Except for a 10 degree cold snap in the last 24 hours, we’re having an early Spring.

So far this year temperatures in Pittsburgh have been 10-34 degrees above normal a third of the time. January 11 was 34 degrees above normal at 71 degrees F.

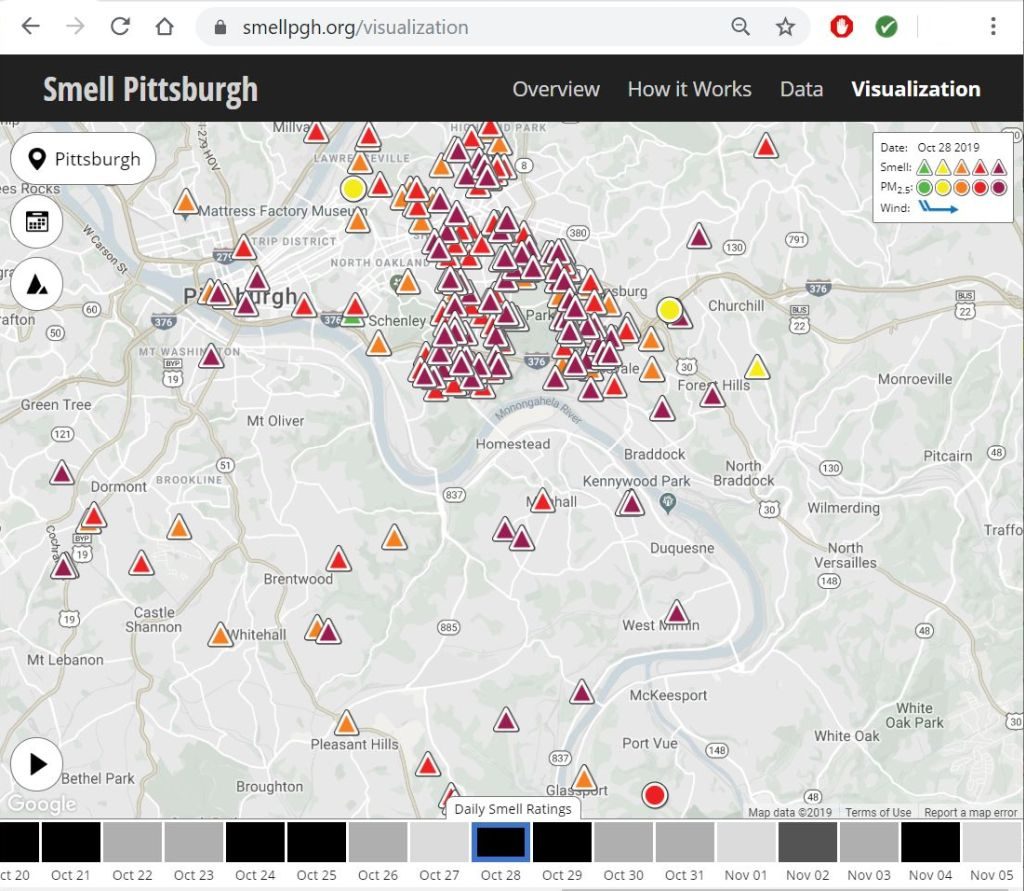

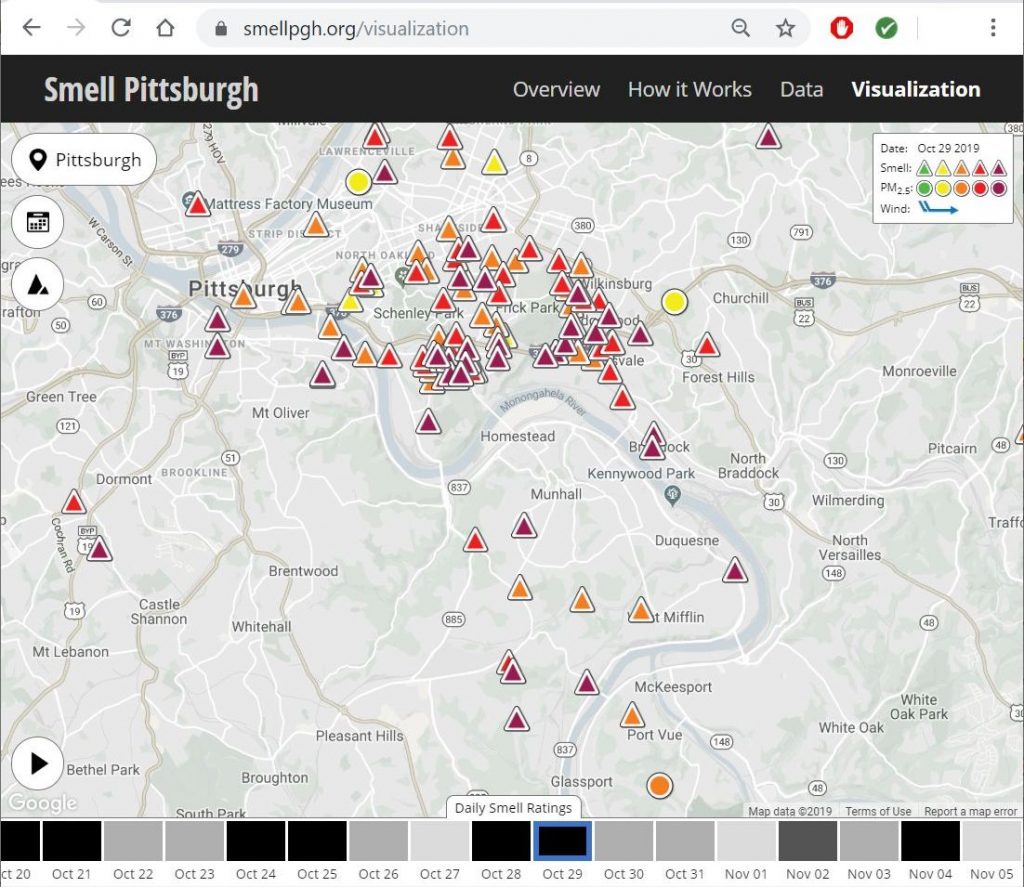

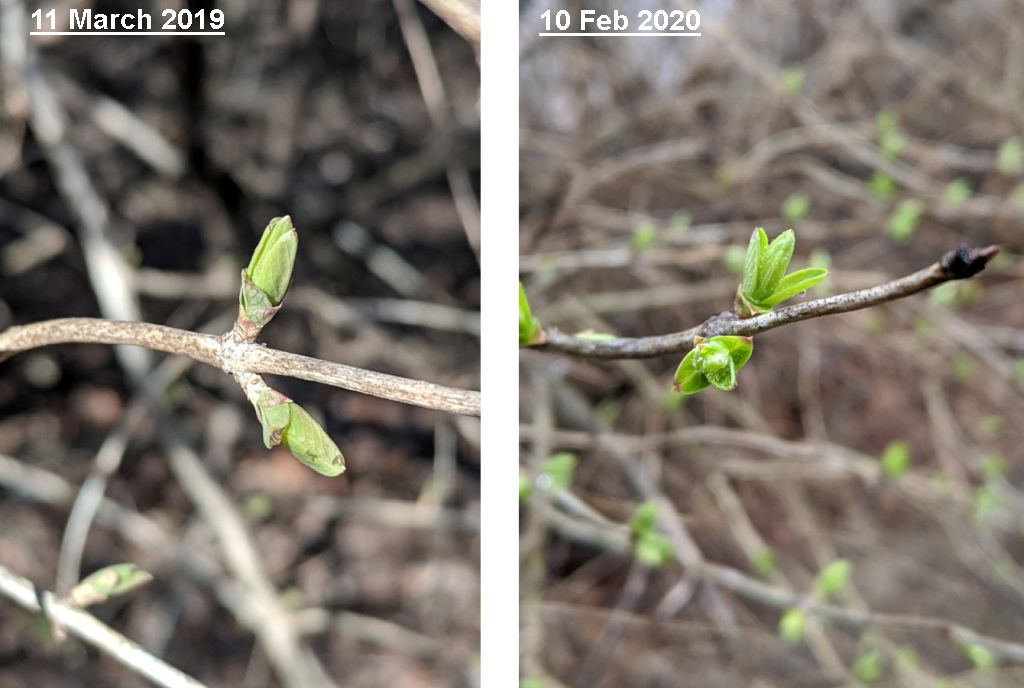

Honeysuckle bushes responded by leafing out. Last Monday (10 February 2020) I found open honeysuckle buds in my neighborhood. I took a similar photo last year on 11 March 2019 but it was whole month later and the buds were not as open.

According to the USA National Phenology Network, Spring is three weeks ahead of schedule in the southeastern US:

Spring leaf out has arrived in the Southeast, over three weeks earlier than a long-term average (1981-2010) in some locations. Charlottesville, VA is 24 days early, Knoxville, TN is 20 days early, and Nashville, TN is 18 days early.

— Status of Spring USANPN.org

Here’s what it looks like on the map as of 14 February 2020.

Despite the cold, today will warm to almost 40 degrees in Pittsburgh and to 52 by Tuesday. I think we’ll still have an early Spring.

(photos by Kate St. John, map from USANPN.org)