August is the perfect time to watch pokeweed change from flower to fruit.

Read about its metamorphosis in this vintage article: Pokeweed In Stages.

(photo by Kate St. John)

August is the perfect time to watch pokeweed change from flower to fruit.

Read about its metamorphosis in this vintage article: Pokeweed In Stages.

(photo by Kate St. John)

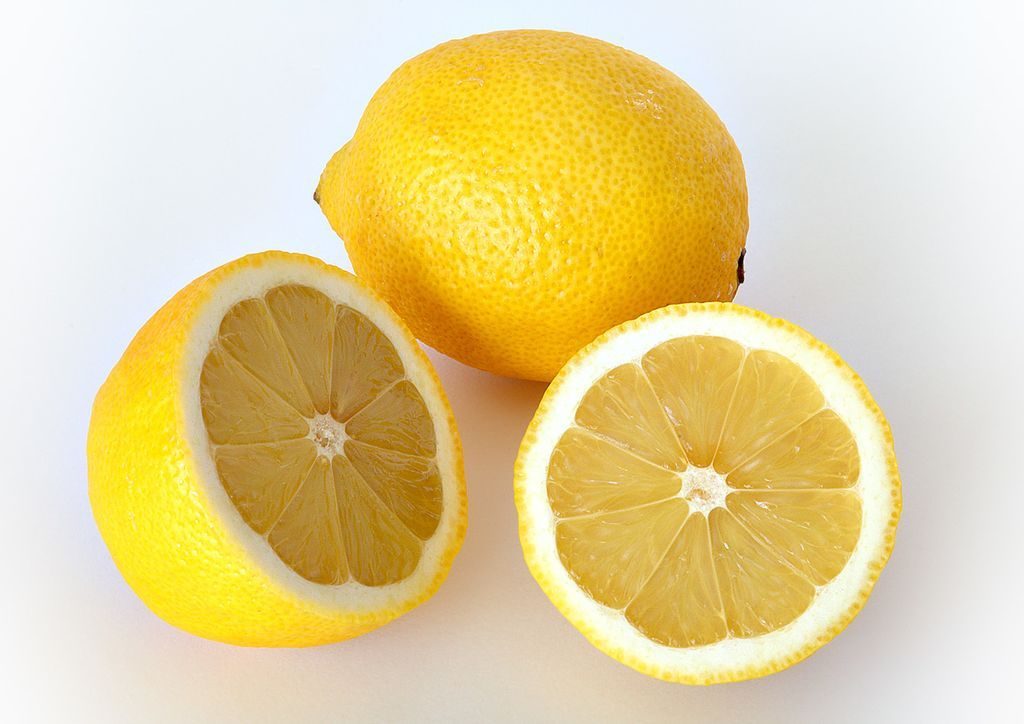

What do red petunias and lemons have in common?

They share a cell mechanism that regulates acid.

Ronald Koes at Univ. of Amsterdam discovered that red petunias have a vacuole proton pump that concentrates acid in their flower cells. Without the acid, those petunias would be blue.

He then examined DNA in a variety of citrus fruits, from sweet to very sour, and found that the sour ones have the same cell mechanism.

This discovery gives fruit and flower breeders a DNA marker for achieving desired colors and flavors.

Are red petunia flowers sour? … I’m not going to taste them to find out.

Read more about this discovery in Science Magazine.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons)

Tiny spines line every stem of this flowering plant as its yellow-green flowers reach for the camera.

Can you guess what plant this is?

Hint: Stay away from it!

In a few weeks this plant will be very aggravating. Those tiny green balls are solidly attached to the stems right now but soon they’ll dry out and grab onto your clothes and your dog if you brush past the plant. They’re the fruits of Virginia stickseed (Hackelia virginiana).

Virginia stickseed is so inconspicuous in bloom that we barely notice it at this stage.

The flowers are tiny …

When fertilized they become small burs made of four nutlets facing each other. The outer surface is like velcro.

To give you an idea of their size, I pulled some fruits off the stem. It was hard to detach them because they haven’t dried out yet in early August.

Just wait until they turn brown!

p.s. There’s another less common native plant called small flowered agrimony with a similar fruit. Read more about it in this vintage blog: Slightly Aggravating.

