Don’t be surprised when you see trees being felled this month at Prospect Drive in Schenley Park. An acre of diseased trees must be clear-cut to protect the park’s healthy oaks.

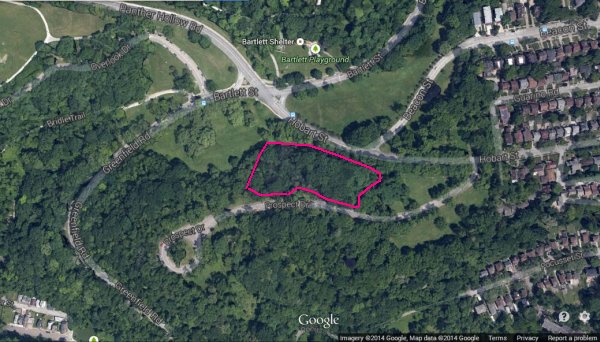

Councilman Corey O’Connor held an informational meeting last night where we learned about the project from City Forester Lisa Ceoffe and Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy’s Erin Copeland. They described oak wilt, its treatment, and the affected area in Schenley Park which I’ve drawn on the tiny map below. Click on the map for a better view in Google.

Here are some of the 55-60 trees that will come down, marked with blue logging paint last summer. Many of them are 100 years old.

Why is the area so large and why must it be clear cut?

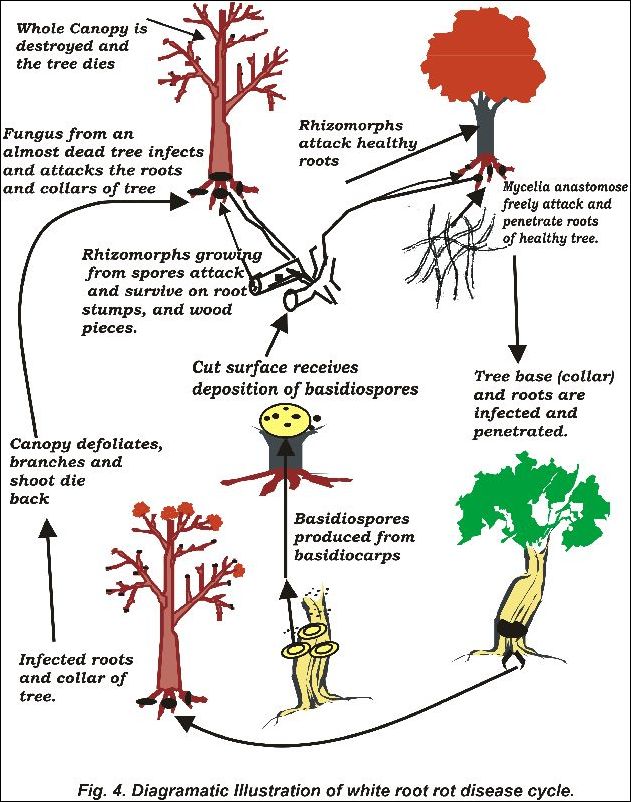

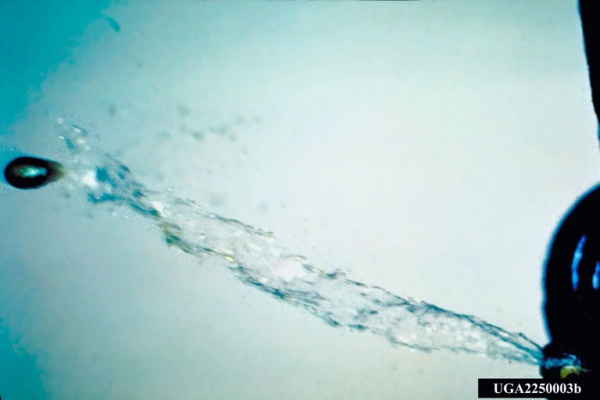

Oak wilt is caused by a fungus that doesn’t spread easily but can kill a tree in 30 days. The fungus travels in the oak’s vascular system and when the tree detects it it blocks those vessels — the arboreal equivalent of a stroke. Watch the 13 minute video here to see how this happens. You know the oaks are sick when you see browning leaves in mid-summer. This is the only sign.

