24 October 2021

Is there a safe way to watch this volcano?

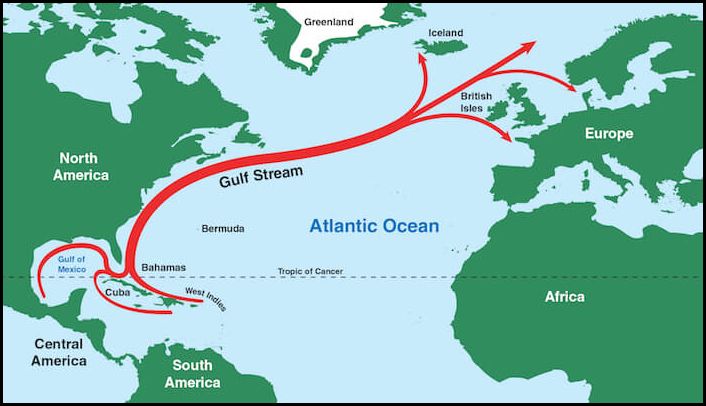

After eight days of earthquakes in mid-September the Cumbre Vieja volcano on La Palma (Canary Islands) began erupting on 19 September 2021. At first people watched nearby but the eruption intensified. Lava started flowing to the Atlantic Ocean.

By the end of September the lava flow was building a delta, as seen by satellites.

On 17 October 2021 Reuters reported the volcano is showing no signs of subsiding anytime soon.

Streams of lava have laid waste to more than 742 hectares (1,833 acres) of land and destroyed almost 2,000 buildings on La Palma since the volcano started erupting on Sept. 19.

About 7,000 people have been evacuated from their homes on the island, which has about 83,000 inhabitants and forms part of the Canary Islands archipelago off northwestern Africa.

All of the 38 flights which were scheduled to arrive or take off from La Palma airport on Sunday [17 Oct] were cancelled because of ash from the volcano.

— Reuters: No end in sight to volcanic eruption on Spain’s La Palma, 17 Oct 2021

The Reuters video at this link shows how the eruption has affected the islands. Click here for an aerial flyover of the lava flow. It is sobering.

By now the eruption is far too dangerous to watch in the vicinity but we can view it Live on YouTube at: Live La Palma volcano eruption.

For best viewing watch the volcano after dark. Since the Canary Islands are off the coast of Africa, they are 5 hours ahead of Eastern Daylight Time. In the eastern U.S. begin watching in late afternoon to see lava flowing at night.

p.s. The Cumbre Vieja (Old Summit) volcano is located on La Palma, the upper left island below.

(photos and map from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)