27 May 2020

Last evening six of us stood in a dirt parking lot deep in the woods of Washington County and waited for the whip-poor-wills. Twenty minutes after sunset they started to sing.

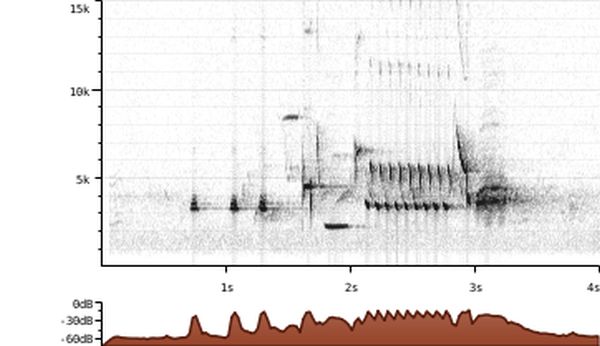

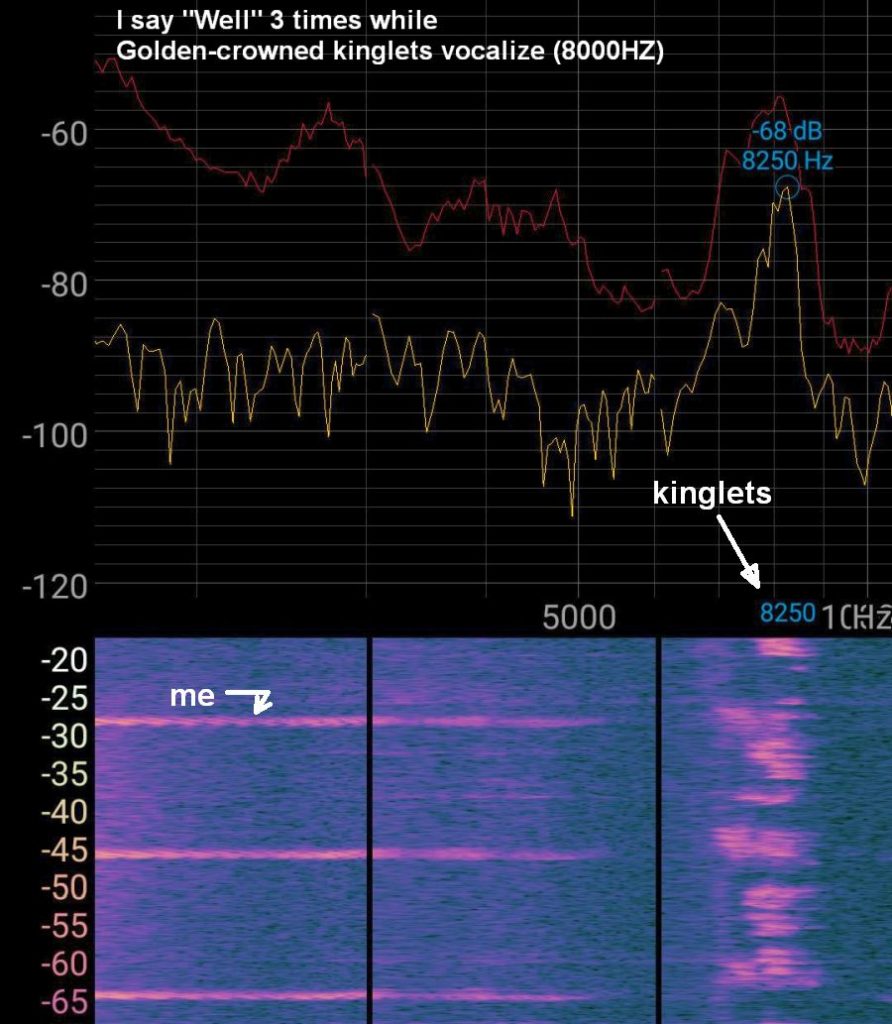

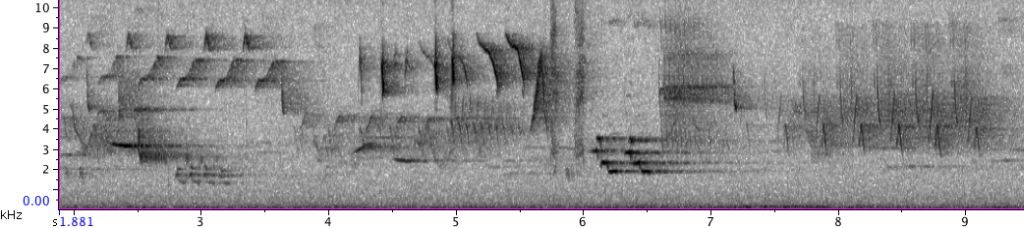

The eastern whip-poor-will says its name: “whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL.” If you’re close enough you can hear the introductory cluck described at Birds Of The World.

