21 May 2019

This flowering tree is a native North American but was so rare that few people ever saw it until botanists fell in love with it.

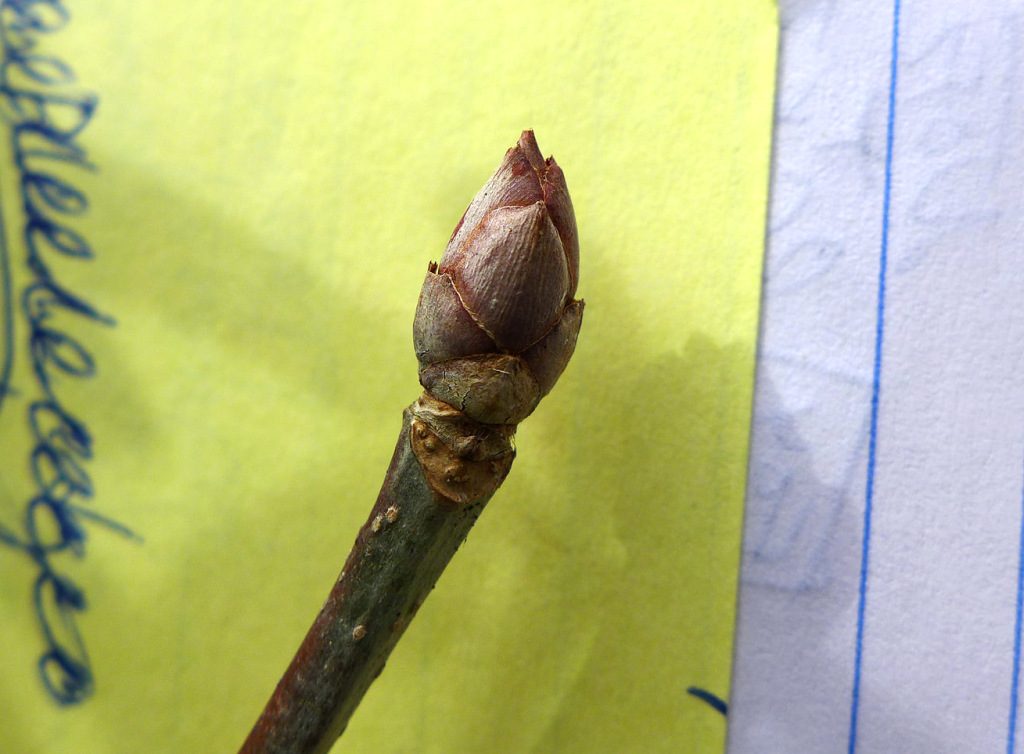

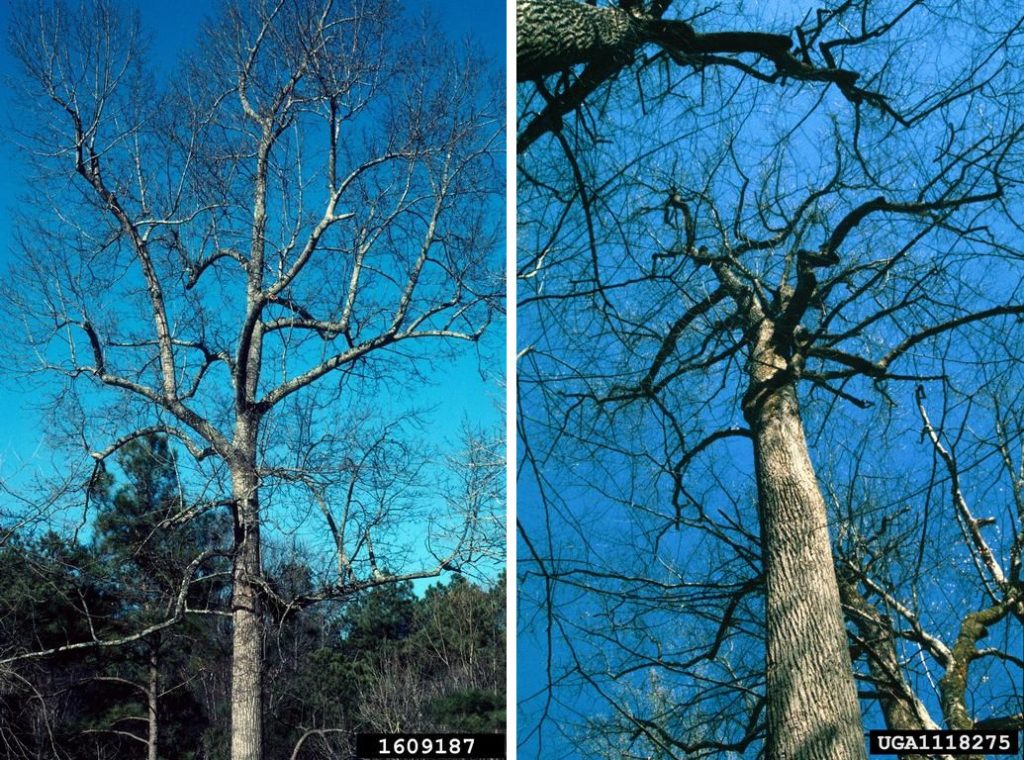

Originally found in small patches from Arkansas to Kentucky and Tennessee, the Kentucky yellowwood’s (Cladrastis kentukea) beautiful flowers, mid-story height, and tolerance for full sun in urban settings makes it the perfect ornamental.

Planted in eastern North America for over 200 years, it became naturalized in scattered locations from Ohio to Massachusetts. Allegheny County is one of the few new places where Kentucky yellowwood grows wild.

On Sunday in Schenley Park, our group was awed by the profusion of vanilla-scented flowers at the Visitors Center. We didn’t recognize the species so I went exploring yesterday and found it both cultivated and wild.

Here are some other cool facts about Kentucky yellowwood:

- It’s called yellowwood because the heartwood is yellow & can produce a clear yellow dye.

- It is the only Cladrastis native to North America.

- The flowers are attractive to bees. Narratives say the tree is attractive to birds.

- Flowering varies from year to year with heavy blooming every 2-3 years, particularly after a long hot summer. 2019 is a big year for Kentucky yellowwood in Pittsburgh.

- Every description says the tree flowers in June, but blooming started here in mid May — two+ weeks early, probably due to climate change.

Once I started looking I found the tree in many out of the way places in Schenley Park, probably growing wild. Kentucky yellowwood is a beautiful success story in Pittsburgh.

(photos by Kate St. John)