27 February 2022

Much of the coastal U.S. floods during violent ocean storms but some places, like Miami, flood several times a year during high “spring” or “king” tides because of climate-driven sea level rise. This month a new report from NASA and NOAA recalculates how deep the water will be just 30 years from now. It doesn’t look good.

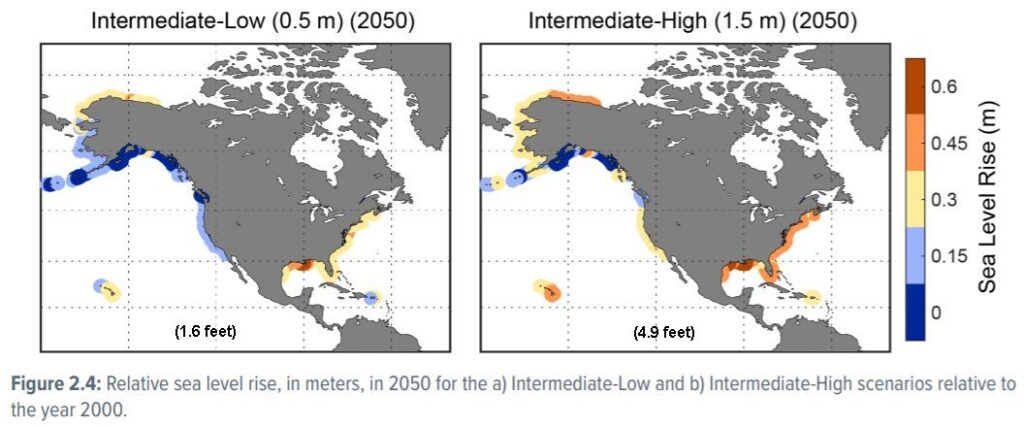

By 2050, the average rise will be 4 to 8 inches along the Pacific, 10 to 14 inches along the Atlantic, and 14 to 18 inches along the Gulf.

— WIRED Magazine: Sea Level Rise Will Be Catastrophic—and Unequal

As Wired Magazine points out, these amounts are averages because water basin topography, water temperature (warmer water takes up more space), land subsidence, and glacial rebound make unique results for each location.

Comparing just two cities on different coasts neatly illustrates what a striking difference these factors can make. Galveston, Texas, where the land is slumping, could see almost 2 feet of rise by the year 2050. Meanwhile, Anchorage, Alaska, could see 8 inches of sea level drop, thanks to the fact that its land is actually rising following the departure of long-gone glaciers.

