The akiapola’au (Hemignathus wilsoni), or aki’, is a Hawaiian honeycreeper with such a small population and such a restricted range that he may well go extinct in this century. He’s hard to find, of course, but he’s well worth the effort.

The aki’s beak is most unusual but it’s perfect for gathering what he eats. He probes for spiders, beetles and caterpillars and, like a sapsucker, he drills rows of holes in an “aki’ tree” and returns when the sap wells up.

Despite his similar food requirements the aki’ doesn’t have a woodpecker beak. Instead his lower mandible is short and straight with a chisel tip while his upper mandible is long and thin, curved down, and flexible.

Each half of his beak has a different purpose. He chisels and pecks with the lower mandible or props it in place while he probes and scrapes with his upper mandible. As you can see in the top photo, there’s even a small gap between the two mandibles. How strange!

The males and females forage in different micro habitats. The females look similar, though paler.

The aki’ is listed as Endangered for good reason. His population is small and declining. As of 1995 there were only 800 individuals left on Earth, scattered in severely fragmented areas in the mountains above 5,000 feet.

Many things contribute to the aki’s decline including habitat loss from logging and farming and predation by introduced species, especially rats, cats and dogs. The aki’ is also threatened by avian diseases carried by mosquitoes; Hawaiian birds have no immunity to them. The mosquitoes, accidentally introduced to Hawaii beginning in 1826, cannot live in the cold climate above 5,000 feet. That’s why Hawaiian honeycreepers like the aki’ still survive there.

Unfortunately climate change is warming the Hawaiian mountains and the mosquitoes are moving up. How long will we still be able to find this beautiful bird with such an unusual beak?

(photos on by Aaron Budgor, Bettina Arrigoni and Eric Gropp via Flickr Creative Commons license. click on the captions to see the originals)

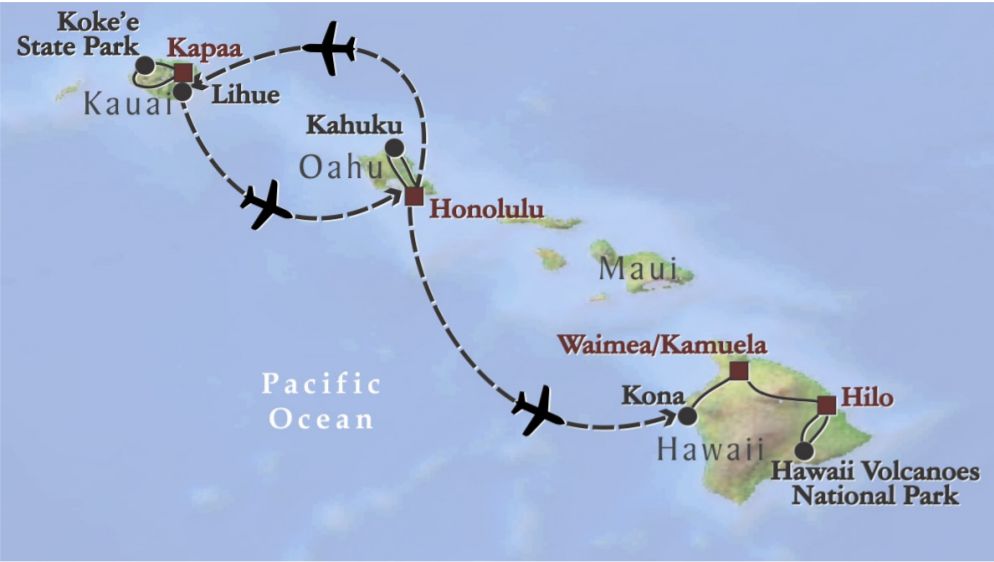

Tour Day 7: Mauna Kea, Saddle Road, the Big Island, Hawaii

p.s. I saw an aki’ yesterday. Yay!