(flowering plant photo from Wikimedia Commons; click on the caption to see the original. All other photos by Kate St. John)

Perhaps you already know this but it was news to me: Cinnamon repels ants.

Cinnamon comes from the dried inner bark of a tropical evergreen, the cinnamon tree (Cinnamomum sp.). Ants would eat these trees alive if they could but the cinnamon genus evolved a very effective defense: two chemicals, Cinnamaldehyde and Cinnamyl alcohol, that are toxic to ants. Ants stay away from cinnamon.

In this 9-minute video, the guy from You Can Science It shows that even swarming, warring ants will drop what they’re doing when confronted with cinnamon. He theorizes that it changes their messaging from “Kill the other colony” to “Oh no! It’s cinnamon!” (video begins where he starts discussing cinnamon. Click here for the full video.)

Yes, cinnamon repels ants but it has to be fresh and you have to use a lot of it.

Read more about this experiment and the research behind it in this 2015 blog post at You Can Science It.

(photo and illustration from Wikimedia Commons, video from You Can Science It on YouTube)

29 July 2019

Yesterday in Schenley Park, as we saw several white-tailed deer quite close to us, I remarked that the number of deer in Schenley is too high for the park’s habitat. How can you tell if there are too many deer in your neighborhood? Take a look at the arborvitae.

Many species of arborvitae (Thuja spp.) are planted as privacy hedges including our native Thuja occidentalis or northern whitecedar.

In the wild and in our yards Thuja trees are a favorite food of white-tailed deer. They browse it from the ground up to the height of their outstretched necks.

When the number of deer is in balance with the landscape, arborvitae have a normal tapered shape. You’d never notice that the deer are eating them.

When there are more deer than the landscape can handle, their browsing is intense. The trees are cropped close to the trunk — even down to the bark — because the plants can’t replace their branches fast enough.

If your arborvitae trees look like the row shown at top, there are too many deer in your neighborhood, the landscape is out of balance. “Too many” can happen fast. Deer can double their population in just two to three years.

I photographed that row of damaged trees just six blocks from my house. Yes, my city neighborhood has too many deer now. We could protect our trees with netting as described in this video. Or we could give up and never plant arborvitae again.

p.s. There are too many deer everywhere in the eastern U.S., even in the forest. Read more here.

(photo by Kate St. John)

Puzzled by these red berries?

They’re the fruit of Amur or bush honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii) that looked like this in June.

The flowers are white when they bloom. They turn yellow when fertilized.

Red fruits from white flowers.

(photos by Kate St. John)

Last week I saw two caterpillars and a butterfly that teased me: Who am I?

1. While taking closeups of Japanese snowball fruit (Viburnum plicatum) I saw the tiny green insect above looking at me from the corner of a leaf.

iNaturalist suggests he’s a moth in the genus Isa, a slug moth. However none of the photos show a caterpillar with a tiny black eye. He seems to be saying, “Who am I?” UPDATE, 24 July 2019: Monica Miller says he’s a planthopper, one of many confusing species.

2. On Lower Riverview Trail I paused where lots of tiny caterpillars were dropping to the ground on thin silk filaments. Were they a type of tussock moth? “Who am I?” UPDATE, 24 July 2019: Monica Miller confirmed my guess that these are hickory tussock moth caterpillars.

And in Schenley Park on the Greenfield Bridge I found an emperor. A hackberry emperor? A tawny emperor (Asterocampa clyton clyton). Thanks to Bob Machesney for the ID!

This week I noticed for the very first time that there are tiny knobbed hairs on moth mullein stems, sepals and fruit capsules.

Moth mullein (Verbascum blattaria) is a biennial plant native to Eurasia and North Africa that’s now naturalized in North America. It blooms here from June to October.

The earliest flowers have already produced fruit by July. Each fruit is the swollen ovary of one of these flowers.

Eventually, the stem and seed capsules dry out …

… but they still have those tiny hairs. (Click here to see a closeup.)

(photos by Kate St. John. Except: dried seed pods from Wikimedia Commons; click on the caption to see the original.)

Last month we found chocolate lilies and other delightful wildflowers while on PIB‘s Alaska birding tour. Here are the best of them, mostly found at Turnagain Pass Rest Area on 18 June 2019. Please leave a comment to help me identify the ones I’ve labeled “mystery” flowers and correct any I’ve misidentified. Thanks!

