Poisonous to us but popular with birds, Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) stands out in the landscape now that the leaves are off the trees.

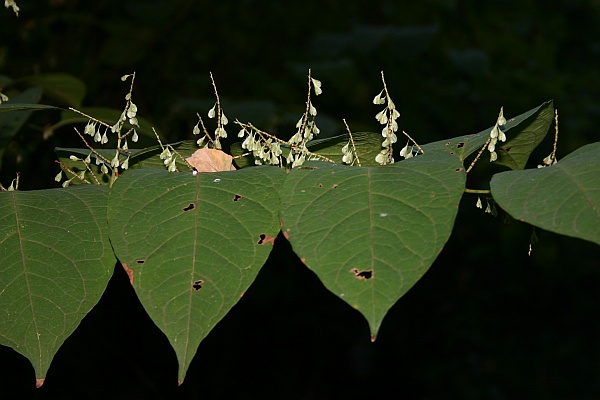

This closeup of the berries shows why we like to use it in floral arrangements. Very beautiful.

But it’s aggressive. Imported in 1879 it grows more easily than American bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) with which it hybridizes. It occurs in nearly every state east of the Mississippi and is listed as invasive from Maine to North Carolina, from Wisconsin to Tennessee.

Watch for small flocks of birds feeding in the woods and you’ll find this vine. Click here to see what it looks like from a distance.

Bitter and sweet: an unruly competitor that’s food for birds.

(photo by Dianne Machesney)