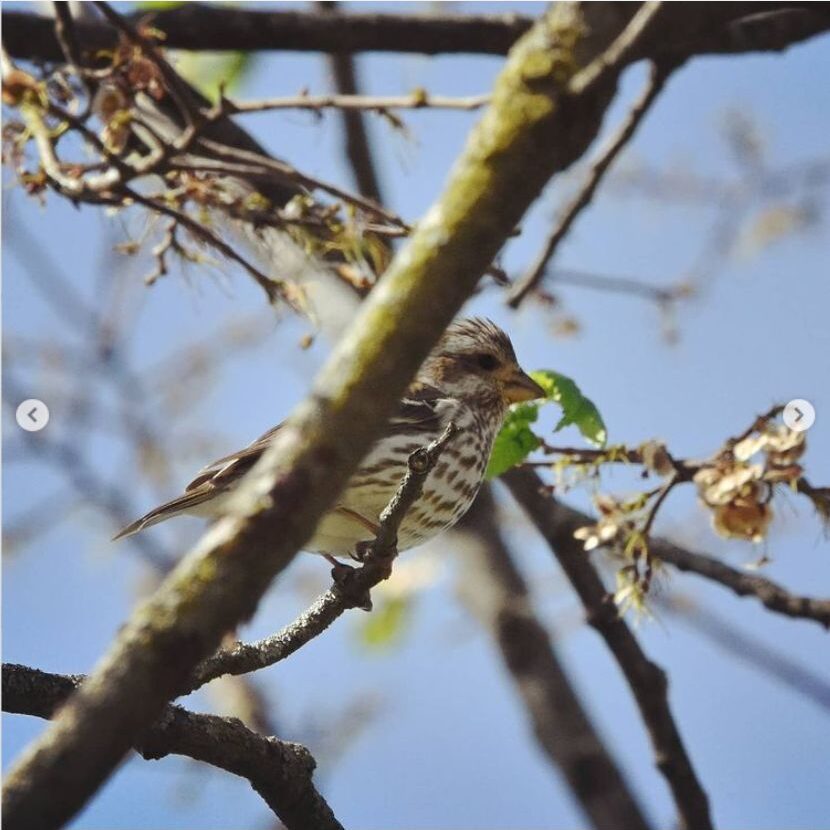

5 May 2021

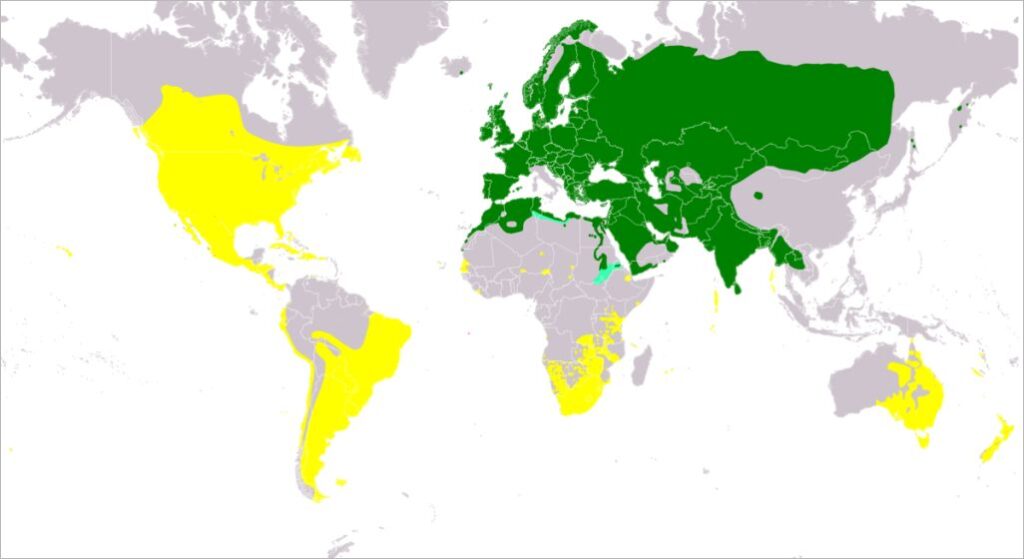

Early May is exciting for Pittsburgh birders as beautiful migratory songbirds arrive in our area. Some come from as far away as South America and are en route to northern Canada. Some stay to nest, others move on. What map are they using? How do they get here?

Much of migration remains a mystery. This list is just a summary of the high points. If you have more to add, please leave a comment!

Basic Onboard Navigation System:

Migratory birds are born with a basic navigation system that improves with experience. First-of-year birds fly south in the fall with these instructions: Fly in [this] direction for [this] long.

Those born with a faulty compass head the wrong way and end up on Rare Bird Alerts.

My Life Bird lark sparrow was found at Seal Harbor, Maine. Though usually a western bird, he flew east instead of south.

Experience:

After a bird has made the trip just once, it remembers the route and retraces it year after year. The lark sparrow in Seal Harbor showed up every September for the typical life span of a lark sparrow. His compass error didn’t hurt him.

Birds can be thrown off course by bad weather but they have additional navigational aids.

“Seeing” Earth’s Magnetic Field:

There’s evidence that birds can “see” Earth’s magnetic field to help them navigate, though we’re not sure how. A 2018 study of European robins and zebra finches reported that a cryptochrome protein in their eyes (Cry4) helps them see the blue light associated with magnetism. Cry4 increases during migration season and ebbs thereafter. Intriguing!

Orienting by polarized light at sunrise and sunset:

Before 2006 scientists knew that birds orient themselves at sunset. Then they learned how.

Researchers from Virginia Tech in Blacksburg and Lund University in Sweden say experiments with savannah sparrows in Alaska show the birds take readings of polarized sunlight at sunrise and sunset and use them to periodically recalibrate their magnetic compasses.

— The Baltimore Sun: Sunlight is key for Bird migration

Navigating by smell:

Birds even use their sense of smell! A study of gray catbirds in 2009 showed that those who’d made the trip before used smell to course-correct.

How do they get here? It’s even more amazing than we thought!

To learn more, click the embedded links above.

(photos by Kuldeep Singh, Suunto, and Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)