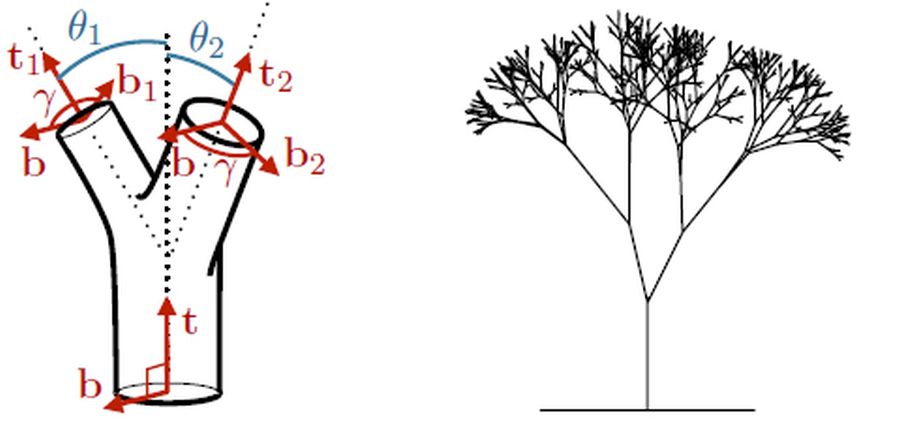

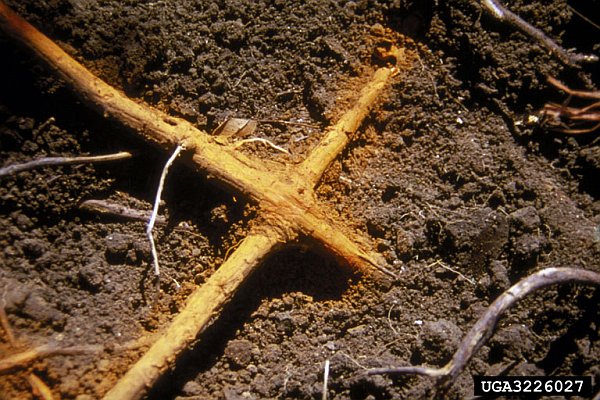

The infection travels through an entire stand because the oaks are joined underground. When their roots touch, they graft to share nutrients and, sadly, disease. We only see the symptoms in summer so a large area can become infected before anyone notices.

Once the fungus has taken hold, an infected tree is doomed. The only way to save nearby healthy trees is to trench the perimeter of the infection(*) and remove all the trees inside the circle. Sap beetles can carry the infection so the logging must be done in winter when the sap isn’t running. (Note! Don’t prune your oaks in spring and summer. This opens them to oak wilt.)

When the logging begins in about 10 days, Prospect Drive will be closed each morning when the equipment arrives and reopened when Davey Tree is done for the day. Signs will be posted explaining what’s going on and Davey Tree will have brochures for those who want to know more. The site is easily visible from the Boulevard so the City expects a lot of questions. Now that you know what’s going on, spread the word.

By the end of February the area will be empty, but not for long. Site restoration begins March 22 with a tree planting conducted by the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy. Who’s going to plant the trees? Volunteers!

Schenley Park needs you on Sunday March 22, 10:00am to 2:00pm, rain or shine. Click here or call 412-682-7275 to learn more about signing up.

(photos from Bugwood.org by Joseph O’Brien, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org and Ronald F. Billings, Texas Forest Service. Screenshot of shared Google map. Click on the map to see details on Google.)

(* Trenching prevents healthy roots from growing into the infected zone.)

UPDATE 2 June 2014: Click here for the most recent update.