24 October 2024

Yesterday I saw a video of a scientist choking up at the prospect of Atlantic Ocean circulation failing. Why is he sad?

Yesterday 44 of the world’s leading climate scientists wrote an open letter about collapse of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation (AMOC)

— Philip Boucher-Hayes (@boucherhayes) October 22, 2024

When I interviewed one of them about the consequences of AMOC reaching a tipping point he could barely keep it together. ? pic.twitter.com/Xsu0po5iZs

(If you don’t see the video above, click on this link.)

The speaker is one of 44 climate scientists who released an open letter this week warning that by 2050 a tipping point will likely cause the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) to fail, making northeastern Europe much colder and ushering in a host of other adverse effects. He is from Britain and 2050 is just 26 years away.

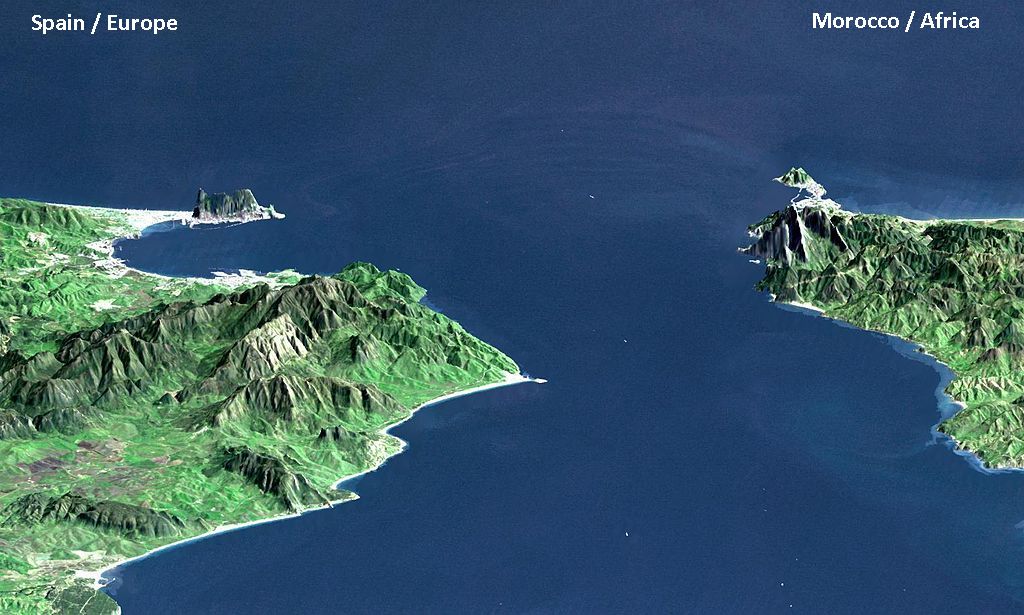

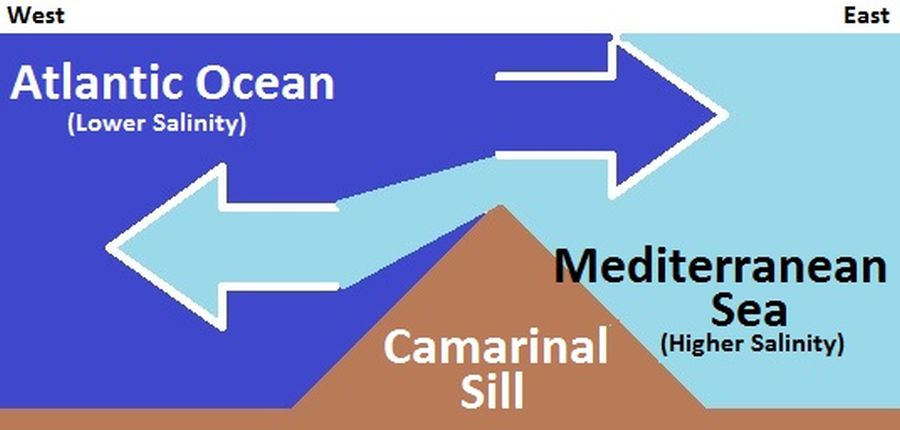

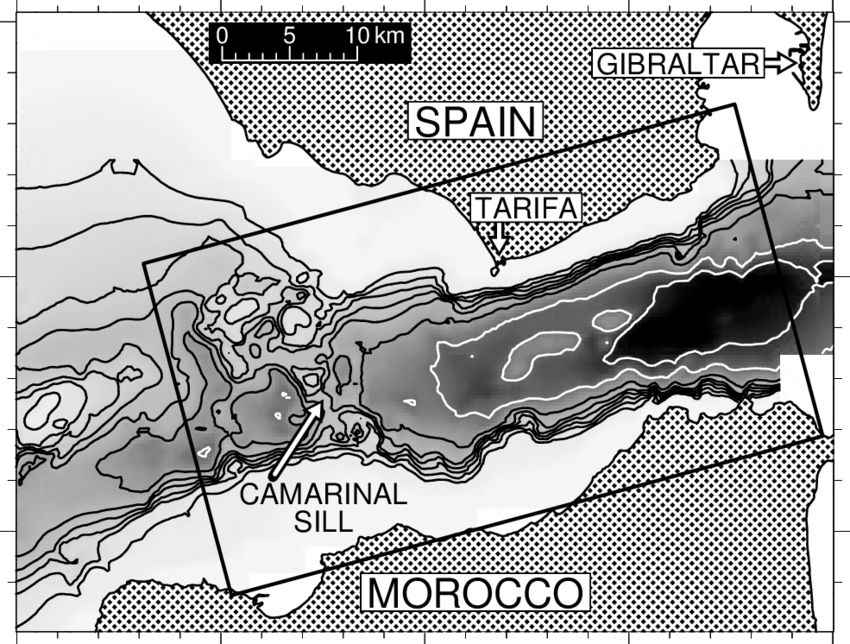

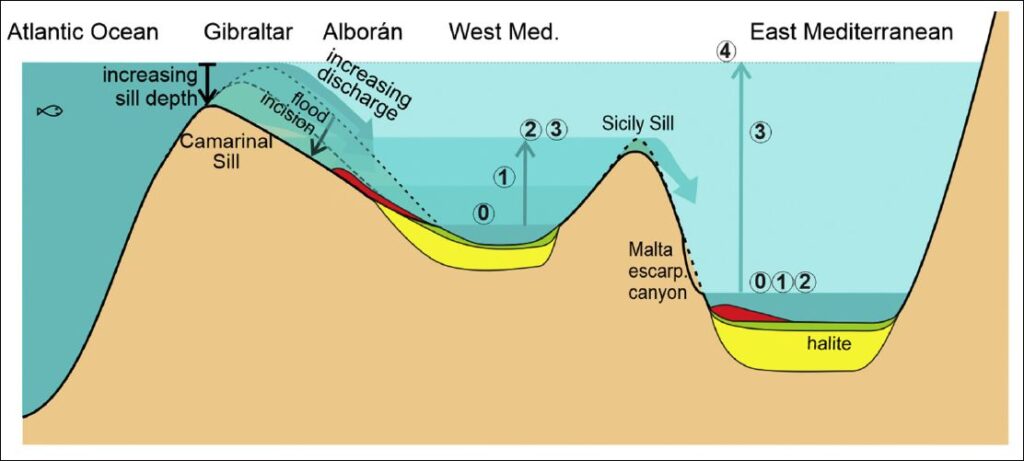

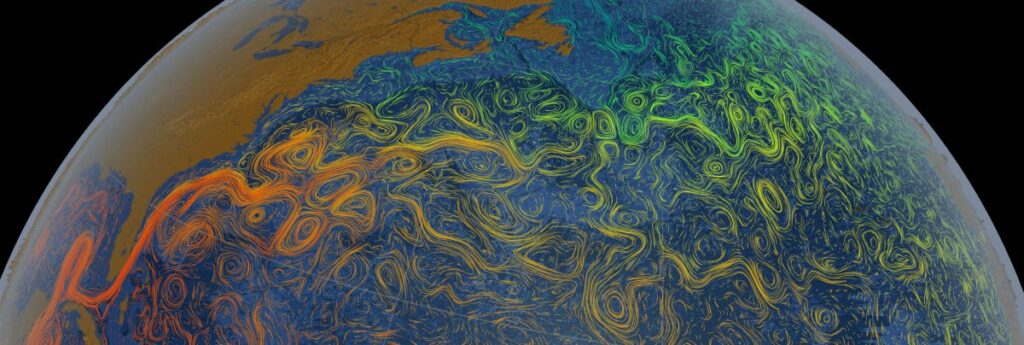

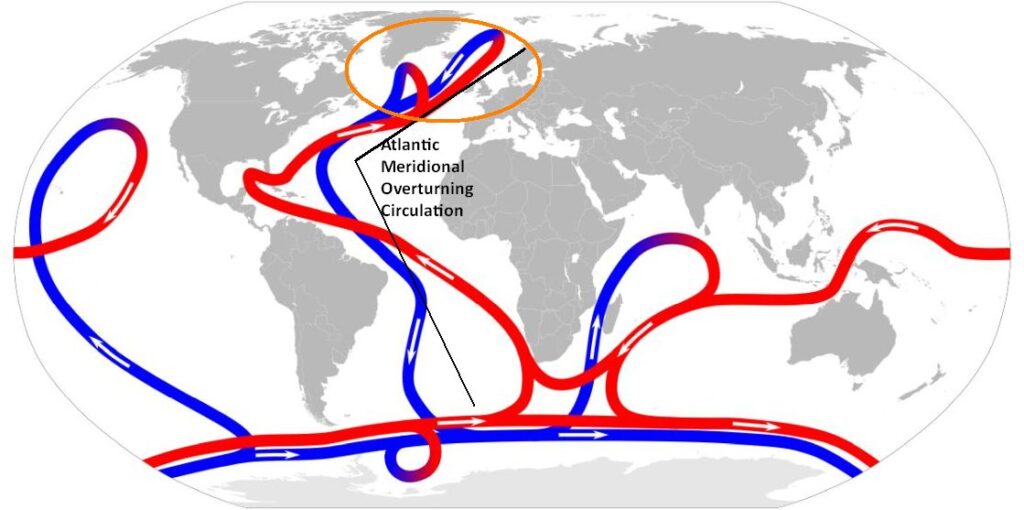

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is the main ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean and a major component of Earth’s ocean circulation. It transports heat and salinity northward and returns cold water to the south. —- paraphrased from Wikipedia

Climate scientists have been studying AMOC for decades because they realize that as Greenland melts, it dumps freshwater into the North Atlantic. The freshwater influx slows the northern end of the AMOC and that messes up the whole system.

