27 August 2020

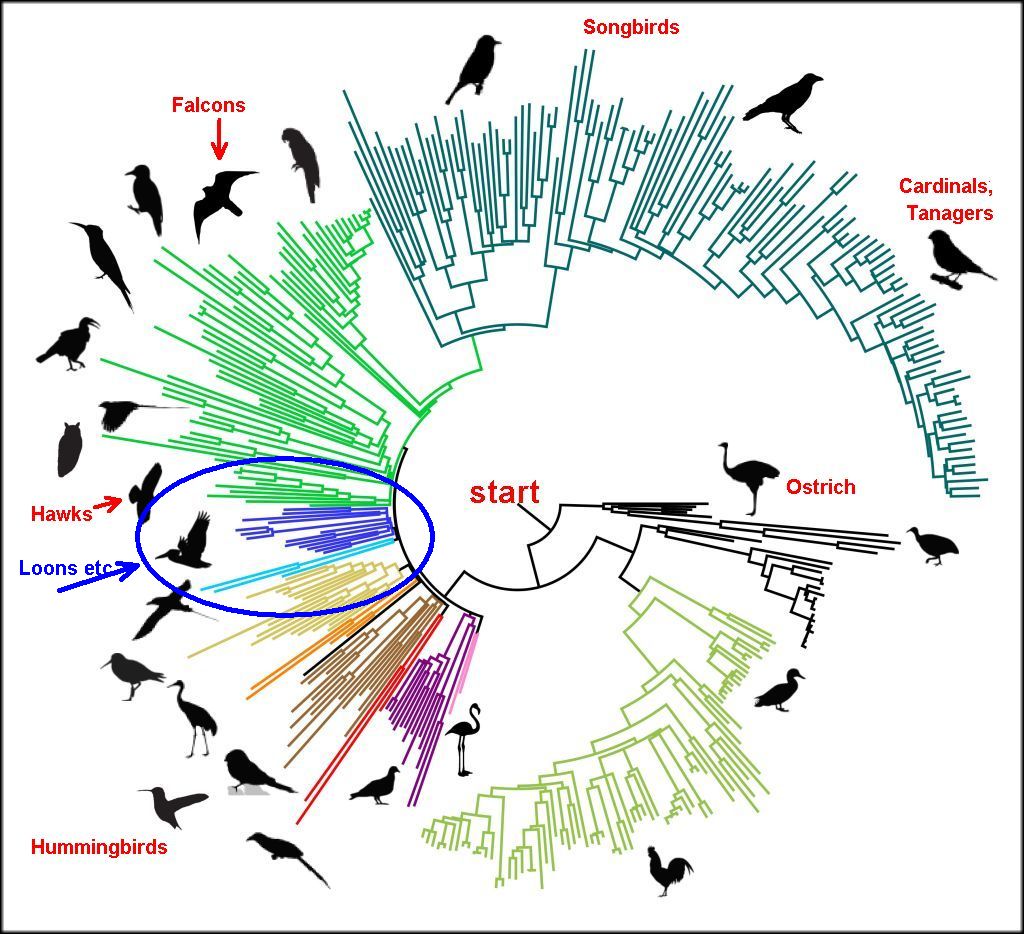

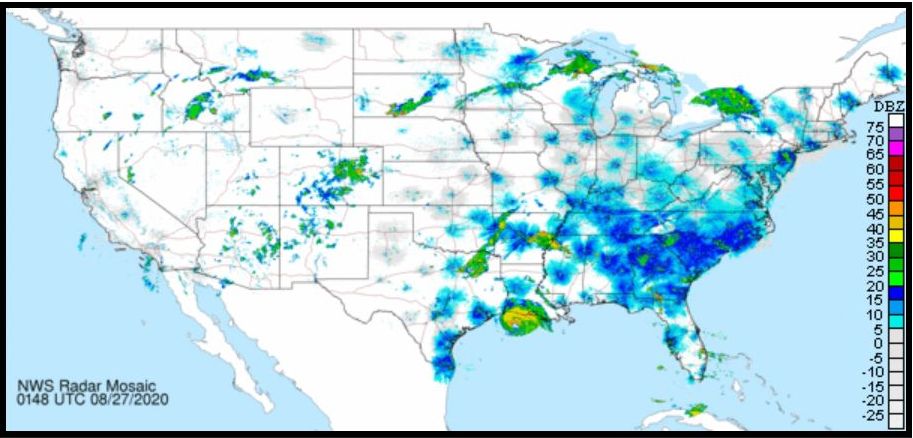

Last night two hours after sunset bird migration was intense over the southeastern United States. The birds showed up as blue blobs on Doppler weather radar but there was a noticeable gap over Louisiana, southern Mississippi and southeastern Alabama. The birds were avoiding Hurricane Laura.

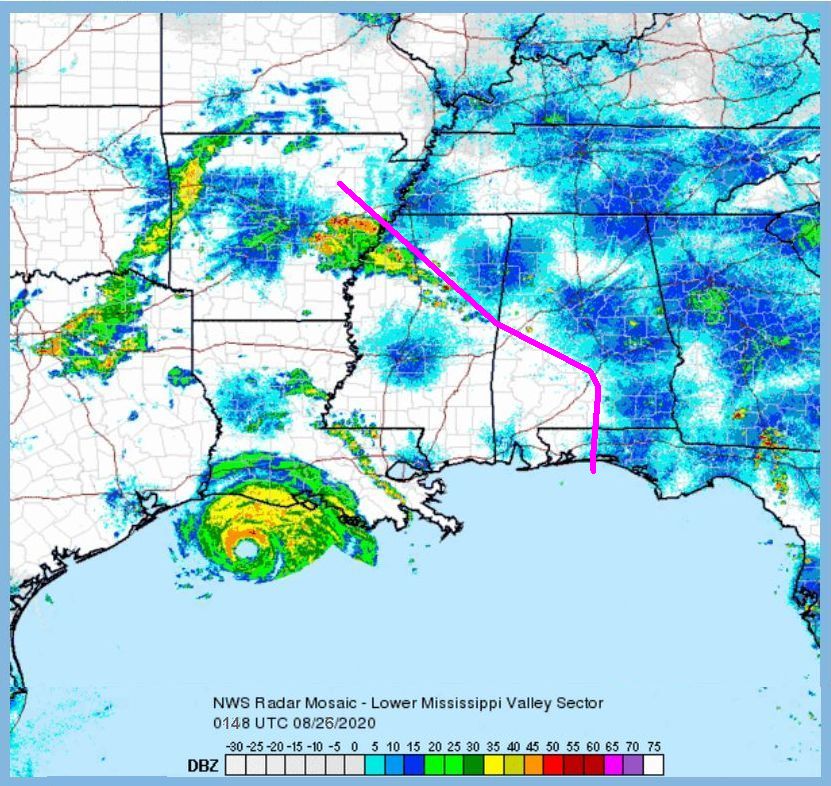

This National Weather Service radar map from 26 Aug 2020, 9:48pm EDT shows where the birds won’t go. (I’ve added a pink line to illustrate their self-imposed boundary.) I believe the small blue blob south of the pink line –at Jackson, Mississippi — is a sign of birds leaving for safer locations.

Humans were urged to leave too because of the coming storm surge, 20 feet high, as illustrated in the Weather Channel video below.

The National Hurricane Center has forecasted “unsurvivable storm surge” from Hurricane #Laura in parts of Louisiana and Texas. Do NOT underestimate this storm.

— The Weather Channel (@weatherchannel) August 26, 2020

This is what that kind of water height looks like: pic.twitter.com/ik7EtpFTzn

As of this writing (27 Aug 2020, 6am) about 150 people chose to stay home in the path of the storm.

Birds don’t have our brains but they know to avoid Hurricane Laura.

(maps from National Weather Service, click on the captions to see the originals; embedded tweet from The Weather Channel)