25 March 2020:

Around the world, more and more of us are under Stay At Home orders to stop the spread of COVID-19. Yesterday Governor Wolf announced that eight PA counties — 45% of Pennsylvanians — must Stay At Home through 6 April. Fortunately residents are permitted to “engage in outdoor activity, such as walking, hiking or running if they maintain social distancing” — i.e. stay at least 6 feet apart.

So I’ve been going outdoors alone … especially when the weather is drizzly, cold or gray because no one else is out there. I’ve seen lots of birds including red-winged blackbirds, hundreds of American robins, eastern phoebes, a brown-headed cowbird, a golden-crowned kinglet and a merlin(!) in Schenley Park.

I’ve also photographed some signs of spring, 18-24 March 2020. Flowers are blooming in Greenfield’s neighborhood gardens, above and below.

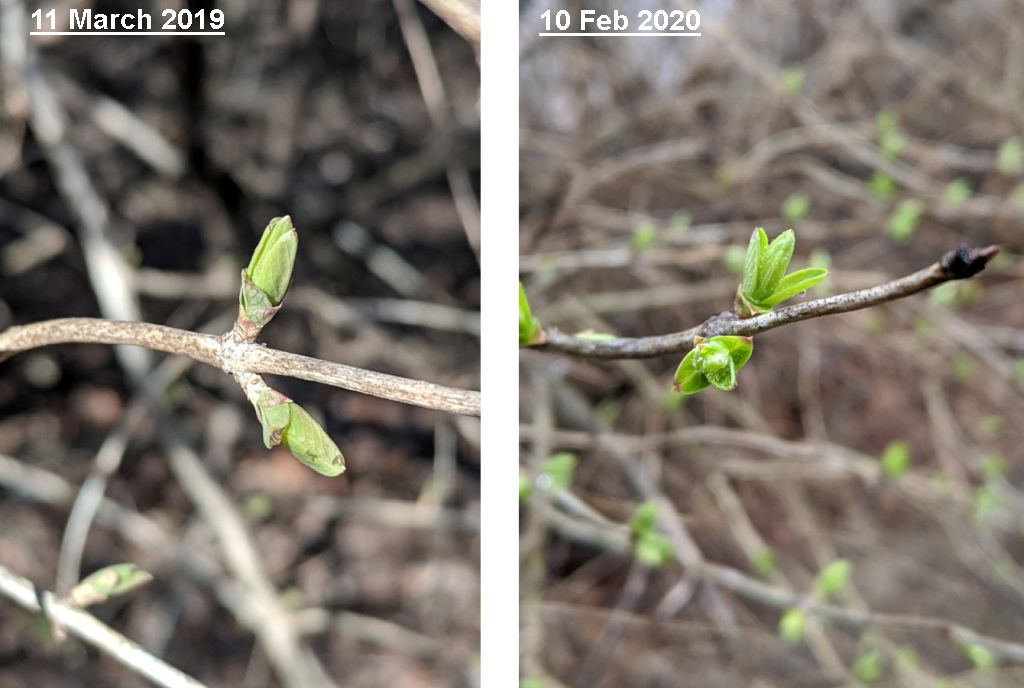

The earliest trees are beginning to leaf out including the bottlebrush buckeyes (Aesculus parviflora) in Schenley Park.

Cornelian cherry trees (Cornus mas) are in bloom at Schenley. Photos of the whole tree and a blossom closeup.

Yet the rest of the forest is still quite brown. The smaller American beech trees (Fagus grandifolia) stand out with dry pale leaves. Photo from afar and a close-up.

Getting outdoors is not cancelled.

Stay safe.

(photos by Kate St. John)