We (Americans) haven’t paid much attention to this because we think it will only affect Europe but “messing up the whole system” will change the planet completely. Adverse effects include:

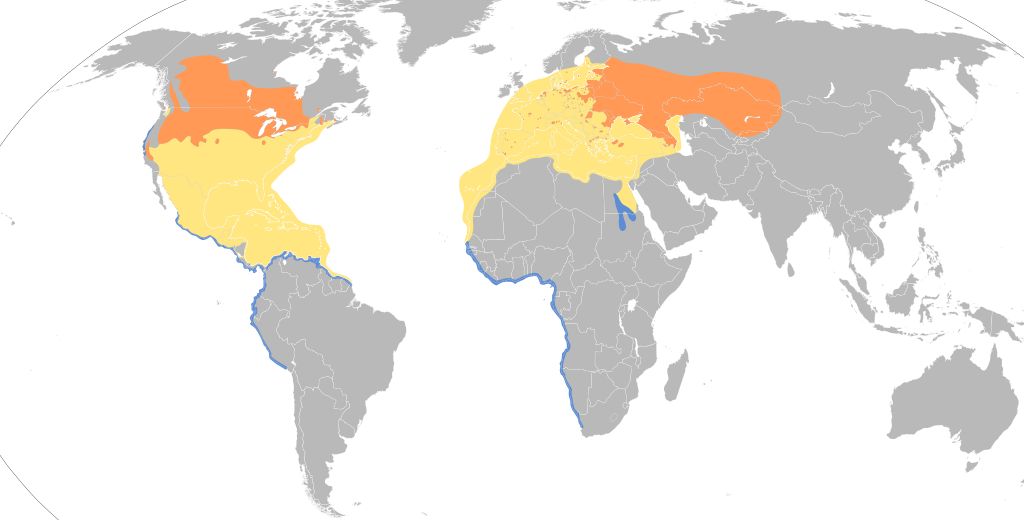

- Northeastern Europe will get much colder

- A new Ice Age will begin so the entire Northern Hemisphere, ourselves included, will get colder. See Warming Up to the Next Ice Age.

- The Gulf Stream won’t transport water away from North America (the far end is chopped off) so, within a matter of years, sea level will rise one-to-three feet on the East Coast.

- The tropical rain belt will move south, disrupting wet and dry seasons in the Amazon and Africa.

This 13-minute video from PBS describes what AMOC is, how it affects us, and what will go wrong when it fails.

For a relatively quick synopsis, see The Guardian: ‘We don’t know where the tipping point is’: climate expert on potential collapse of Atlantic circulation.