4 August 2023

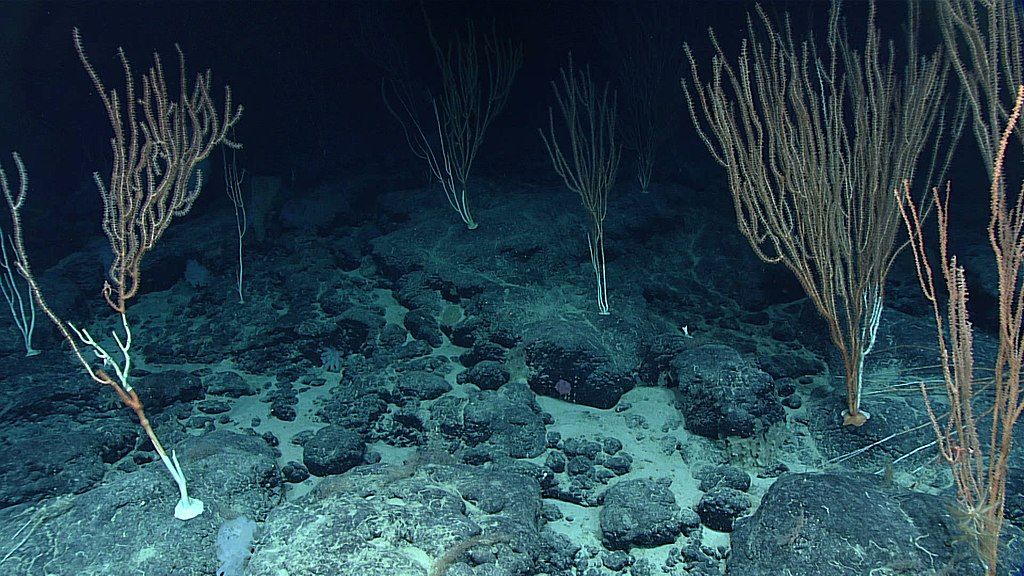

Except for a few scientific probes, we humans know almost nothing about the deep sea, yet remote as it is it contains human evidence. Even in the deepest sea a plastic bag floats by.

It was far too easy to find clips of plastic bags in our #deepsea video footage ?#PlasticFreeJuly pic.twitter.com/8sV9H1GsDT

— Deep Sea Research Centre (@deepseauwa) July 3, 2023

Meanwhile, because the sea floor has no owner, mining companies are chomping at the bit to extract minerals from the deep sea in the absence of any rules to protect it. The companies claim the minerals to be used in electronics would mitigate climate change (really?) but what will the mining damage?

Last month the International Seabed Authority (ISA) met in Jamaica to discuss potential rules to allow deep sea mining. In the end they deferred the decision until next year. This video explains why the topic is so ‘hot’ right now and the potential dangers.

For a lengthy explanation see this 2021 video from the Economist: Mining the deep sea: the true cost to the planet.

(*) The deep sea floor has no “owner” because in international waters it is owned by all of us.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons, tweet and video embedded)