6 September 2024: Day 0, Arrive in Seville, Spain WINGS Spain in Autumn

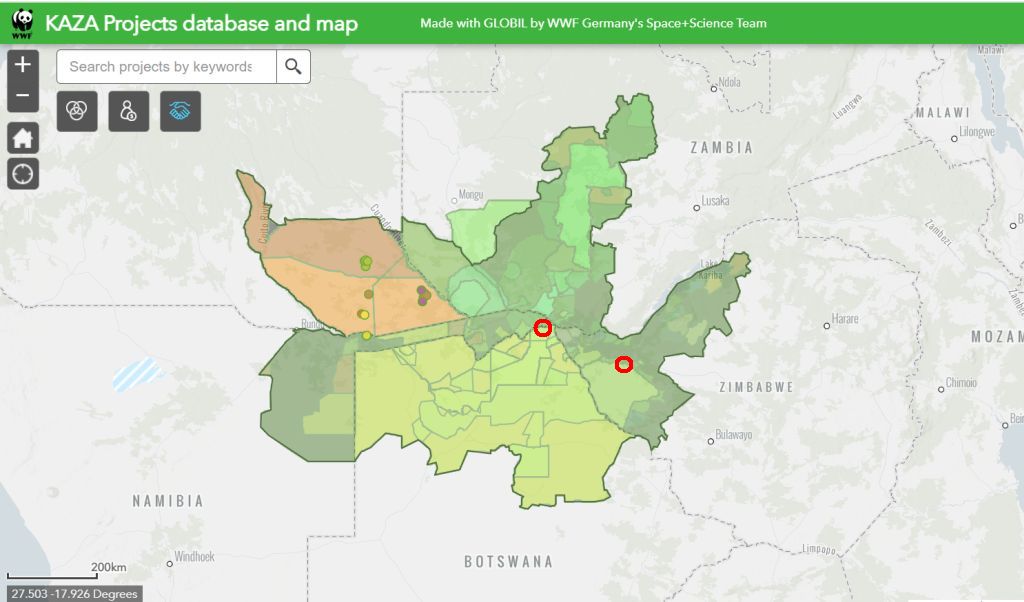

Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

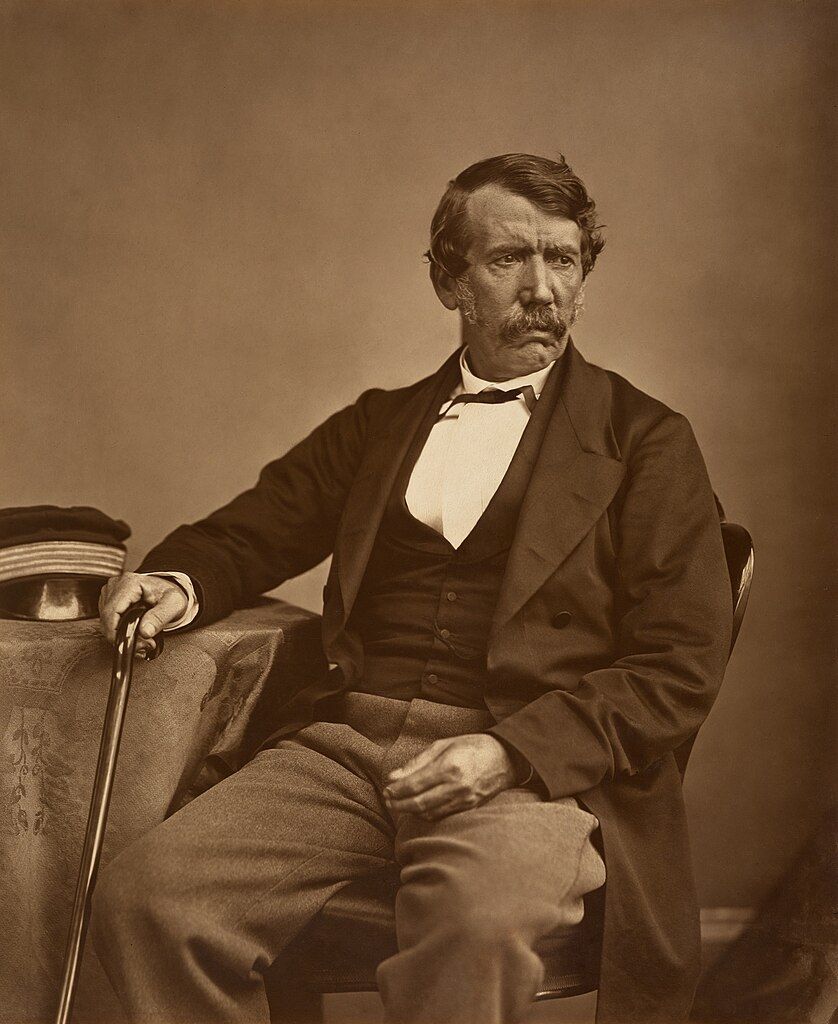

Today I will land twice on the Iberian peninsula, at Lisbon, Portugal and Seville, Spain. It is the only home of the Spanish eagle* (Aquila adalberti), pictured above.

