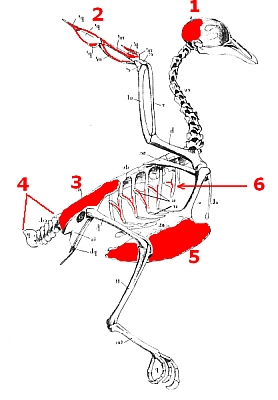

Birds molt at least once a year to replace worn out feathers. This process permits them to wear different plumages.

Some birds, like the American robin, look the same before and after. Others radically change their appearance by replacing their fancy breeding feathers with plainer plumes. Male scarlet tanagers are an extreme example: They’re red while breeding and green while not.

Molt and plumage terminology was standardized in 1959 by Humphrey and Parkes who divided plumage names into three main types. (*)

- Juvenile plumage is worn by young fledged birds.

- Basic plumage is what birds acquire during their annual post-breeding molt. We often call this “non-breeding” or “winter” plumage but these terms are inaccurate. Adult robins are always in basic plumage even when they’re breeding, and “winter” describes the weather North America is experiencing while the bird is away. To South American birders, a green scarlet tanager is in summer plumage.

- Alternate plumage is optional. Some birds don’t undergo a second molt but those who do put on their finest feathers in time for the breeding season. This is often called breeding plumage.

In some species it takes several years for the young to mature so they progress through as many plumage cycles as it takes to become adults. Young ring-billed gulls go through three cycles: Basic 1, Alternate 1, Basic 2, Alternate 2, Basic 3, Alternate 3. Gulls are complicated.

American avocets aren’t quite so complex. They molt their wing feathers once a year but change out their head and neck feathers twice a year from basic plumage (white) to alternate plumage (ochre) for the breeding season.

The avocets above are lined up in perfect sequence during their post-breeding molt in August. The bird standing on the left is closest to basic plumage, the bird on the right is closest to alternate plumage, and the bird in the middle is halfway between.

Below, another flock has the lead bird closest to alternate plumage and the trailing bird closest to basic.

Look closely at each bird and you can see that the wings of the 1st, 3rd and 4th birds have ragged trailing edges because they’re molting their wing feathers. The 2nd and last birds have perfect wings, so my guess is that they’re juveniles. Juveniles don’t molt their fresh new wing feathers until they’re a year old.

When avocets have completed their molt into basic plumage their heads and necks are gray-white like this bird photographed in September.

Experts in molt and plumage can probably tell the age of these birds by their appearance.

Not I. Aging shorebirds by plumage is my final frontier.

(Inspiration for this Tenth Page is from page 110 of Ornithology by Frank B. Gill.

All photos by Bobby Greene)

(*) If you’re a plumage expert, please feel free to correct me. I’m still learning!

P.S. TO PEREGRINE FANS: Molting is a wonderful thing. Last May the male peregrine at Pitt, E2, chased off an intruder but not before this opponent damaged one of his primary feathers. This gave him a “hole” in his wing. Over the summer he completed his annual pre-basic molt and grew all new feathers. Now his wings are perfect. No gap.