When I saw forty sandhill cranes near Volant, Pennsylvania on Monday, I thought of the time I saw 500,000 in Nebraska in March 2004. Half a million sandhill cranes are a breathtaking, exhilarating, stupendous experience! It has to be seen in person. Here’s what it’s like.

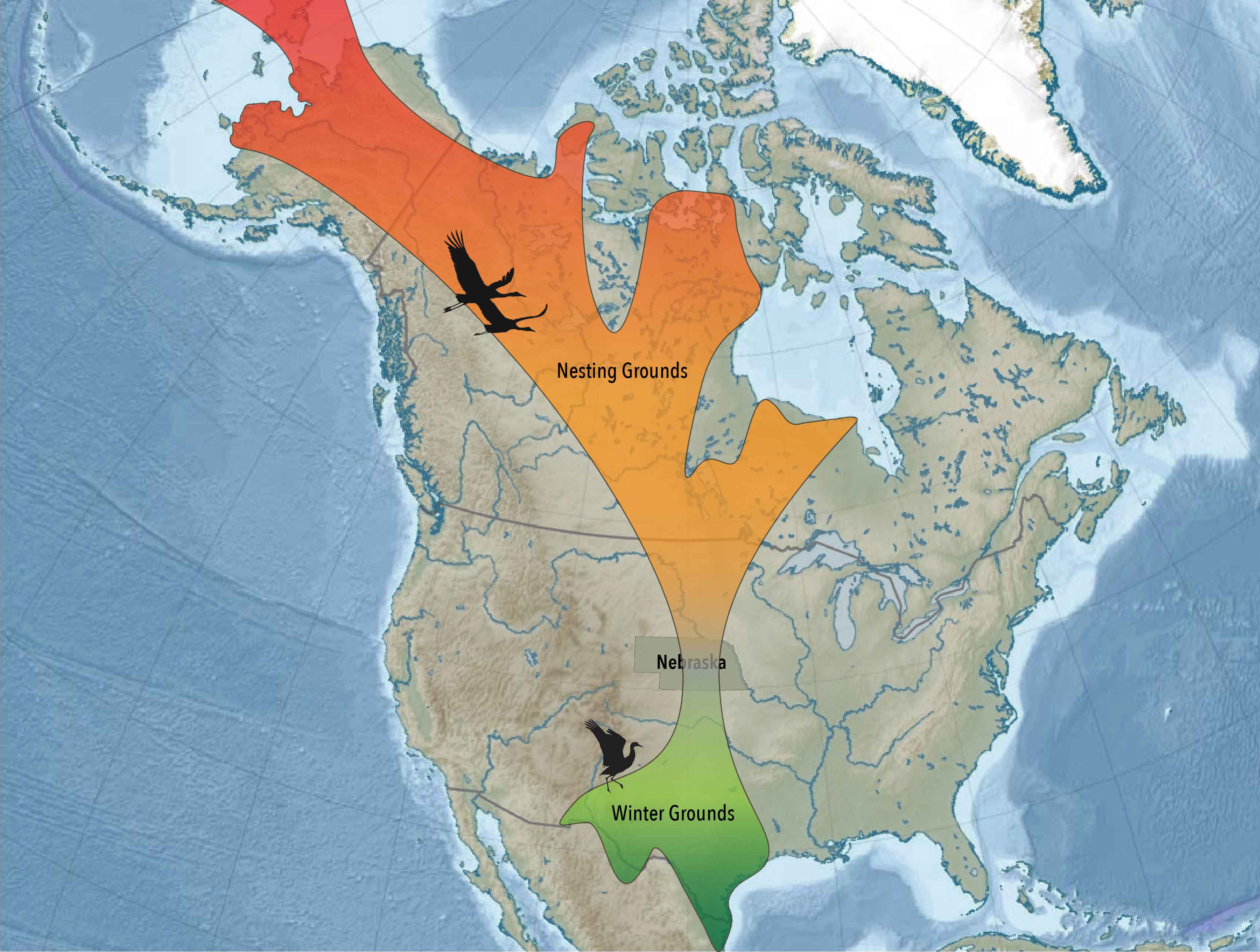

Every spring the cranes leave their wintering grounds in Mexico and Texas to converge on an 80-mile stretch of the Platte River in Nebraska. Their numbers peak in March when 80% of all the sandhill cranes on Earth are there.

