In the middle of May, Schenley Park’s bird population bursts at the seams as migrants stopover on their way to Canada. Early this week one of the most numerous visitors was the Swainson’s thrush.

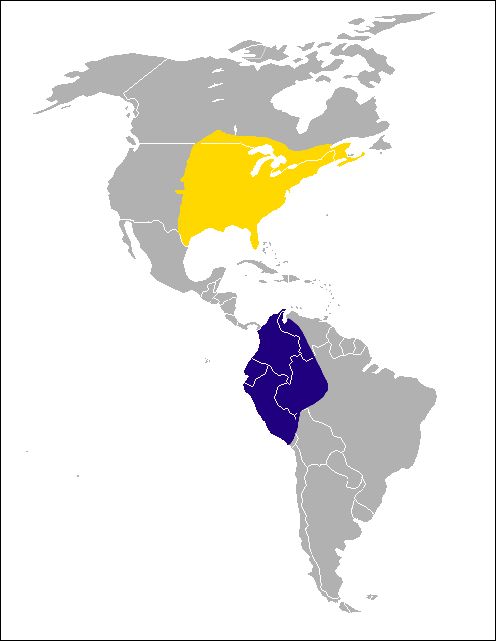

We tend to take their migration for granted, knowing the birds make long journeys from South to North America, but we’re unable to visualize it. How far do they go? How long do they live?

Last December in the Columbian highlands a bird banding station captured a previously banded Swainson’s thrush. Its bands revealed the bird was captured more than five years earlier while on its journey north.

The thrush was banded near Unadilla, Nebraska in May 2008, heading home to breed in central Canada. At that time it was at least one year old. In December 2013 it was recaptured near Las Margaritas, Columbia 2,700 miles away, probably at its winter home. It was more than six years old and had made the journey at least 13 times.

From Canada to Columbia, read about this bird’s journey and see the map at Klamath Call Note.

(photo of a Swainson’s thrush on migration in Pennsylvania by Steve Gosser)