This spiny 2-inch-long seed pod is all that’s left of a Wild Cucumber (Echinocystis lobata) fruit.

Click here to see what it looked like last summer.

(photo by Kate St. John)

This spiny 2-inch-long seed pod is all that’s left of a Wild Cucumber (Echinocystis lobata) fruit.

Click here to see what it looked like last summer.

(photo by Kate St. John)

30 April 2014

While it feels like it’s been raining forever, last weekend’s weather was sunny and so were the flowers. Here’s a selection I found at Raccoon Creek Wildflower Reserve and Friendship Hill National Historic Site on Saturday and Sunday.

Above, a very close look at Great Chickweed (Stellaria pubera), also called Star Chickweed. The flower is only 1/2″ across and it has only five petals but they’re so deeply cleft that they look like ten.

Below, inch-long Virginia bluebells (Mertensia virginica) in bloom at Raccoon Wildflower Reserve. I love how they change color as they open.

Toad Trillium or Toadshade (Trillium sessile) is rarely seen from this angle because the plant is only four inches tall. (I got muddy taking this picture.) The dark, closed petals look boring from above but graceful from the side. Perhaps they open like this so the pollen can disperse more easily. It’s dusting the leaf at front left.

Today’s April showers will bring May flowers. It’s hard to believe that May begins tomorrow.

(photos by Kate St. John)

Dianne Machesney found this Halberd-leaved Violet blooming at the Cucumber Falls Trail in Ohiopyle State Park last week.

A halberd is a long pole with a battle ax; the ax always has a hook on the back end. It was a popular weapon in the 14th and 15th centuries.

What do you think? Is this a “halberd” leaf?

(photo by Dianne Machesney)

19 April 2014

The mid-week freeze damaged flowers on our northern magnolia trees. Above, a bruised Star magnolia, below, a very brown Saucer magnolia, both in Oakland.

Northern magnolias are non-native trees from Asia, specially cultivated for their early blooms, so their timing isn’t right for our mid-April cold snaps.

Our native plants had no problem because the freeze occurred within the normal span of our last killing frost.

Yesterday Dianne Machesney found beautiful flowers blooming at Cedar Creek Park in Westmoreland County, some of them new since I was there last weekend.

Harbinger-of-spring’s tiny flowers are quite hardy. This plant is often the first to bloom.

Twinleaf is new this week because its internal clock told it to wait. The flower resembles bloodroot but the leaves are quite different. (Click here for a view of its twin leaves.)

The natives bounce back fast.

(northern magnolia photos by Kate St. John. Flower photos by Dianne Machesney)

15 April 2014

During the past three days we had a burst of blooms in Pittsburgh. Between Saturday morning’s foggy low and Sunday’s high of 82F the landscape transformed from incipient buds to gorgeous flowers. (Today will be different, but more on that later.)

On Saturday, 12 April 2014, I found bloodroot at its peak at Cedar Creek Park in Westmoreland County (above) as well as spring beauties…

trout lilies…

and hepatica.

This morning the temperature is dropping fast. It was 65oF at 5:00am and has already fallen to 47oF as I write.

Tomorrow’s prediction: 21oF at dawn. This will surely ruin the flowers.

It was fun while it lasted.

(photos by Kate St. John)

At last the crocuses are (or rather… were) blooming in Pittsburgh, though not in my yard.

Yesterday was a sunny and breezy day with a high of 50F. I took a long walk in Schenley Park and found nothing blooming except a small selection of snowdrops and crocuses at Phipps Conservatory’s outdoor garden.

Today it has already snowed a little, tonight will be 15F and the cold will continue through Tuesday so these flowers won’t last.

If you want to see spring in all its glory visit the Spring Flower Show, indoors at Phipps Conservatory. Theirs are the only flowers that have put in more than a brief appearance.

(photo by Kate St. John)

16 January 2014

On my way to somewhere else I found…

It’s hard to believe these mushrooms represent the largest living organism but they’re the outward and visible sign of a subterranean and under-bark network.

The network can be quite large, as described here on Wikipedia: “The largest living fungus may be a honey fungus of the species Armillaria ostoyae [now called Armillaria solidipes]. A mushroom of this type in the Malheur National Forest in the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon was found to be the largest fungal colony in the world, spanning 8.9 km² (2,200 acres) [and] estimated to be 2,400 years old. … If this colony is considered a single organism, then it is the largest known organism in the world by area.”

And so it was named the “Humongous Fungus.“

There are many species of Armillaria, all with dark shoestring-like rhizomorphs that grow through the soil or under bark and white mycelial fans which spread under bark via root contacts and root grafts. Here’s what they look like: rhizomorphs on the left, mycelia on the right. (For a sense of scale, these are tree trunks)

Sometimes the mycelia are luminescent and cause foxfire!

