5 February 2025

During January’s cold snap, flocks of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) suddenly swarmed backyard bird feeders and everyone wished they would just “Go away!”

As it happens starlings are going away, though maybe not quickly in your backyard.

Despite its success and large numbers, the European Starling is now in steep decline, like so many other species in North America. The current population is half the size it was 50 years ago – down from an estimated 166.2 million breeding birds in 1970 to 85.1 million. The species is also declining in Europe.(*)

— Cornell Chronicle: Starling success traced to rapid adaptation, Feb 2021, emphasis added

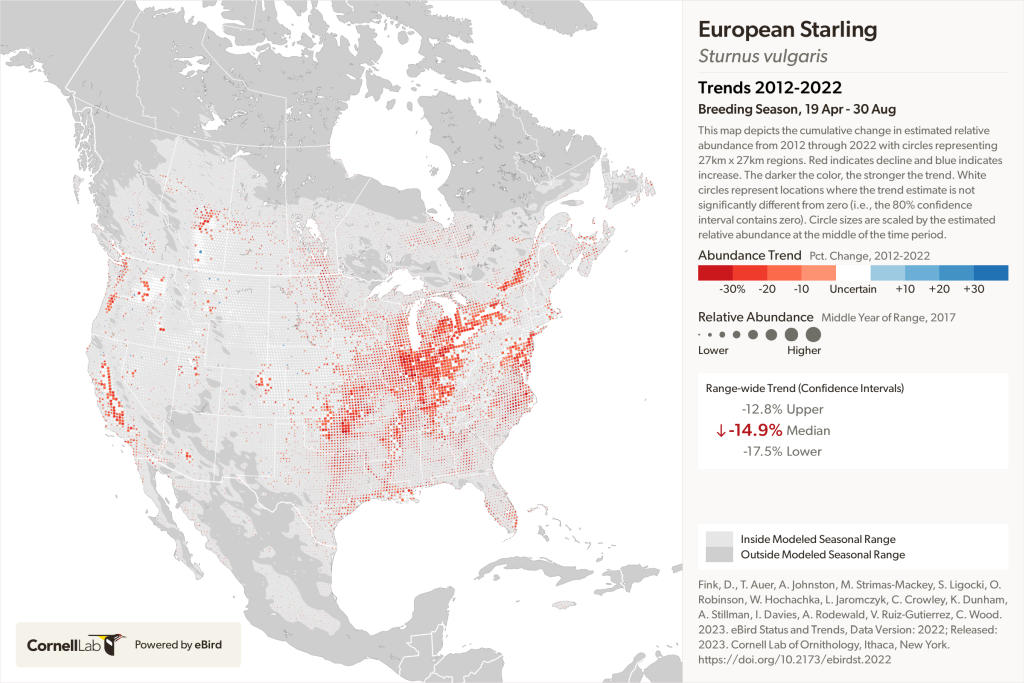

The decline is easy to see in red on eBird’s European starling Trends map, 2012-2022.

In just a decade starlings declined 14.9% in North America, mostly in the Midwest and especially Illinois where they are down 24.5%.

Despite this, many of us worry that starlings are having a negative impact on cavity-nesting native birds — but they are not.

Starlings often take over the nests of native birds, expelling the occupants. With so many starlings around, there is concern about their effect on native bird populations. Nevertheless, a study in 2003 found few actual effects on populations of 27 native species. Only sapsuckers showed declines due to starlings; other species appeared to be holding their own against the invaders.