— WIRED Magazine: Sea Level Rise Will Be Catastrophic—and Unequal

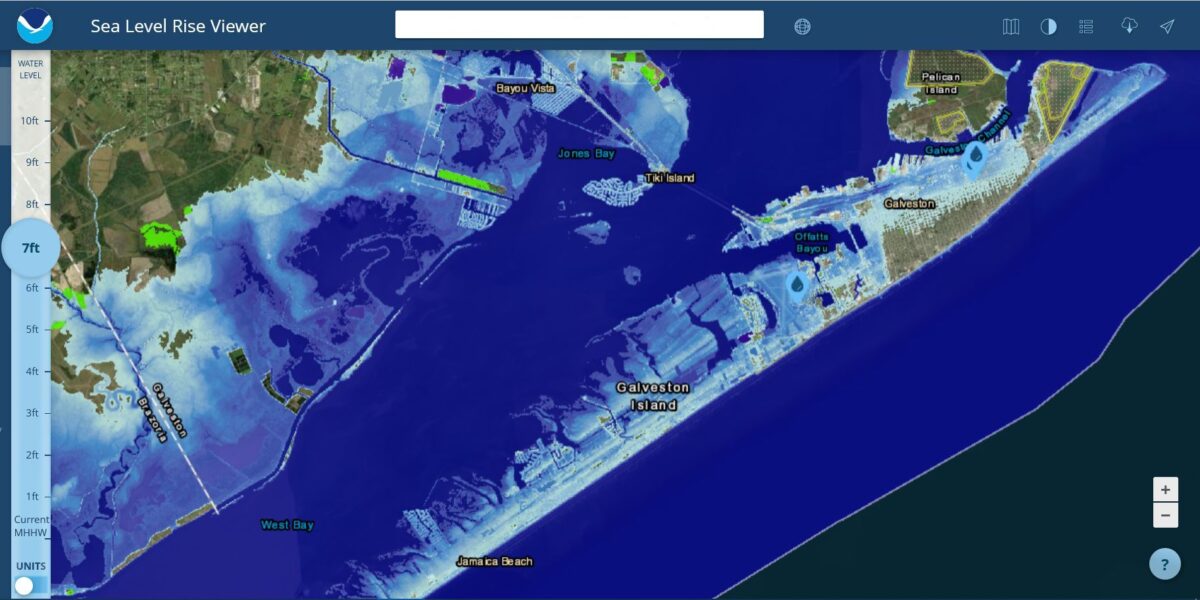

The report indicates that a 2-foot rise is already locked in for 2100 because of past greenhouse gas emissions. If we don’t stop emitting *now* we can expect an additional 1.5 to 5 feet for a total of 3.5 to 7 feet by the end of this century.