If all goes as planned I will land in Seville at 3:40pm Central European Summer Time (9:40am in Pittsburgh). Tonight our group will spend a night near the airport, then set out early tomorrow for our birding adventure. Since we won’t have time to study Spain’s culture and history, I’ll use this opportunity to describe the towns where we’ll be staying, marked on the WINGS map below.

embedded Google map from WINGS Birding Tours

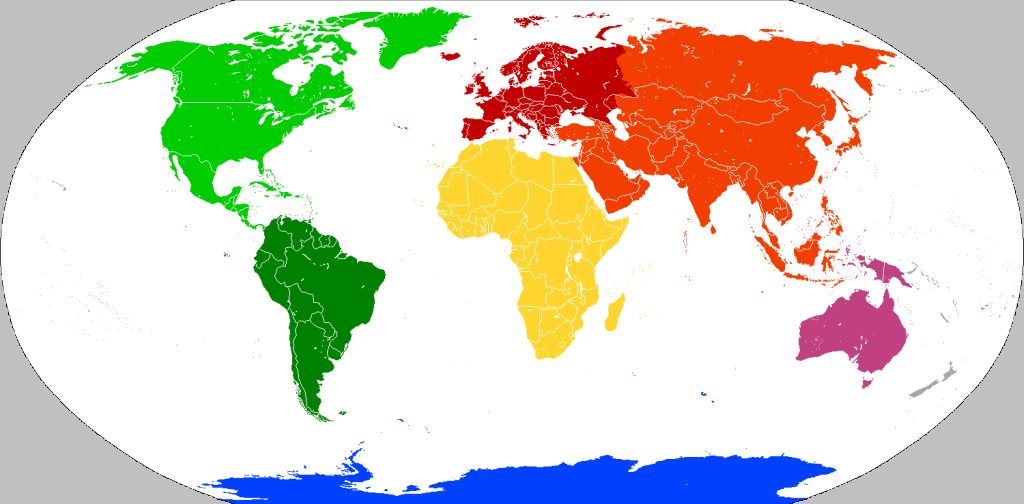

Our trip is entirely within Andalusia, the autonomous community that covers southern Spain. Located between Europe, Africa, the Atlantic Ocean, and the Mediterranean Sea, Andalusia has attracted immigrants, traders and conquerors throughout its history including ancient Iberians, Celts, Phoenicians, Romans, Visigoths and Arabs. We will see their influences in the towns we visit.

Seville

Points A, B & G on the map, our tour will spend one night near the airport at the start of the trip. At the end I will stay one night at the same hotel before my 6:30am flight home the next day. We will not see much of Seville.

Seville is the fourth largest city in Spain and its only inland port. Founded in the 8th century BC in the Guadalquivir River Valley (the “frying pan of Spain”) summers are long, hot and dry (average 97°F in July, 88°F in September). Seville’s history is evident in its famous buildings, two of which are pictured here — one Catholic, one Muslim.

Chipiona

Point C on the map: 2 nights.

Chipiona is on the Atlantic coast near the mouth of the Guadalquivir River where the Salmedina Rocks are a hazard to navigation. The Romans built a lighthouse there and named the town for the Roman Consul who commissioned it. The present lighthouse, built in 1867, is the tallest in Spain and 5th tallest in the world.

Chipiona’s riverfront is packed with ancient buildings including Chipiona Castle, built in the 13th century.

The town has a popular beach on its Atlantic waterfront where highs in July are 84°F, in September 81°F. Needless to say, the birds are on the river side.

Tarifa

Point D on the map: 5 nights.

