A week ago I was at the 19th annual Snow Goose Festival in Chico, California. Located in the north Central Valley, it’s a great place to see birds in January. 44% of the waterfowl in the Pacific Flyway spend the winter there! Here are some impressions from my trip. (Note: bird photos are from Wikimedia Commons.)

What attracts so many ducks and geese to the Central Valley? It’s obvious from the air. The land is flooded with shallow ponds (rice fields) and wetlands.

In winter a million geese come to stay: greater white-fronted geese, snow geese, and some Ross’s geese. Ross’s geese look the same as snow geese but they’re smaller and hard to pick out. At the Festival I learned an easy way to identify a Ross’s goose in flight: Look for an obviously small goose in a V of snow geese. Ta dah!

The most plentiful duck in winter is the northern pintail, far outnumbering all other species. Scanning the thousands of ducks at Llano Seco, the majority were pintails with American wigeons and northern shovelers mixed in. Mallards were rare.

In January the flowers bloom because it’s the rainy season. These pipevine flowers were in Upper Bidwell Park.

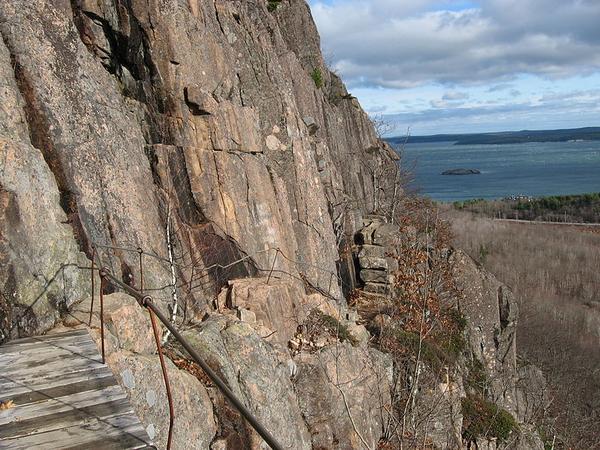

At Lime Saddle we saw the upper reaches of the Feather River, now a tributary inside Lake Oroville reservoir. When the reservoir is full, the water reaches the tree line. It’s low now; perhaps they’re being cautious. Last year the spillways broke and forced the evacuation of 188,000 people.

At Lime Saddle we hiked near the flume, a man-made canal that bypasses Lake Oroville reservoir. Because I’m from the East, California water rights are strange to me. Just as in the early days of cell networks when each carrier erected its own tower, water-owners in California build their own watercourses to separate their water from other uses.

Just before sunset white-faced ibises fly in to Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge to roost.

And after sunset the ducks and geese leave the refuge to go feed in the rice fields at night, thus avoiding the hunters.

A beautiful end to my trip in California’s Central Valley.

(bird photos from Wikimedia Commons; click on the images to see the originals. All other photos by Kate St. John)