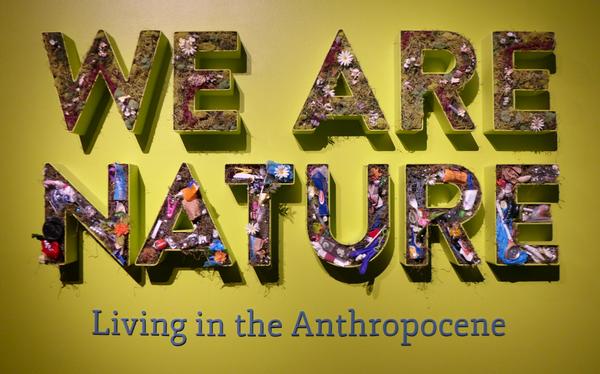

Sometimes it’s hard to imagine that we humans are part of the natural world. We think we are outside of Nature, instead we are intricately entwined. This special exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History shows how we affect Nature and are affected by it.

We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene tells many stories of our impact on Earth by focusing on five areas: pollution, extinction, PostNatural (intentionally altered organisms), climate change, and habitat alteration.

Some of our effects are so common we forget they wouldn’t exist without us. Dogs, for example. They’re in the PostNatural category.

We also tinker with wild things like wolves. The plaque below this animal says:

“A Trickle-Down Effect (Trophic Cascade): Humans eliminated gray wolves from Yellowstone National Park in the 1920s. In 1995, 31 gray wolves were reintroduced to the park from Canada; the wolf population is now considered stable. While some ranchers may not agree, the return of wolves to Yellowstone, coupled with other ecological factors, has had positive effects on biodiversity and the health of the park.”

But most of our effects occur when we aren’t paying attention.

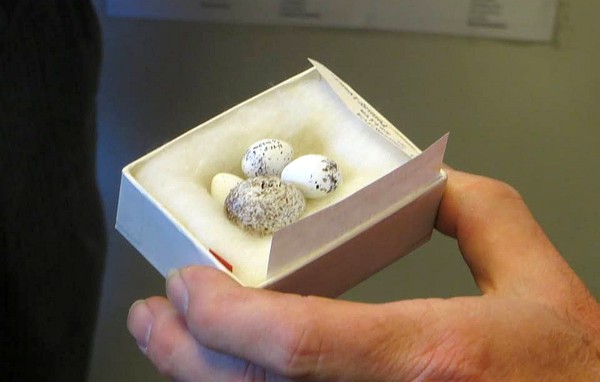

Acid rain is a byproduct of burning coal to generate electricity. We had no idea this made a difference until we noticed that our downwind lakes were becoming acidic. More than a water problem, acid rain makes land snails scarce and causes declines in ovenbird breeding success. An exhibit of tiger snails says:

Tiger Snail + Acid Rain: Acid rain from human pollution harms some of Pennsylvania’s smallest animals: tiger snails. … Museum scientist Tim Pearce found that before 2000, the tiger snail was found in 53 Pennsylvania counties. After 2000, that number was cut by more than half.

There’s one object in the room that’s the perfect emblem of our aimless effect on earth — a shopping cart coated in zebra mussels.

The shopping cart says, “Humans were here.”

- Humans manufactured something not found in nature.

- The cart ended up in one of the Great Lakes through human negligence (it rolled) or purpose (dumped).

- As it lay submerged zebra mussels attached themselves to the cart. Zebra mussels are an invasive species accidentally introduced to the Great Lakes in the 1980s. They got there on the bottoms of boats.

Without humans, nothing about this object would exist.

See more amazing stories of our impact at We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Click here for more information.

p.s. In the Post-Gazette I learned that this is the first exhibition about the Anthropocene in North America. (Go, Pittsburgh!) It will run for a year, include additional programming, and the museum plans to hire a curator of the Anthropocene in January.

(photos by Kate St. John)