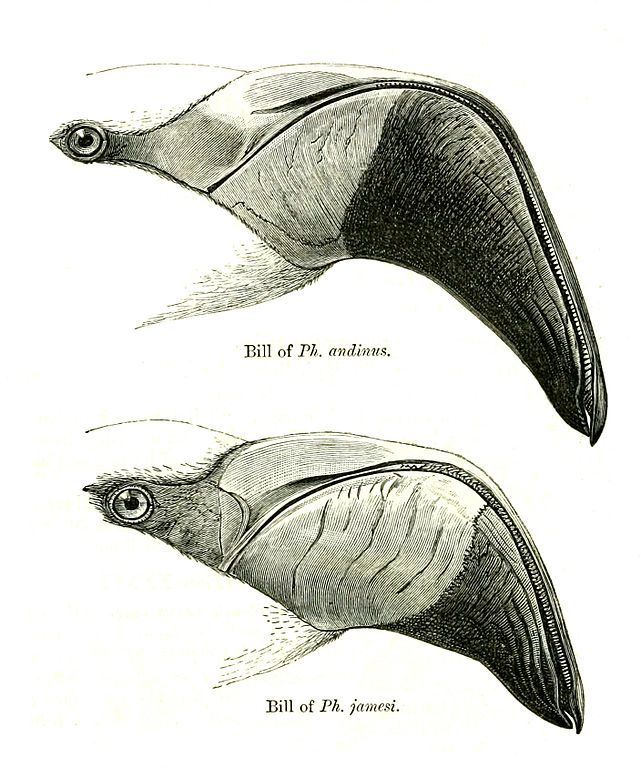

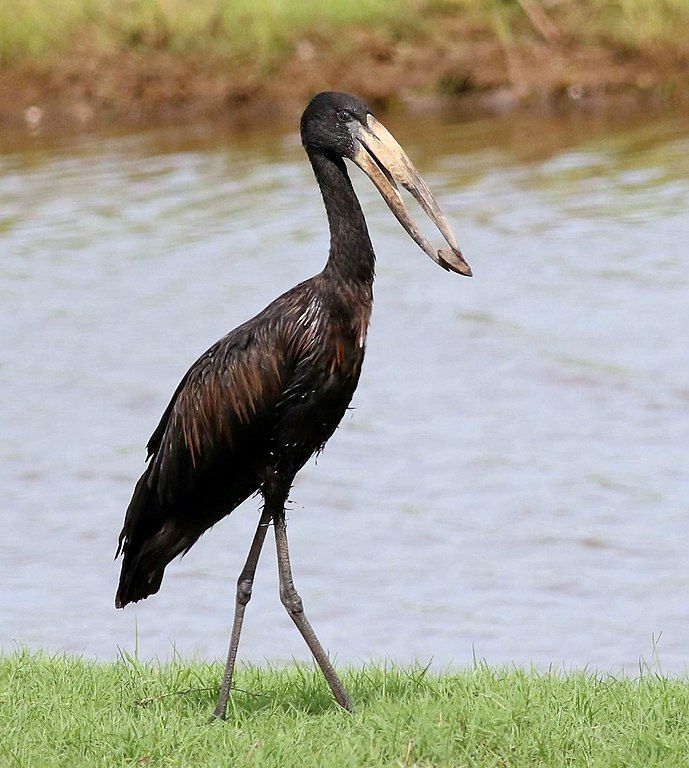

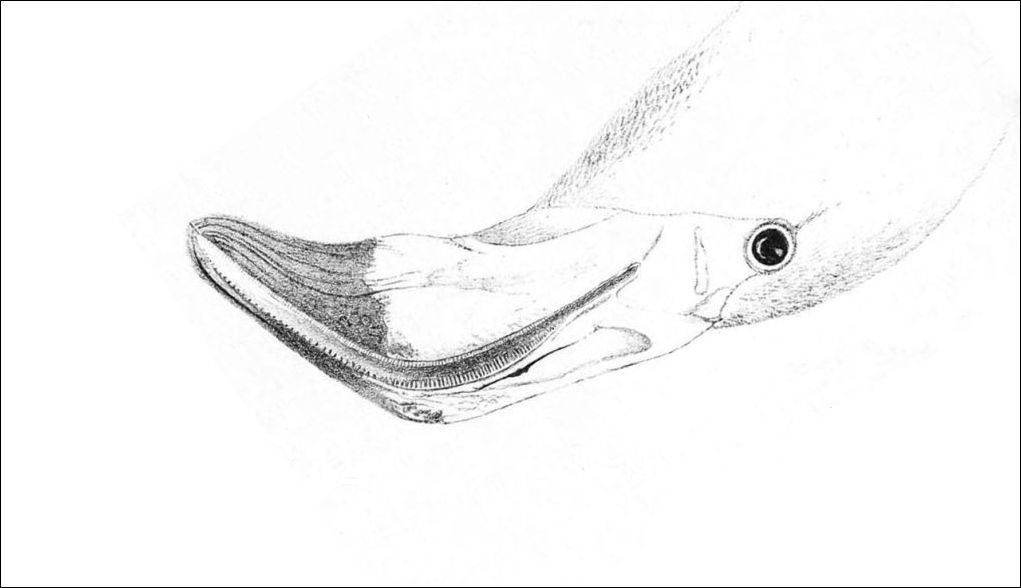

Flamingos’ beaks are quite unusual. Their lower mandibles are larger and stronger than their upper ones and their smiles are upside down.

Their lower jaws are fixed to their heads and their upper jaws move freely. When they open their mouths the top beak moves up like an opening clam shell. This is opposite to us humans. We drop our jaws to open our mouths and take in food.

However, flamingos eat with their heads upside down. In this position they drop their (upper) jaws to open their mouths just like we do. When they’re feeding their smiles are right side up.

Their beaks are designed to catch what they eat. From small crustaceans, mollusks and insects to tiny single-celled plants, their food is suspended in water which they capture by filter feeding, a technique they share with baleen whales and oysters.

Flamingos take water into their mouths and strain it out through the filtering mechanisms in and on the edges their beaks (see illustrations above). When flamingos are feeding rapidly they pump their tongues to suck water in and squish it out. This video from the Galapagos shows how they do it.

That’s why the flamingo’s smile is upside down.

For more information, see this Stanford University article: Flamingo Feeding.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons; click on the captions to see the originals)