12 June 2023

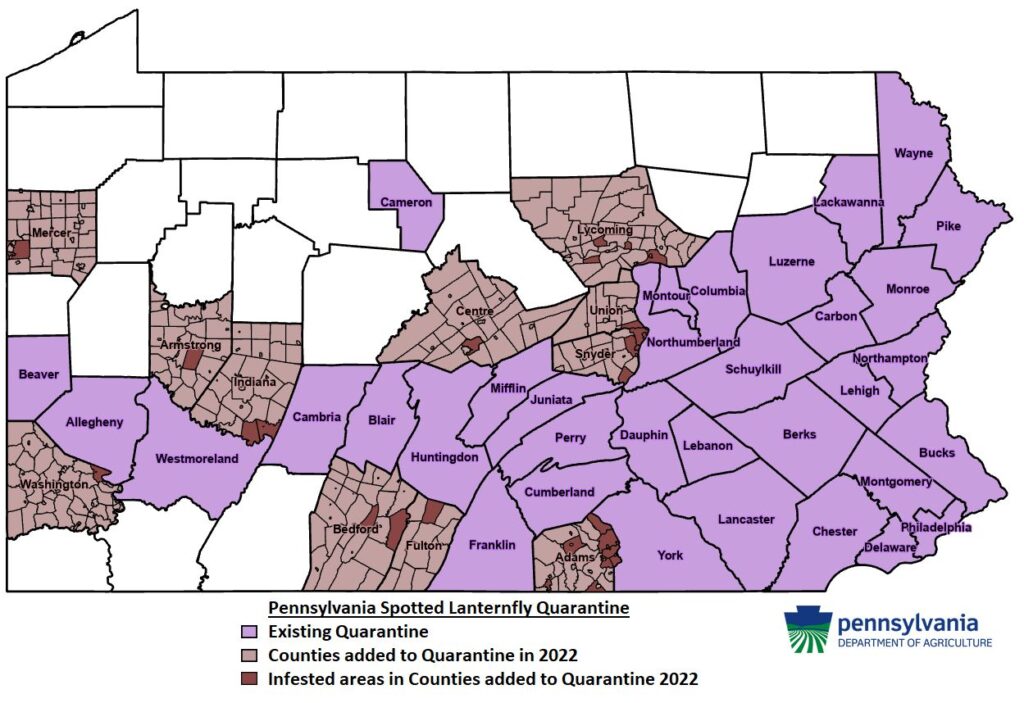

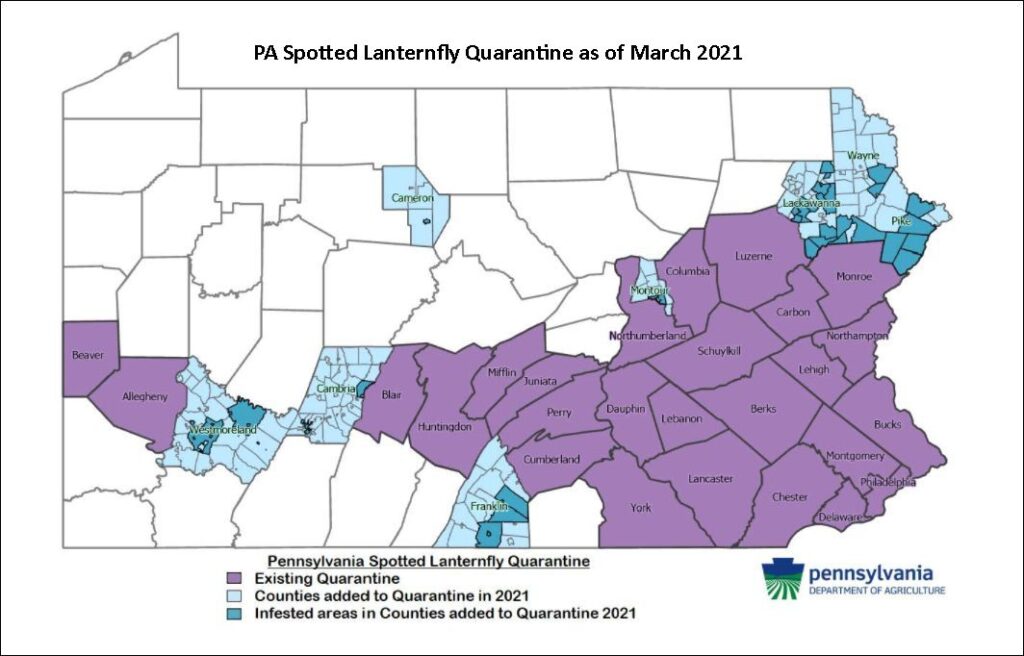

They’re here, they’re creepy and they’re not going away any time soon. Spotted lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) have made it to Pittsburgh and are following the typical trajectory of invasive insect pests: Barely noticeable (2018) to Overwhelming (2022, 2023+) to Hard to Find (declines in about 3 years: 2025).

The most important thing to remember is this from Penn State Extension: Avoid overreacting to the situation and teach others not to overreact. Insecticides won’t eradicate the pests but will kill the good bugs, bees and butterflies. Instead, let’s outsmart spotted lanternflies.

