27 January 2017

This morning I’m on my way to a 10-day Road Scholar birding trip in Costa Rica. I’m sure to see many Life Birds as well as the National Bird, the clay-colored thrush.

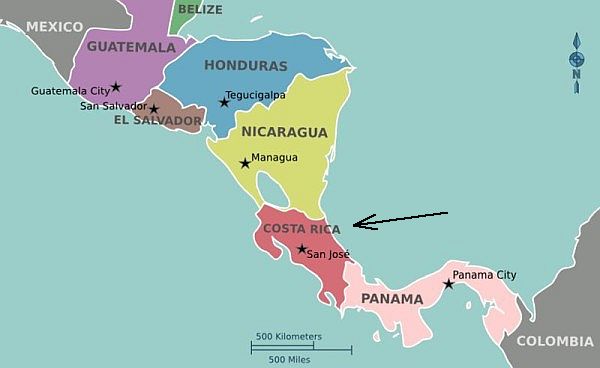

I’ve never been to Costa Rica but I’ve heard great things about it. Located in Central America directly south of Ohio, Costa Rica is about the size of West Virginia with a population of 4.8 million people. It’s an eco-tourism destination famous for friendly people, good food, and its many national parks and nature preserves.

Costa Rica has a lot of birds! My Costa Rican field guide lists 903 species including 54 hummingbirds and 79 flycatchers. Some are endemic to the tropics while others, like the ruby-throated hummingbird, only spend the winter there.

The large number of birds is directly related to the country’s diverse habitats. From the mountains to the sea, an elevation change of over 12,000 feet provides a wide range of climate zones. There are temperate dry uplands and tropical rainforests where the national flower, the Guaria Morada orchid (Guarianthe skinneri), grows.

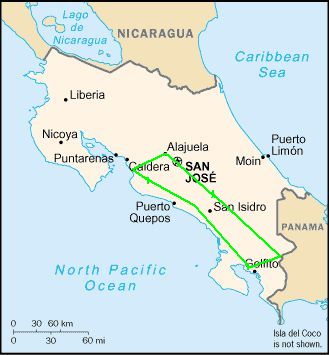

If you’ve been to Costa Rica you’ll be curious about my route so I’ve drawn it in green on the map below. We’ll be traveling counterclockwise from San Jose to sea level at the Pacific, then over the mountains to the 7,000-ft home of the quetzal.

I know that Internet access will be unpredictable so I’ve written all 10 days of blog posts in advance. My husband Rick (who’s too near-sighted to go birding) is holding down the fort at home while my friend Donna Memon posts the blogs to Facebook and Twitter, moderates your comments, and responds to questions.

For now, I’m (mostly) off the grid. I’ll “see” you when I return to my computer on Tuesday morning, February 7.

(photo and maps from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the images to see the originals.)

Day 1: Fly to San José, transfer to Alajuela