19 September 2023

Right now warbler migration is at its autumn peak in southwestern Pennsylvania but, as usual, the birds are hard to identify. Their fall plumage is dull and confusing, they move fast so we never get a good look at them, and we don’t get much practice because many of them are here only in September. And then they’re gone.

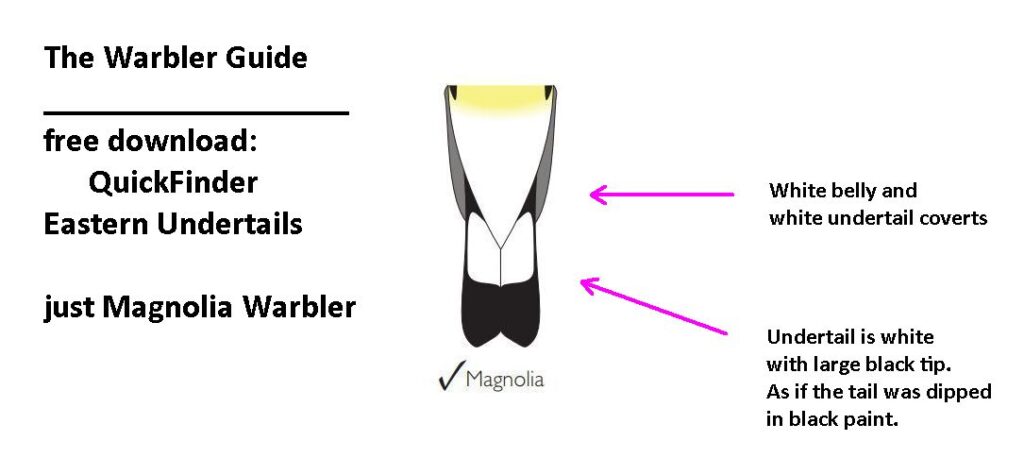

This year it dawned on me that the magnolia warbler (Setophaga magnolia) is super-easy to identify if all you see is its butt, as shown at top and below.

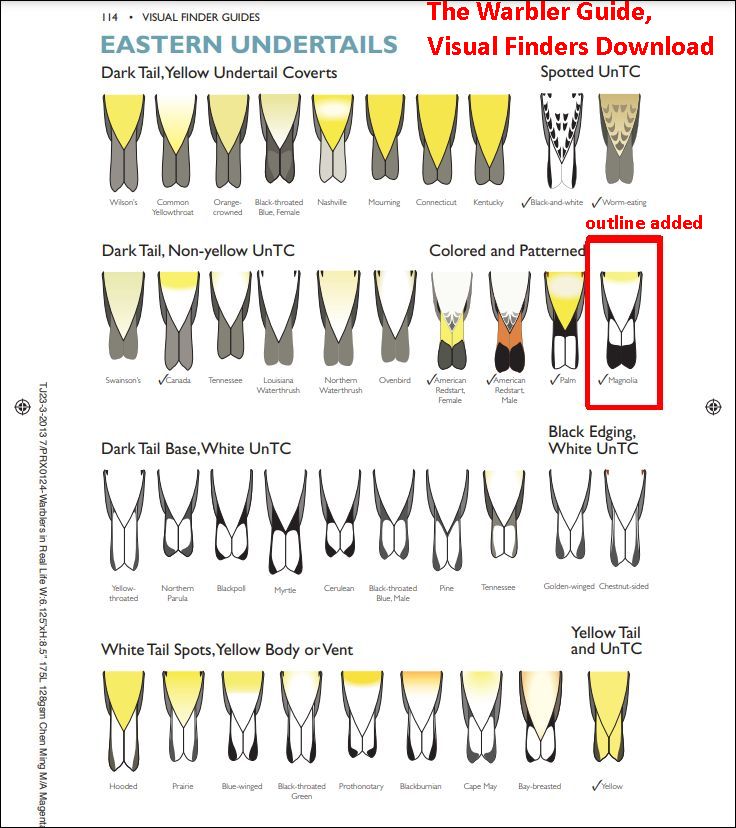

The “maggie” has a unique pattern on its undertail, easy to see on the free Visual Finders PDF, downloaded from The Warbler Guide. I’ve highlighted the magnolia warbler on this screenshot of Page 15.

Note that the magnolia warbler is the only warbler with a white belly, white undertail coverts, white undertail and a large black straight-edged tip on the tail. It looks as if this warbler was dipped tail first in black paint.

On some juveniles the tip is dark gray but the pattern is the same.

So this view is the best way to identify a magnolia warbler.

The undertail tells the tale!

Download Stephenson & Whittle’s free Visual Finders PDF at The Warbler Guide.

(photos by Dave Brooke, diagrams from The Warbler Guide free download)

I highly recommend the 560-page The Warbler Guide by Tom Stephenson and Scott Whittle which I use at home after noting the warbler’s key features in the field. In my opinion the book is indispensable if you take photographs.