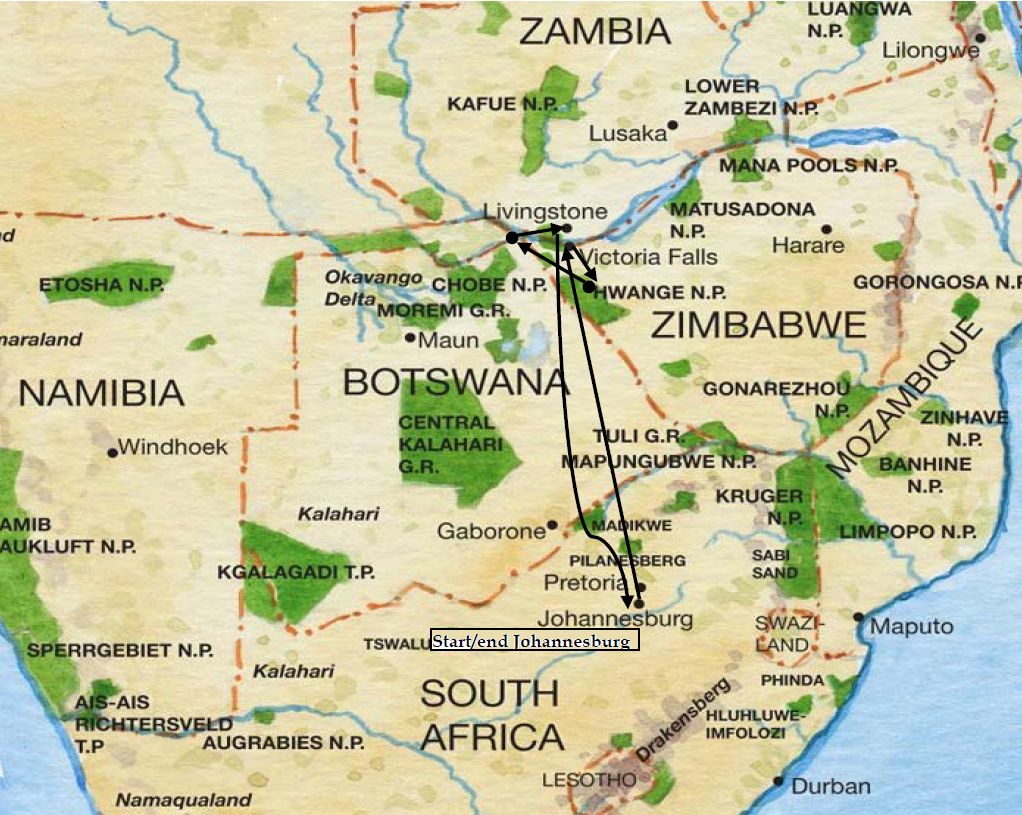

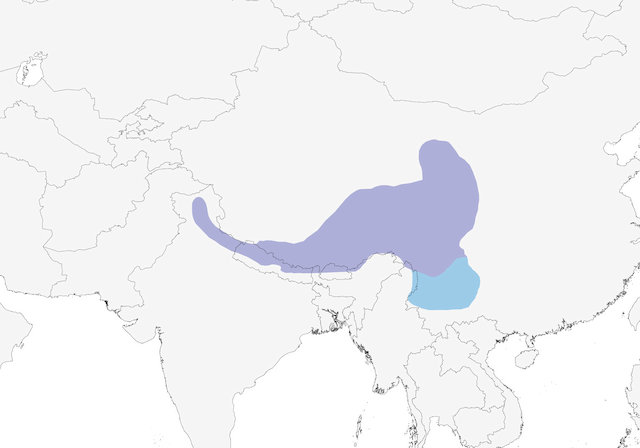

23 January 2024: Day 5, Zambezi National Park — Road Scholar Southern Africa Birding Safari. Click here to see (generally) where I am today.

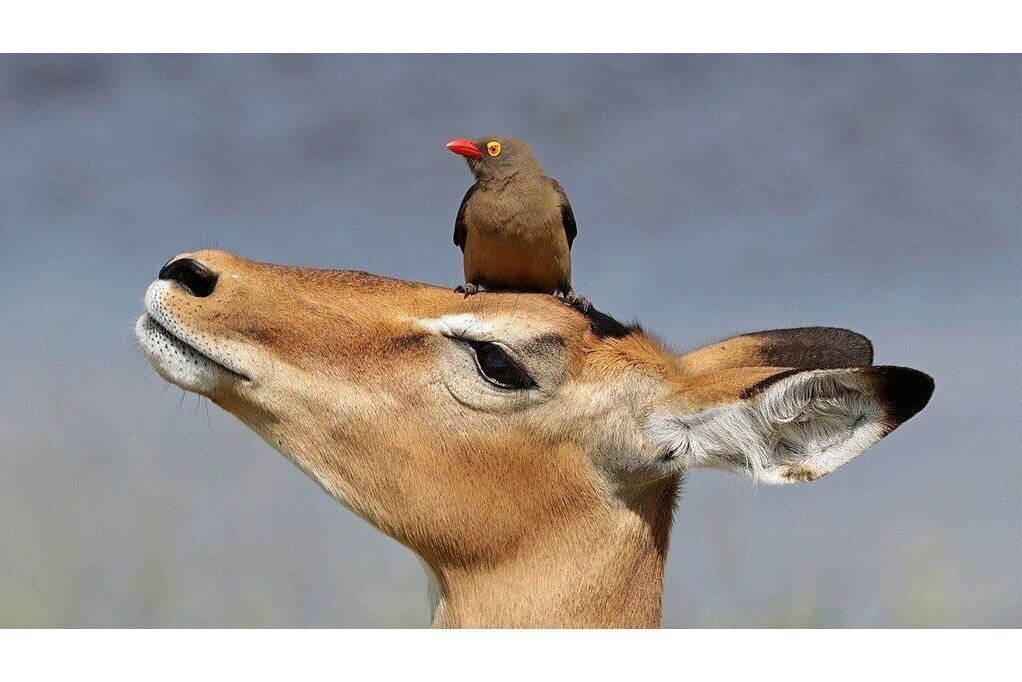

Today we’re on a birding drive through Zambezi National Park where we’re sure to hear the unique call of a very plain bird.

The gray go-away bird (Crinifer concolor) is named for the whiny sound he makes that, in English, sounds like “go awaaaaay.” All gray in color, he has a crest like a northern cardinal but he’s more than twice its length and 10 times its weight. Unlike the cardinal’s beautiful song the go-away bird sounds like he’s whining.

In fact he’s making an alarm call and all the birds and animals know it, fleeing or freezing in place while he warns them.

He whines alone …

… or with a crowd.

Go-away birds don’t fly well but they can clamber.

Though their flight is rather slow and laboured, they can cover long distances. Once in the open tree tops however, they can display the agility which is associated with the Musophagidae [Turacos], as they run along tree limbs and jump from branch to branch. They can form groups and parties numbering even 20 to 30 that move about in search of fruit and insects near the tree tops.

— Wikipedia: grey go-away bird

At some point I’m sure they’ll tell us to “Go Awaaaay!”