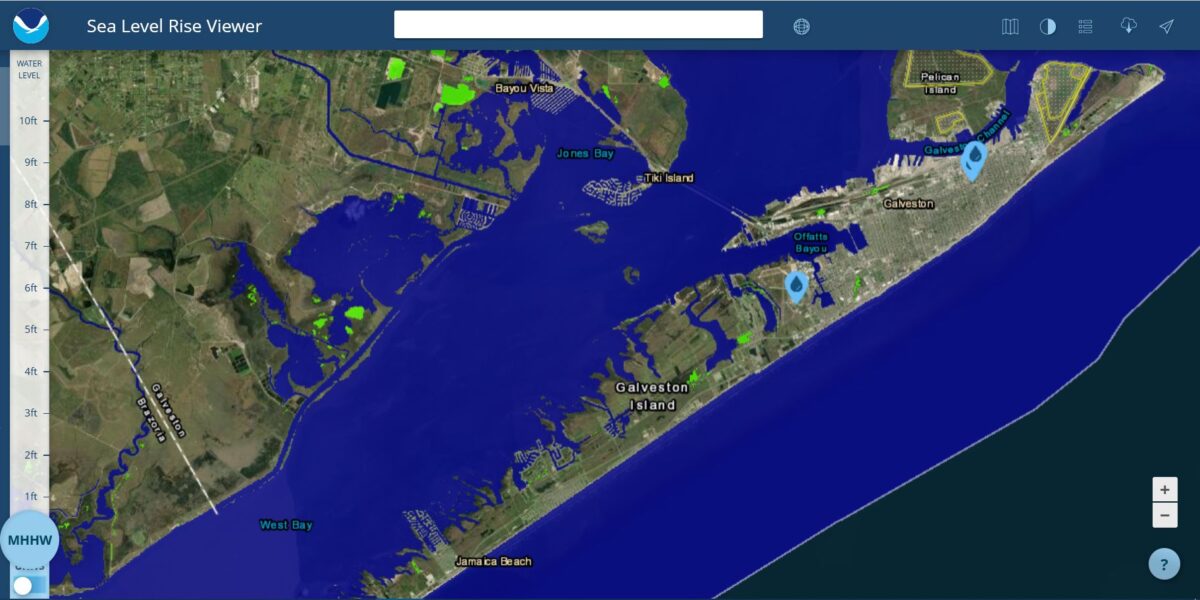

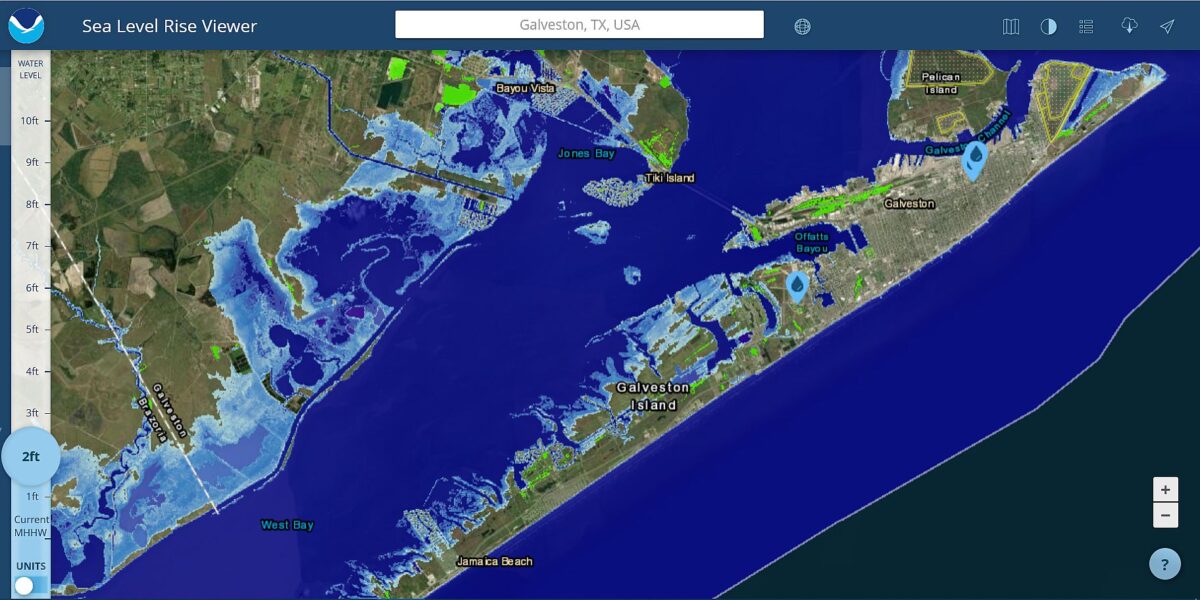

NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer shows Galveston, Texas, below, in three scenarios: current sea level, +2 feet (expected by 2050) and +7 feet (in 2100 if nothing changes). In 30 years Bayou Vista, Tiki Island and Jamaica Beach will be gone. A 7-foot rise by 2100 wipes out most of the area.

