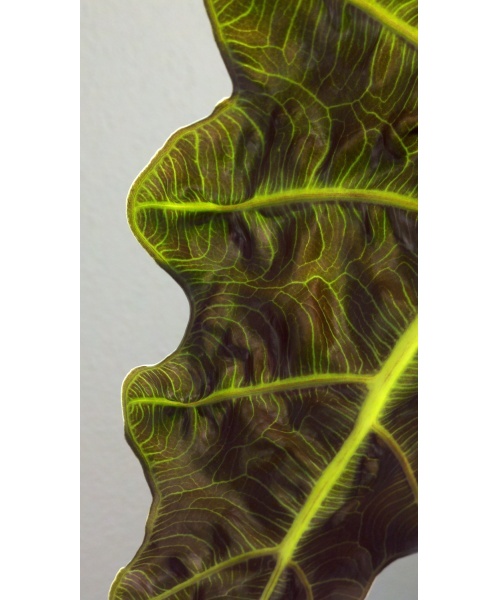

The Christmas tradition of kissing under the mistletoe came to North America with European colonists. Back home they used Viscum album for this purpose. Here they found a very similar native plant, Phoradendron leucarpum, that worked just as well.

Growing up in Pittsburgh I always thought of mistletoe as an exotic import that could only be bought in the store. I never saw it in the wild because we’re just north of its range but it’s quite common in the south, noticeable as balls of greenery in bare trees at this time of year.

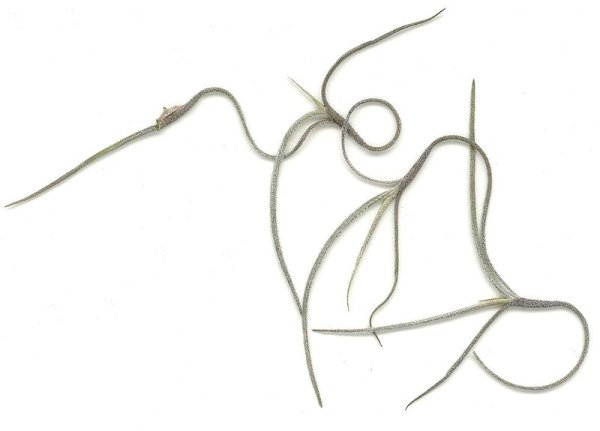

Mistletoe is a hemiparasitic plant that grows on tree branches, sending its roots into the bark. It is partly (hemi) parasitic because it produces its own food through photosynthesis but needs its host for water and minerals. It doesn’t normally kill its host. That would be suicidal. It needs its host to survive.

Like many plants mistletoe relies on birds to spread its seeds but there’s a twist. Birds like to eat mistletoe berries and they don’t digest the seeds but the seed must survive the bird’s gut and stick to a tree branch long enough to germinate. To do this the seeds are coated in a very sticky substance. Birds either avoid swallowing the seeds and wipe their sticky bills on a branch, or they swallow the seed and fly elsewhere to “deposit” it. Favorite perching trees receive more deposits. That’s why you see a lot of mistletoe in some trees but not others.

Some birds are mistletoe specialists. In the desert West, phainopeplas get their water and nutrition from desert mistletoe for much of the year. A phainopepla can eat up to 1,100 mistletoe berries per day.

Though mistletoe’s parasitic nature gave it a bad name, recent studies have shown that animals, birds and habitat are more diverse where mistletoe thrives. It apparently holds the ecosystem together … like a kiss joins a couple.

Have you hung a sprig of mistletoe this year?

(photo of mistletoe in Delaware by Charlie Hickey)