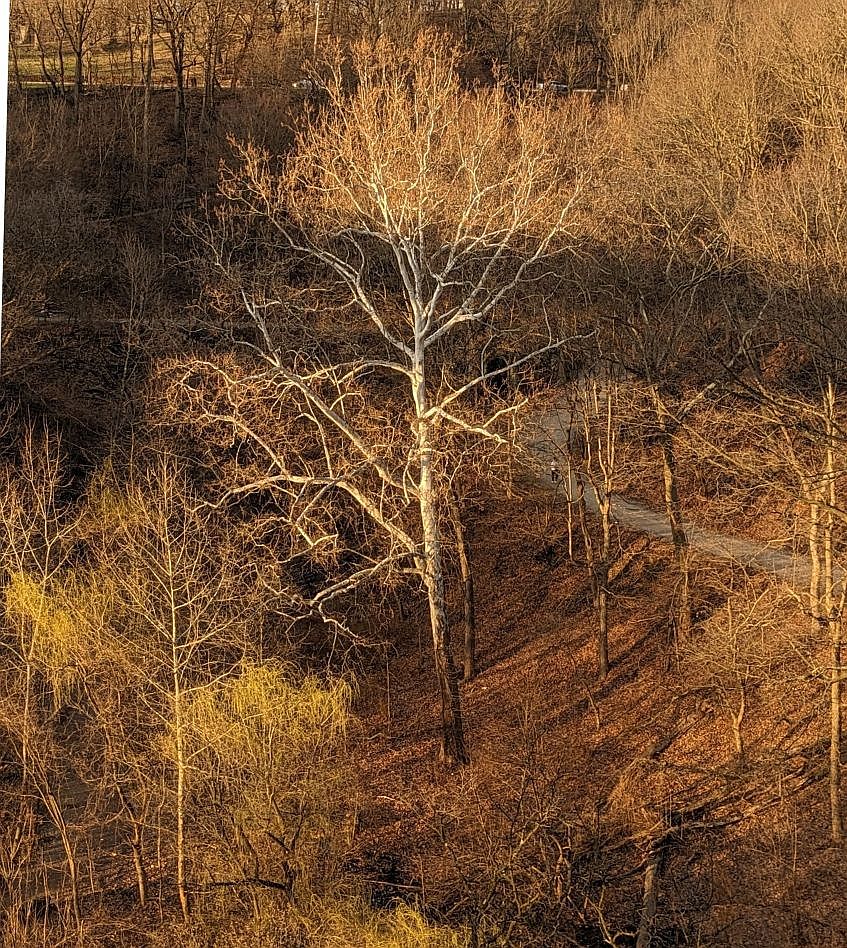

These two photos show Schenley’s leafout progress: The first below is a yellow buckeye near Anderson Playground on 17 April. The second is the same yellow buckeye 4 days later! It’s hard to see Panther Hollow Lake through the trees.

New birds! Yesterday I saw my first of year house wrens and chimney swifts (my Schenley eBird checklist here). Today I’ll dodge the raindrops to find the wood thrush reported by friends near Circuit Drive / Serpentine Road.

Happy Earth Day!

(photos by Kate St. John)