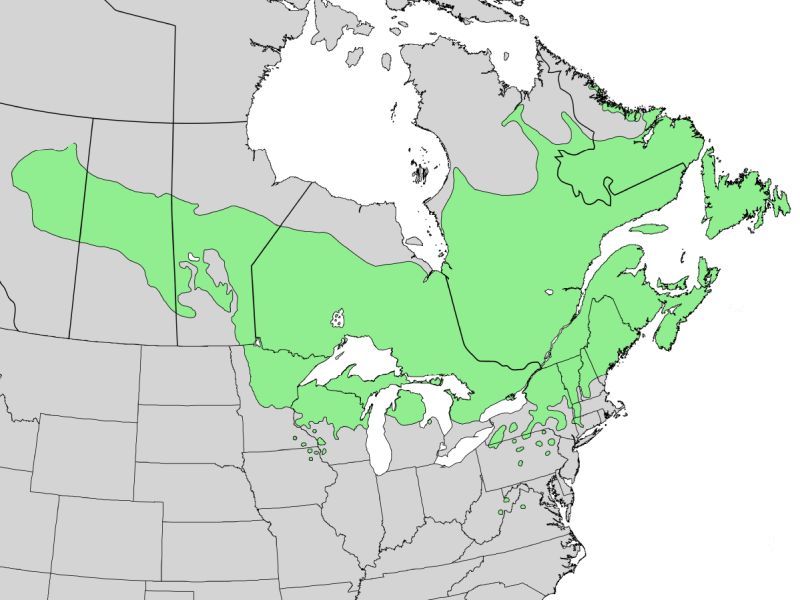

Cranes are drawn to this location because the Platte is still “a mile wide and an inch deep” between Lexington and Grand Island. The water is shallow enough to roost in overnight and there’s abundant plant food in local wetlands and waste corn in the cattle fields(*). The cranes spend three to four weeks fattening up for their 3,000 mile journey to their breeding grounds in Canada, Alaska and Siberia.

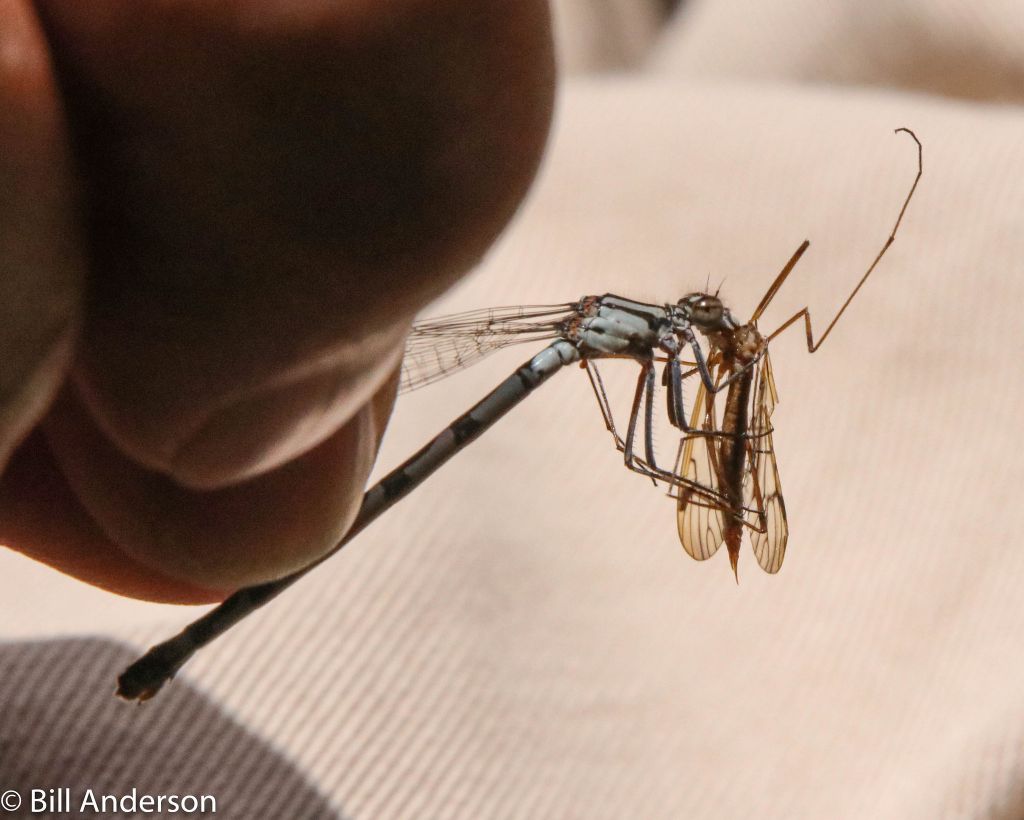

At dusk and dawn they move to and from the Platte River in spectacular numbers. Their sight and sound is amazing, especially when you’re in a bird blind near the action. They dance with their mates and jump for joy.

I saw their great migration in late March 2004. Before my trip I booked dusk and dawn visits to the bird blinds at the Platte, then I flew to Omaha and drove west to Grand Island and Kearny (pronounced Karney). I didn’t mind the 2.5 hour drive because I wanted to see a piece of the Great Plains and experience this: For over 100 miles there are no cranes at all then suddenly, just as I-80 approaches the Platte River, the sky is filled with them. I’d arrived!

I saw hundreds of thousands of sandhill cranes at dusk and dawn and spent my days at local birding hotspots where my highlights were white pelicans, burrowing owls, lapland longspurs, and a Harris’ sparrow. I had hoped to see a whooping crane but I was too early that year. (Whoopers leave Texas later than the sandhills.)

This 8-minute video from The Crane Trust gives you another view of the spectacle.

Nothing can beat the sandhill cranes’ migration in Nebraska in March! Don’t miss it!

For information on seeing the cranes’ migration visit Nebraska Flyway‘s website with links to Sandhill Viewing, lodging and food, brochures and maps.

(photo credits: cranes at the Platte from Wikimedia Commons, map of crane migration linked from Visit Grand Island, click on the captions to see the originals. YouTube video by The Chicago Tribune)

(*) There’s a connection between beef and cranes: Half a million sandhill cranes get enough to eat in Nebraska because there’s leftover corn in the cattle fields. There are more cattle than humans in Nebraska.