— All About Birds: European starling account

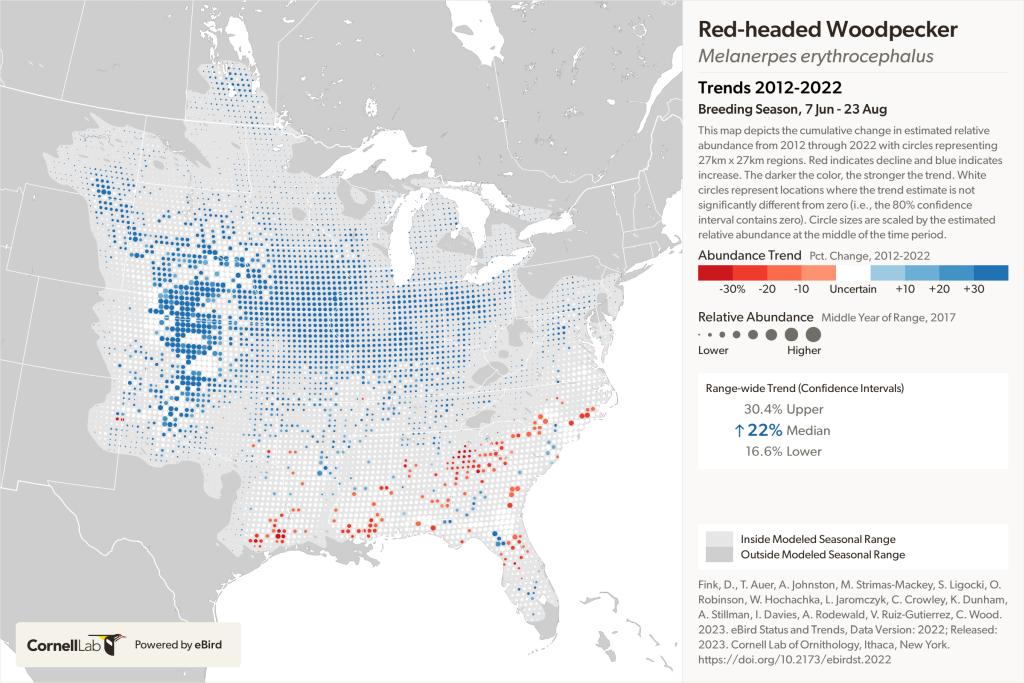

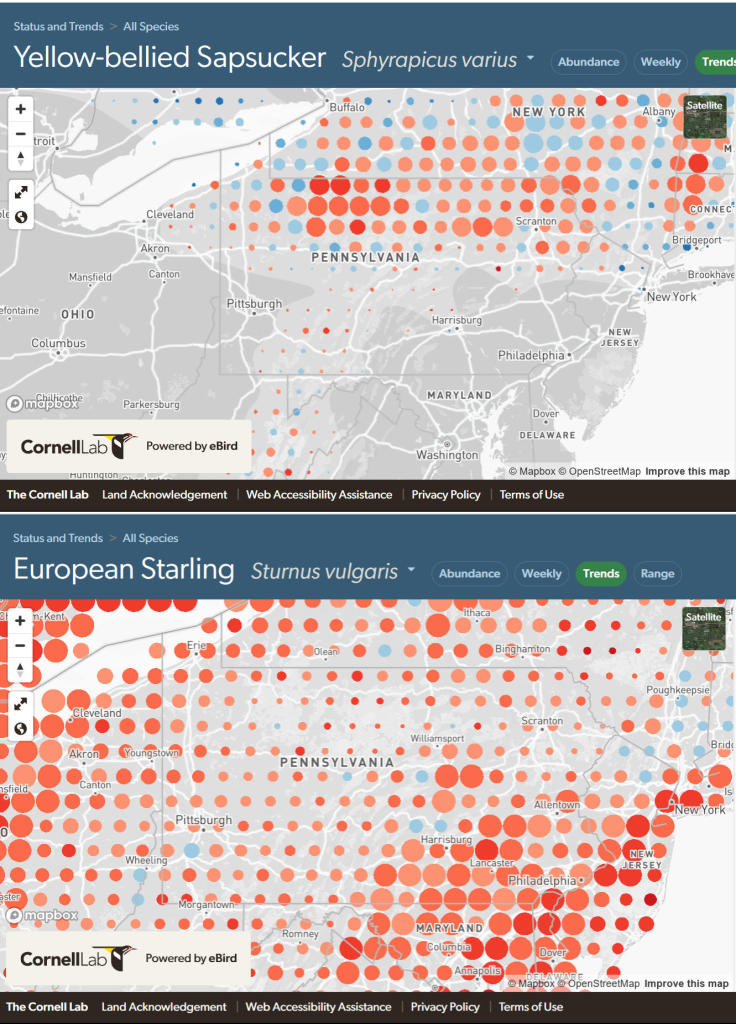

“Only sapsuckers showed declines?” Fortunately this is not quite the case in Pennsylvania. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers have declined in certain regions of PA but in others they have increased. In areas of overlap with starlings, such as the western I-80 corridor, sapsuckers have increased. [I-80 is under the word “Pennsylvania” on the maps below.]

Meanwhile, starlings have declined more than sapsuckers overall and have not appreciably increased in the sapsuckers’ range. Compare the two Trends maps below.

If you don’t like starlings, don’t worry. The problem is taking care of itself.

(*) In the UK the starling population dropped 80% in just 25 years from 1987 to 2012. This is very worrisome because they are a native bird in Europe.