Three notes are easily discerned as the bird pronounces its name, and a fourth introductory cluck may be heard at close range.

— Birds Of The World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

We were that close!

Eastern whip-poor-wills prefer dry deciduous or mixed forests with little or no underbrush. Hillman State Park, where we were standing, fits the bill. Hillman is a large former strip mine with no amenities, managed for hunting by the PA Game Commission. The habitat and lack of people appeal to the birds.

When whip-poor-wills nest the female lays two eggs on the ground on top of dry leaves, choosing a place where sunlight makes dappled patterns to match her camouflaged plumage. Hall E. Harrison’s Birds’ Nests Field Guide explains:

Incubating bird sits close; when flushed flies silently away like a moth. Eggs usually discovered by accident rather than by search. Friend of author flushed female from 2 eggs, and returning later to point out nest was unable to find it. After careful study, author detected nearly invisible female incubating 4 ft (1.2 m) away.

— Birds’ Nests Petersen Field Guide by Hall E. Harrison

Since they operate at night even a singing male is hard to find. As we approached our cars to leave, a whip-poor-will sounded very close. Barb Griffith found him in the dark, calling from a flat rock. This photo isn’t the bird we saw, but you get the idea.

Whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL, whip-poor-WILL …

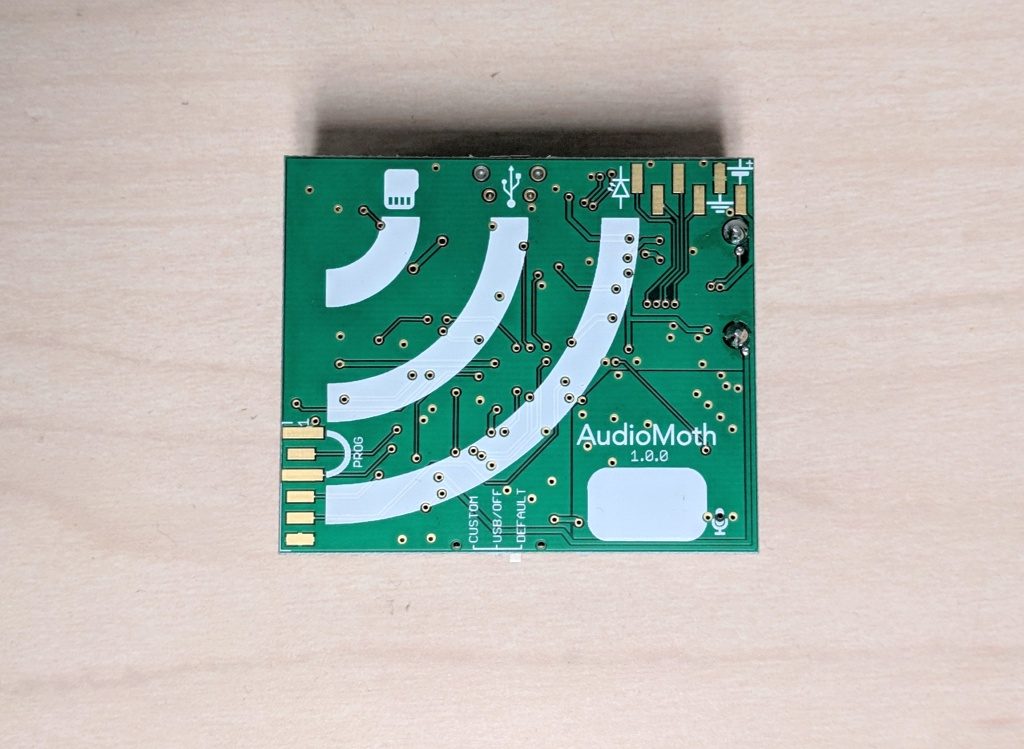

(photos from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals. Audio recording by Kate St. John)