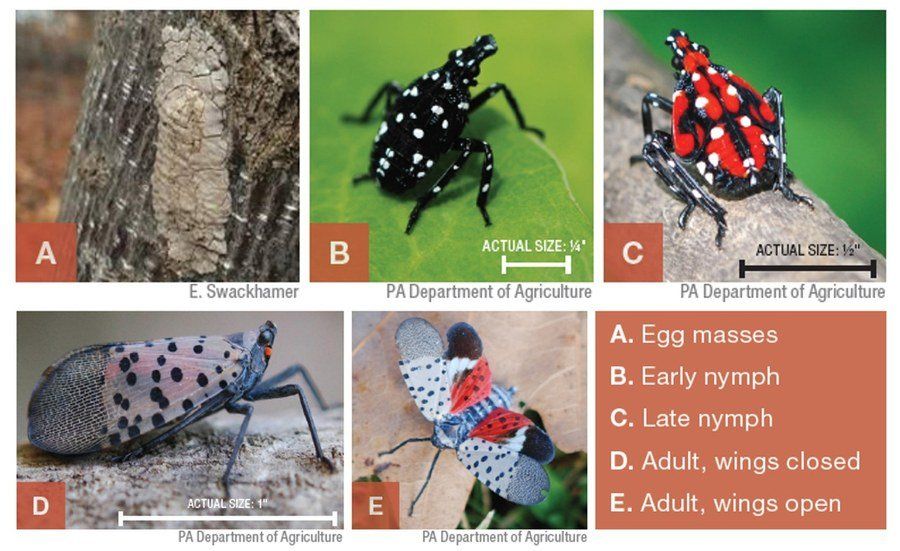

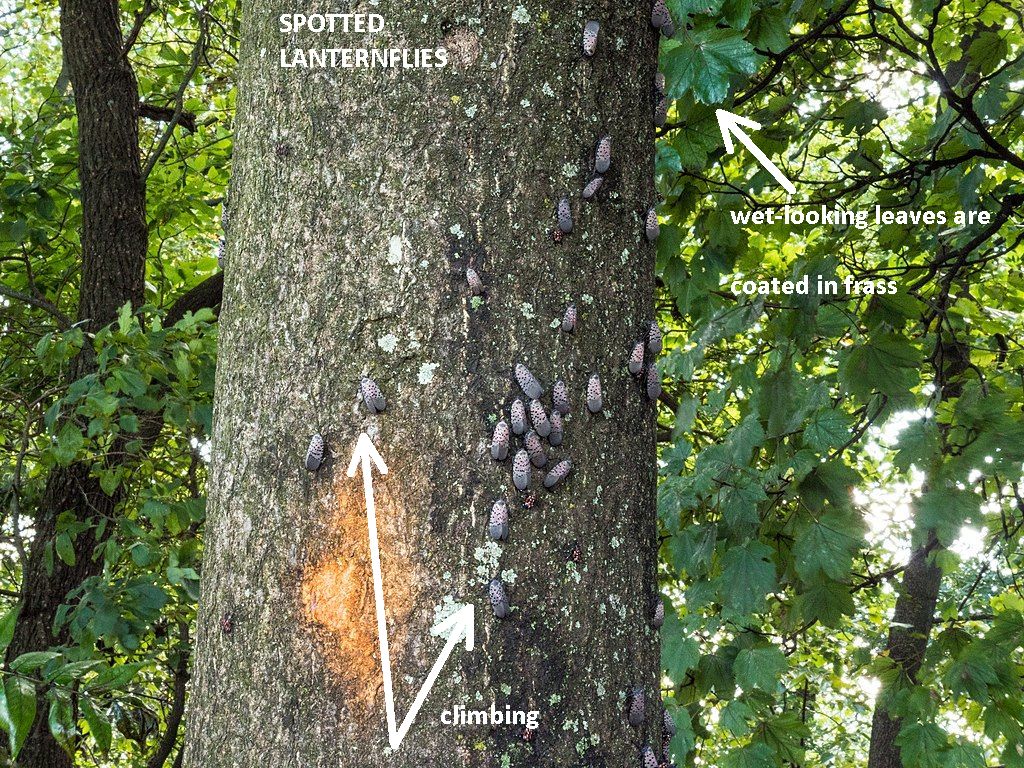

First, know the enemy and its weakness: Spotted lanternflies can only crawl up, they can’t reverse!

Second, learn how to manage them. This month Penn State Extension educator Sandy Feather is presenting practical in-person advice on how residents can contribute to combating the problem. I’m late to let you know about these two remaining classes:

- June 12 — 6-8 p.m. at Frick Environmental Center, Point Breeze [tonight!]

- June 14 — 2:30-5:30 p.m. at Pittsburgh Botanic Garden, North Fayette

You can also learn online from Penn State Extension’s Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide.

Third, protect a favorite tree using this circle trap (video below). You can make your own circle trap or buy one here. Do not use sticky tape as it traps and kills birds (trying to eat the bugs) and beneficial insects.

Fourth, be brave. Yesterday Claire Staples outsmarted hundreds of spotted lanternfly nymphs by smashing them with her bare hands! Here are her photos and a quote from her email. (How many nymphs can you see in the right hand photo?)

I killed over 200 in a 10 foot section along the power lines through Swisshelm Park slag heap. It was the only place where we found them but it was amazing to see the density. It was really easy to get them and my granddaughter watched and only a few escaped. I would take the small branch with the bugs in the palm of my hand and place the other palm on [top of] it and start rolling my hands together. I was amazed that my hands appeared clean and there was no odor. I did wash my hands later but I was surprised that there was no residue.

— email from Claire Staples, 11 June 2023

That’s braver than I would have been!

Meanwhile, the lanternfly population will eventually decline on its own. Here’s what happened in Berks County, PA where spotted lanternflies were first discovered:

- 2014: Barely noticeable. Spotted lanternfly first discovered in U.S.in Berks.

- 2018, 2019: Overwhelming. Everywhere! Some commercial grapevines killed.

- 2021: Hard to find. Everyone says, “Where have all the spotted lanternflies gone?“

(photos from Wikimedia Commons and Claire Staples; video embedded from Penn State Extension)