17 March 2025

Happy St. Patrick’s Day!

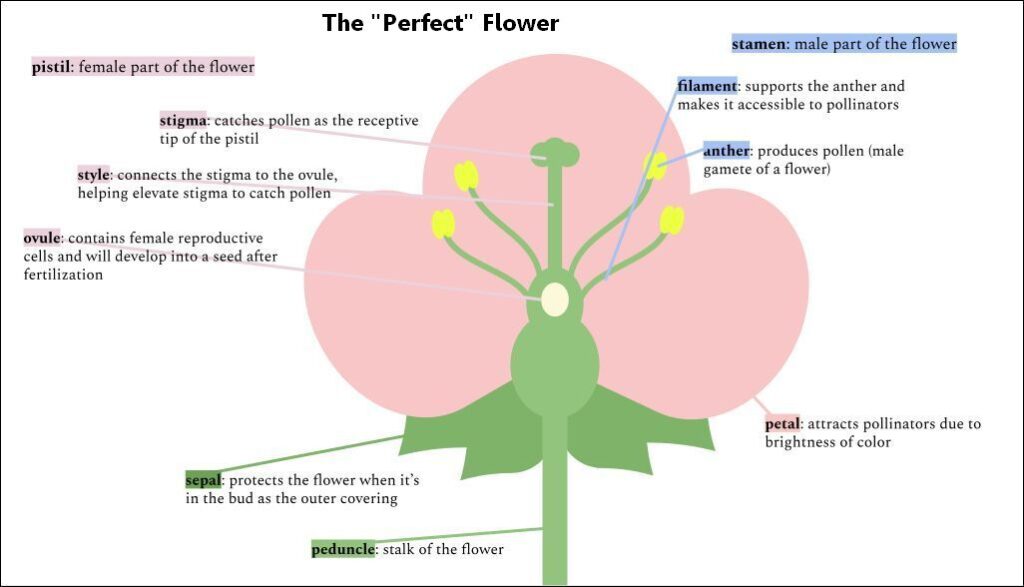

St. Patrick’s and Ireland’s shamrock symbol is a leaf cluster of either lesser clover or white clover. We don’t see much lesser clover (Trifolium dubium) in the U.S. but we used to have lots of white clover. When I was a child our lawns were a mixture of grass and white clover (Trifolium repens).

The mixture worked well because clover sets nitrogen in its roots and naturally fertilizes the grass. As kids we used to search for lucky 4-leaf clovers in the yard.

But times changed. People didn’t want weeds in the lawn and the easiest way to remove them was to spread weed killer that targeted broadleaf plants. Clover is a broadleaf so it died and fertilizer had to be added to the chemical mix.

These neighboring lawns in New Jersey show both types of lawn treatments. At top is a chemically treated lawn without broadleaf plants. At bottom is an old fashioned grass-and-clover mix. If you can’t see the dividing line, click on the photo to see the divide.

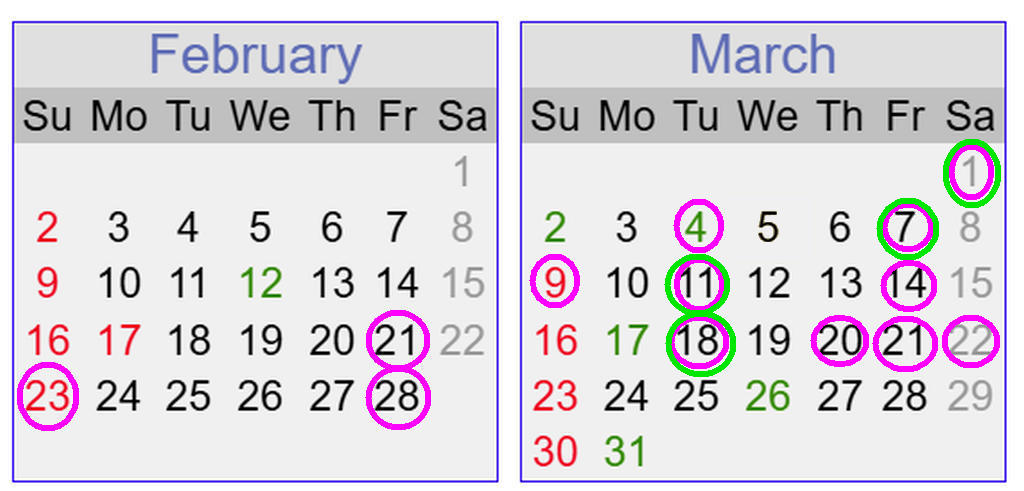

Chances are you’ll have to search for lucky 4-leaf clovers in a photo instead of on the lawn. How many are in this photo? (Click on it to see a larger version.)

p.s. False Shamrock: The “shamrock” plant often sold around St. Patrick’s Day is not related to clover. “False shamrock” or “purple shamrock” (Oxalis triangularis) is native to Brazil.