At top, the chocolate lily (Fritillaria camschatcensis) is a gorgeous small flower that resembles a Canada lily (Lilium canadense) except that it’s the color of chocolate. What a treat!

Below, clasping twisted-stalk (Streptopus amplexifolius) has delicate bell-shaped yellow flowers that hang under the leaves. They remind me of Solomon’s seal.

Nootka lupine (Lupinus nootkatensis) starts blue, becomes white at the tip.

Devil’s club (Oplopanax horridum) is covered in spines that are hard to remove if they get in your skin. Don’t touch!

Woolly geranium (Geranium erianthum) looks like Pennsylvania’s wild geranium. The flowers and leaves are larger, though.

We saw liverleaf wintergreen (Pyrola asarifolia) in Seward.

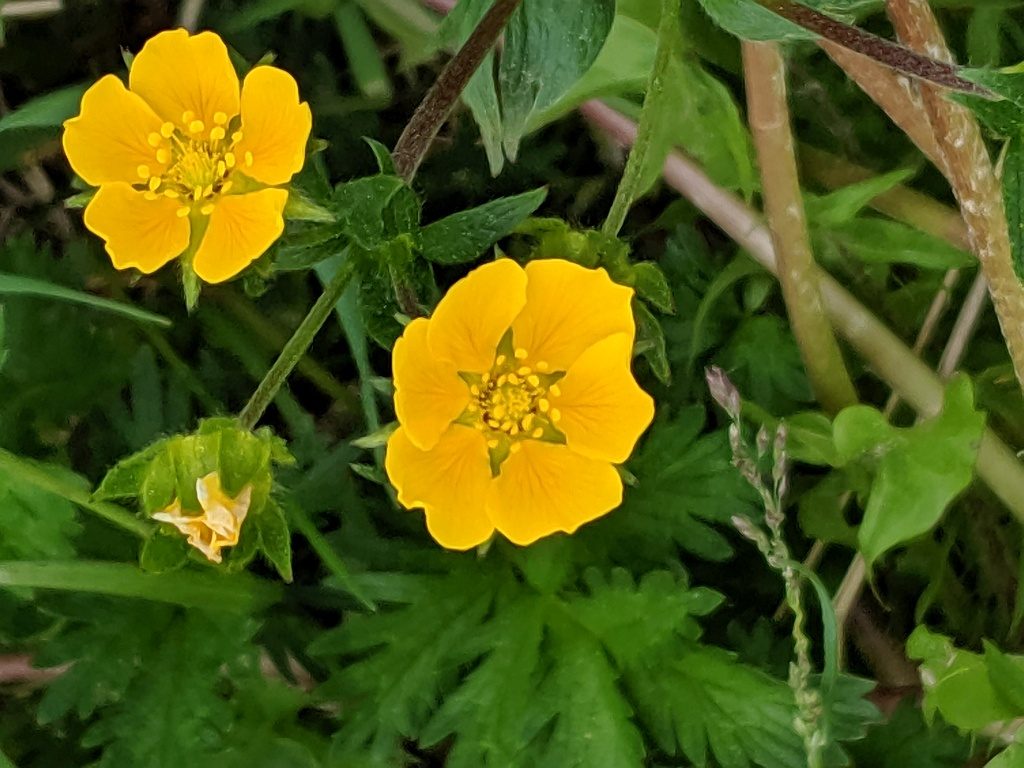

What is the yellow flower shown below? It looks like a cinquefoil to me but the leaves are so big. (The flower is about the size of the first joint of my thumb.)

I believe this is salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis). Am I right?

Threeleaf foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), found in Seward.

I couldn’t identify this flower at first, but thanks to Janet Campagna’s comment I think these are yellow marsh marigold (Caltha palustris), seen at Turnagain Pass Rest Area, 18 June 2019.

And finally, dwarf fireweed (Chamaenerion latifolium) was easy to find along the Teller Road northwest of Nome.

Please let me know if I’ve misidentified any of these. The solo yellow flower, 7th photo, remains a mystery.

(photos by Kate St. John, all of them taken with my Pixel 3 cellphone)