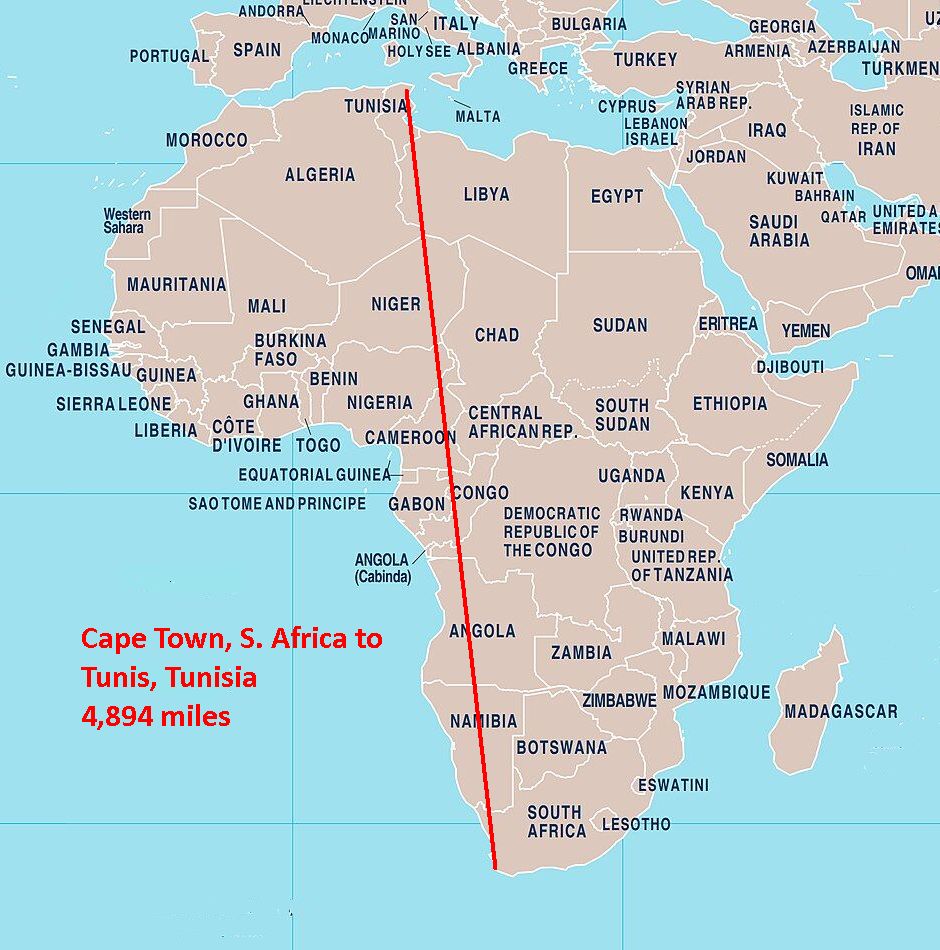

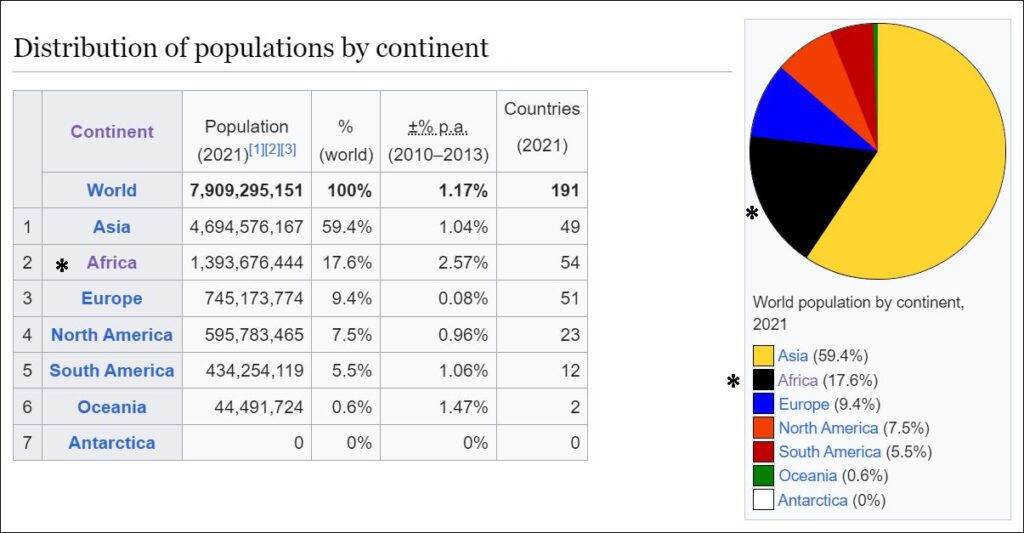

The southernmost point in Europe and gateway to Africa, Tarifa is only 8.1 miles (13 km) from Morocco across the Strait of Gibraltar. The wind blows here. A lot! Which means warm weather can feel downright cold.

There are two types of wind in Tarifa: the windsurfer-friendly Levante (that comes in from the east, usually warmer and at it’s best during summer) and the Poniente (blowing in from the west, cooler from the ocean and more common during winter), which is best for kite surfers. Due to the force and consistency of windy days, Tarifa has hundreds of wind turbines. Interesting fact: in 2013, Spain was the first country in the world to rely on wind energy as its top energy source. Visiting Tarifa, and experiencing the velocity (and damage) of the wind firsthand, it’s no wonder why.

— Travel-Ling: The winds of Tarifa

Because of wind and location, Tarifa is also a great place to watch fall migration. The bird observation post described at this link is at the pin drop on the map. Zoom the map to see the surrounding area.

We will also take a pelagic tour (see example at Birding the Strait) and go on a whale watch.

Ronda

Point E on the map, 2 nights.

In the province of Malaga, Ronda is at 2,460 ft so its climate is cooler. July high temperatures average 83°F, highs in September are 77°F.

Ronda is known for its cliffside location and a deep canyon that carries the Guadalevín River and divides the town. It is one of the towns and villages that are included in the Sierra de las Nieves National Park.

— Wikipedia: Ronda

The Puento Nuevo bridge is where I hope to see red-billed choughs (Crows With Red Beaks).

Osuna

Point F on the map, 1 night.

Though Osuna is built on a hilltop it is in the Guadalquivir watershed with hot-weather plains below. High temperatures in Osuna average 94°F in July and 85°F in September. Osuna is our last stop before returning home via Seville Airport.

* The bird pictured at top is an immature Spanish eagle coming in for a landing. Our trip checklist has it as the “Spanish imperial eagle.” Birds of the World lists the Spanish eagle and the Imperial eagle as a separate species.