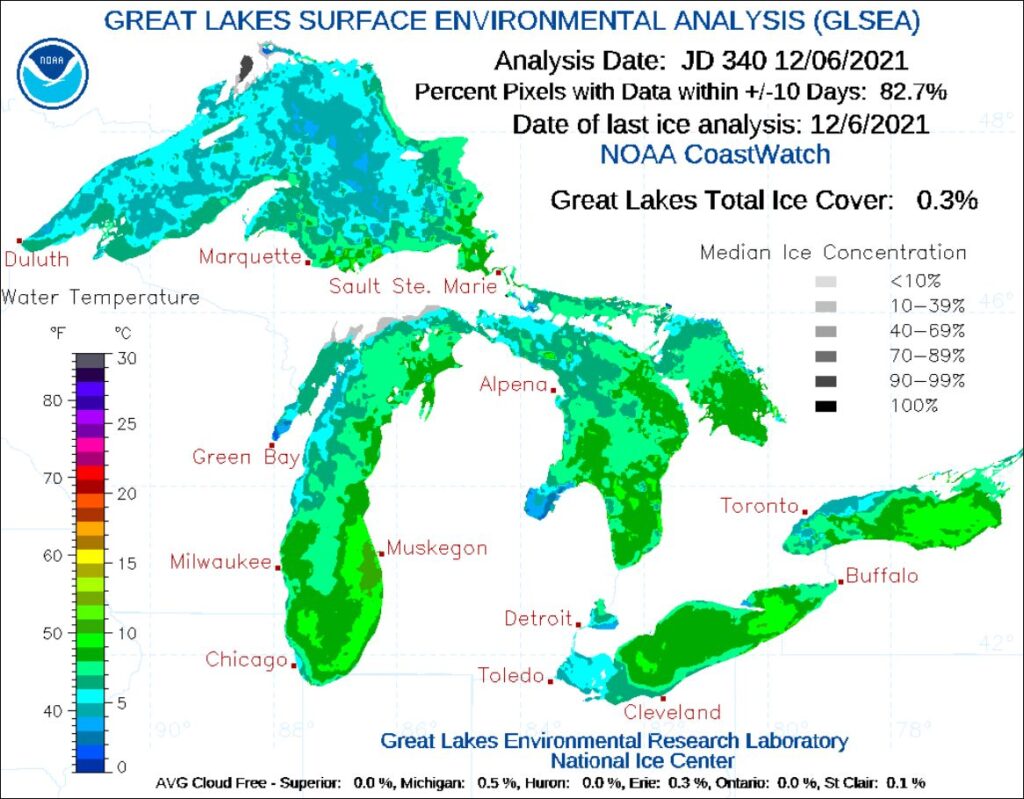

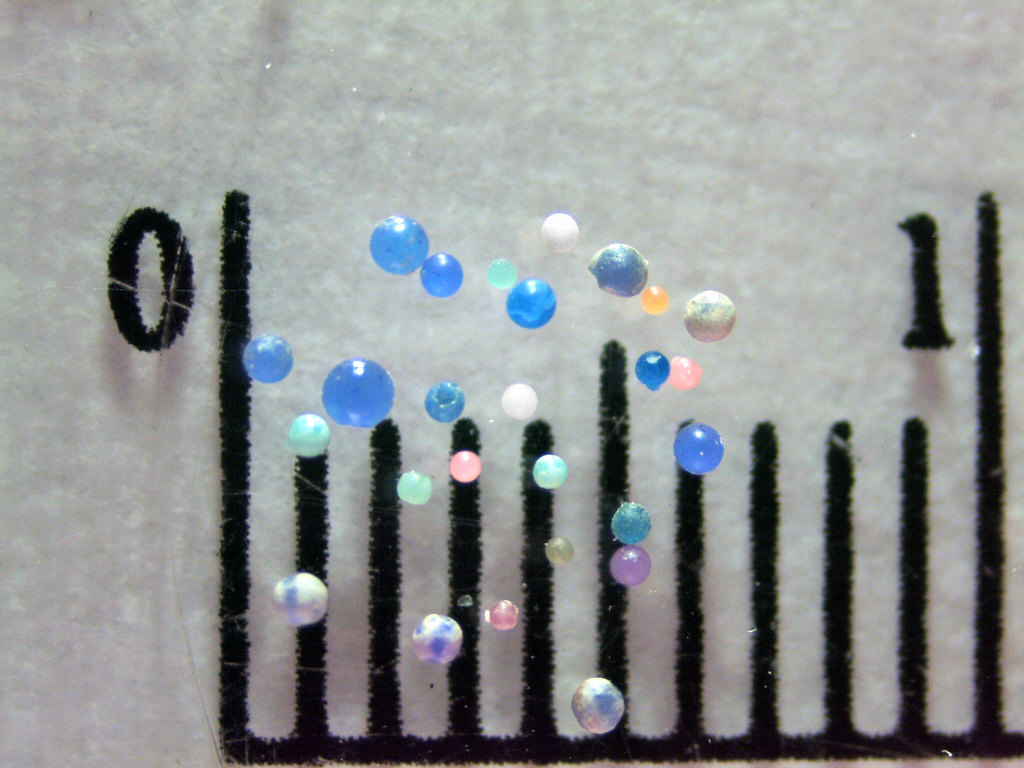

No matter what happens the results will be unequal. Southern Alaska (blue dots) looks good under both scenarios. The Gulf and Atlantic coasts will be in various degrees of trouble.

The report is sobering because it’s unfolding so soon. If you’re 30 years old now, some Gulf Coast places will be gone by the time you’re 60.

Today’s catastrophic flood will be tomorrow’s high tide.

Curious about your favorite coastal places? Look them up on NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Map Viewer.

(images from Wikimedia Commons, NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer and NASA & NOAA’s 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report; click on the captions to see the originals)