On my way to somewhere else on the Internet I found…

Rubber rabbitbrush (Ericameria nauseosa) is a shrubby perennial in the Aster family native to the arid American West. It’s a hardy plant that thrives in poor conditions, sending down deep roots even in coarse and alkaline soil. I’m sure I’ve seen it in Nevada but it wasn’t blooming at the time.

For most of the year rubber rabbitbrush — also called chamisa or gray rabbitbrush — looks a lot like sagebrush but in the late summer and fall it produces clusters of pungent-smelling yellow flowers that light up the landscape. Pungent is probably a kind word for the smell. Some compare it to the smell of a wet armpit. Bees like it, though.

Its odd name comes from …

- The sap which contains rubber. It was studied as an alternate source of rubber during World War II. The idea didn’t catch on.

- “Rabbitbrush” is forage for deer and antelope but rabbits don’t eat it. Maybe rabbits hide under it.

- The word “nausea” sticks to this plant’s scientific name even after it changed from Chrysothamnus nauseosus to Ericameria nauseosa. Nauseosa might describe its smell.

But what really caught my eye was the fact that in one valley in New Mexico these plants are radioactive.

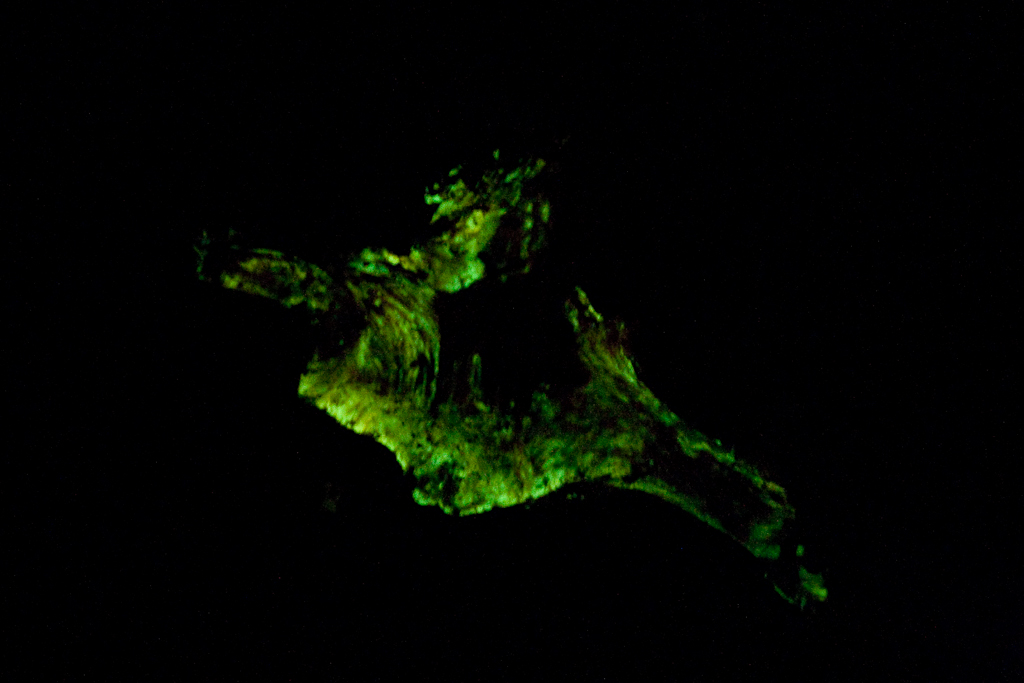

As mentioned above, rubber rabbitbrush will grow in poor soil and send down deep roots. In Bajo Valley near Los Alamos there’s an old nuclear waste dump. Years after the area closed, rubber rabbitbrush grows above it and those particular shrubs are radioactive.

According to Wikipedia, “Their roots reach into a closed nuclear waste treatment area, mistaking strontium [strontium-90] for calcium due to its similar chemical properties. The radioactive shrubs are “indistinguishable from other shrubs without a Geiger counter.”

This happens to humans too. Our bodies mistake strontium for calcium and put it in our bones. It’s good news when treating osteoporosis with non-radioactive strontium but bad news if your water contains radioactive strontium from industrial, mining or Marcellus shale drilling waste.

When in doubt, test your water.

But don’t worry about radioactive bushes. You’d have to go to Bajo Valley, New Mexico to find them.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the caption to see the original.)