Believe it or not with practice you can recognize individual song sparrows by voice.

I learned this when I read about the pioneering work of Margaret Morse Nice in Columbus, Ohio. In 1928 she began an eight year study of song sparrows at her home along the Olentangy River. Her Studies in the life history of the Song Sparrow changed the course of American ornithology.

Margaret Morse Nice banded the song sparrows and made meticulous observations of their behavior. She listened carefully to their songs and wrote down the variations including the phrases they borrowed from neighbors.

Her research spawned many studies of song development. We now know that: Songbirds learn their songs by listening when they are adolescents, practicing phrases, and eventually mastering their species song. Each bird then improvises to make the song his own. The males work hard to be skilled and unique singers because the females are attracted by the best courtship songs.

I wondered if I could recognize an individual’s song so I started at home.

My backyard is the territory of a male song sparrow whose tune I hear every morning. Eventually I learned his morning song(*). If I could write musical notation I’d put it here.

From my front porch I can hear “my” song sparrow and my neighbor’s front yard sparrow counter-singing to maintain their territories. I know those two don’t sound the same.

I can’t identify more than one tune yet but I can recognize “my” song sparrow in the morning now.

Try it and see.

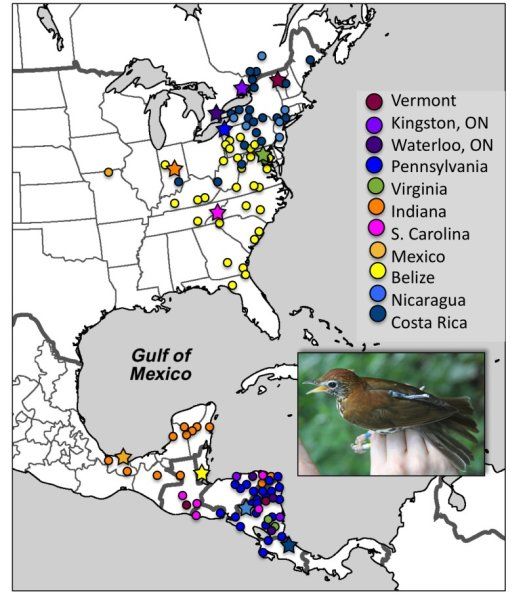

(photo by Peter Bell)

(*) Dr. Tony Bledsoe says that each song sparrow may have up to five distinct songs. So though I’ve learned the “Good morning” tune I’ve got a lot more learning to do!