Palm warblers (Setophaga palmarum) come in two colors — yellow and brown — and both are seen in Pennsylvania during migration, but we rarely see them together. They follow different paths and have different destinations.

Lauri Shaffer (birdingpPictures.com) found a yellow palm warbler at Montour Preserve in eastern PA in early April, above. Bobby Greene photographed a brown one on migration in Ohio a few years ago, below.

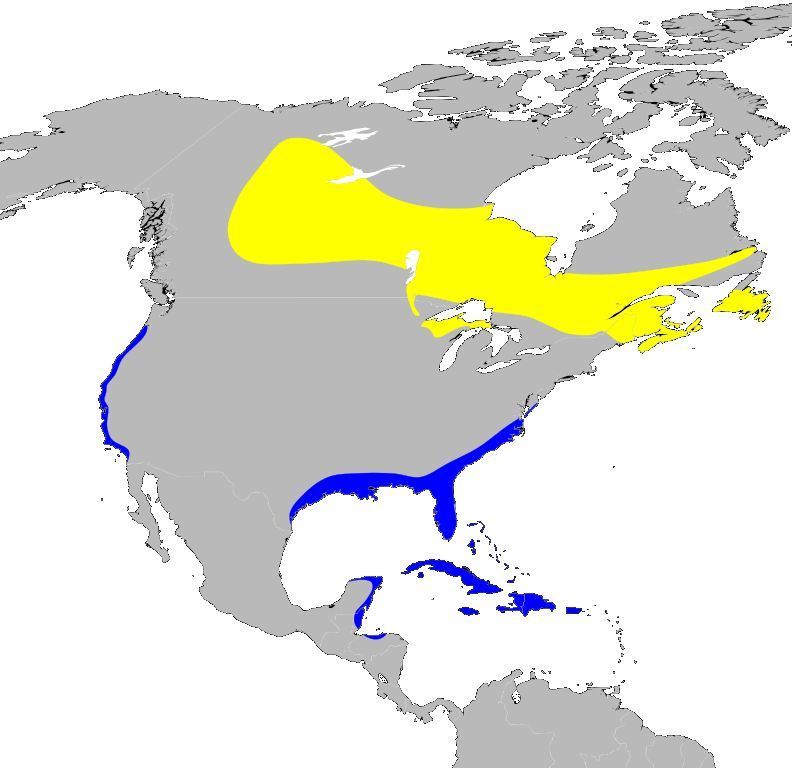

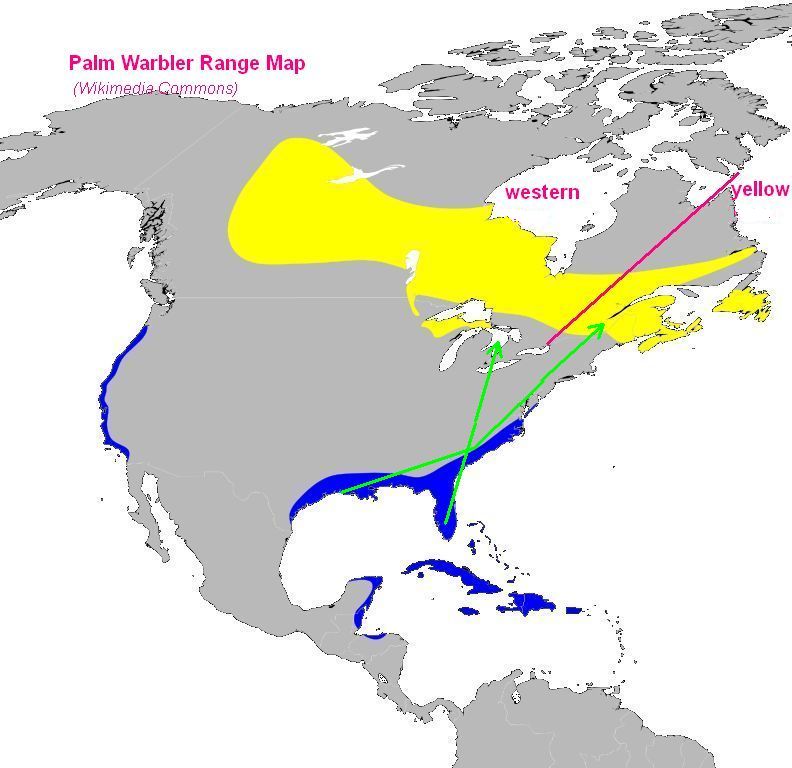

The colors indicate the two subspecies — yellow and western (brown) — that breed in different places, cross over on migration, and overlap their range in winter. The typical range maps don’t tell the story.

Birds of North America Online gives the details, paraphrased below:

Two subspecies of the Palm Warbler exist, easily identified in the field. [They] inhabit separate breeding grounds but overlap on their wintering grounds. The Western Palm Warbler (S. p. palmarum) nests roughly west of Ottawa, Ontario and winters along the southeastern coast of the U.S. and the West Indies. The Yellow Palm Warbler (S. p. hypochrysea) nests east of Ottawa and winters primarily along the Gulf Coast.

paraphrased from Birds of North America Online

For the quickest way to their breeding grounds “yellow” crosses to the Atlantic Flyway in the spring (green arrow going east) while “western” crosses to the Mississippi-Ohio watershed (green arrow going northwest). Their breeding grounds divide at the pink line. On the map it would look like this.

If you’re in the Florida Keys in February you’ll see both of them, as Chuck Tague did when he made this slide.

But don’t expect to see them both in Pittsburgh. Ours are the western palm warbler. It’s a rare day when we find a yellow one.

Read more about palm warbler subspecies in Chuck Tague’s blog: Palm Tree Warblers.

(credits: Yellow palm warbler by Lauri Shaffer, BirdingPictures.com. Brown palm warbler by Robert Greene, Jr. Range maps from Wikimedia Commons, annotated by Kate St. John. Brown and yellow comparison by Chuck Tague)