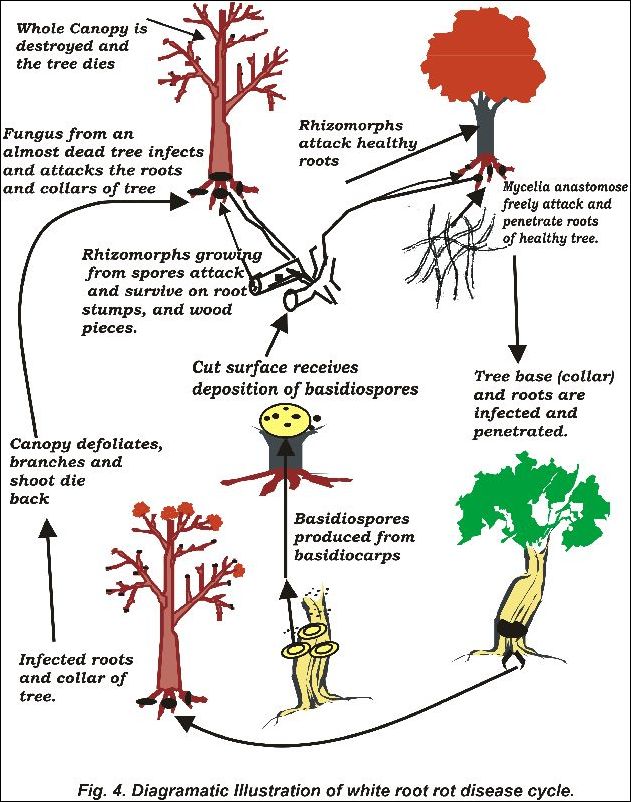

Fascinating as their huge size may be, Armillaria spreads widely, infects many trees and can either kill them outright or be a contributing factor to their demise. This diagram shows how it cycles through the forest.

I have seen Armillaria in Schenley Park without realizing what it was: rhizomorphs, mycelia and mushrooms.

So now I understand how a live tree can just fall over when infected by Armillaria root rot.

(photo credits: mushrooms by Walter J. Pilsak via Wikimedia Commons (click on the image to see the original). Rhizomorphs and dead tree on grass by Joseph O’Brien, USDA Forest Service via Bugwood.org. White mycelial fan by Borys M. Tkacz, USDA Forest Service via Bugwood.org)

‘Tis the season for kissing under the mistletoe but this genus is too small for the purpose.

Mistletoes are parasitic plants in the sandalwood family. The ones we associate with kissing, Phoradendron leucarpum and Viscum album, are evergreen plants that parasitize oak and apple trees. In winter they look like green balls in the bare trees. Click here for a photo and description.

Dwarf mistletoe, on the other hand, is amazingly small. Arceuthobium’s 42 dioecious species parasitize only conifers. The female plant of American dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium americanum) is shown above, the male below. Notice the tiny size of the plant relative to the pine needles.

Dwarf mistletoe begins its life as a seed that lands on a tree branch, then germinates and grows beneath the bark, sucking water and minerals. It rarely kills the tree but the tree fights back by developing witches’ brooms or losing branches as shown on this lodgepole pine. Foresters hate dwarf misletoe.

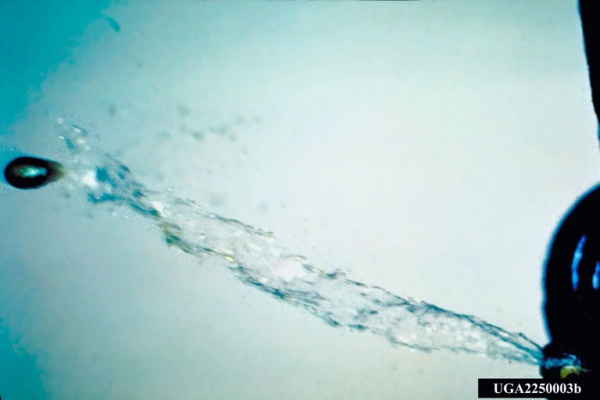

Many mistletoes depend on birds to spread their seeds, but dwarf mistletoe takes matters into its own hands. During the 18 months of seed maturation, water pressure builds up in the seed capsule until it finally bursts out, traveling at almost 50 mph … like this!

Pow! The size of a grain of rice, it can travel 65 feet!

Tiny but powerful. Watch out below!

(all photos are American dwarf mistletoe, Arceuthobium americanum, from Bugwood.org: 1241494 by John W. Schwandt USDA Forest Service, 2141082 by Brytten Steed USDA Forest Service, 2250003 by Frank Hawksworth USDA Forest Service, 5367211 by Mike Schomaker Colorado State Forest Service)

The colors of a Merry Christmas…

Pyracantha after a rare snowfall in Nags Head, North Carolina, February 2006 by Bob Muller.

(photo by Bob Muller (bobxnc), Creative Commons license via Flickr)

Though Christmas wreaths are a northern tradition this one at Phipps Conservatory is made of bromeliads from the American tropics.

After the weather turns cold tomorrow you might be wishing you were somewhere warm. If you’re in Pittsburgh you can warm up at the Winter Flower Show at Phipps Conservatory. They’re all decked out for the holidays through January 12.

I love to bask in the humid warmth with tropical plants when its cold outside. I can almost believe I’m on vacation.

(bromeliad Christmas wreath at Phipps Conservatory. photo by Dianne Machesney)