27 November 2022

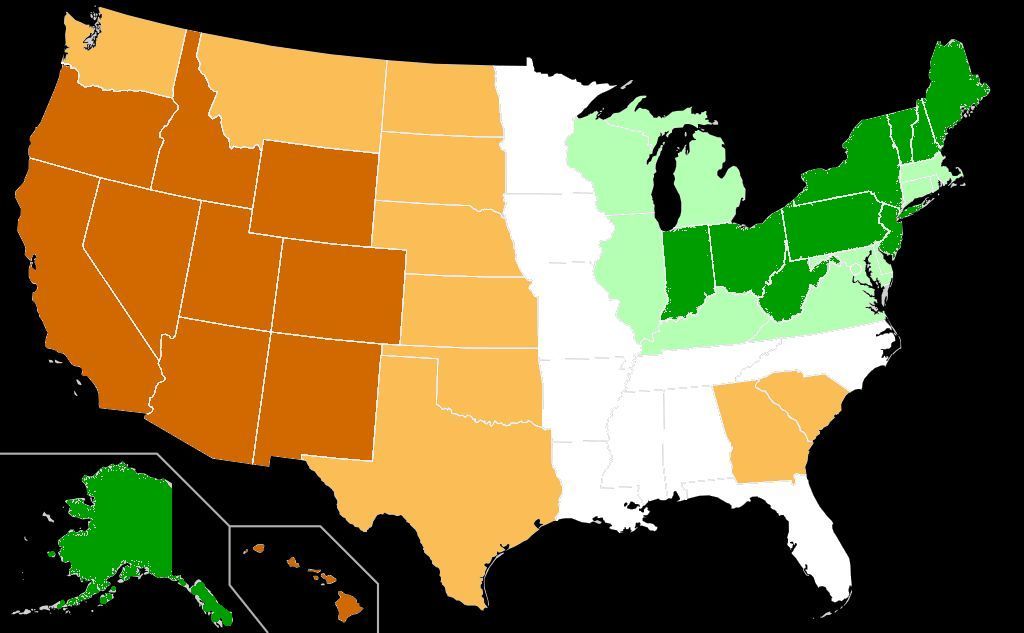

The western U.S. has always been drier than the east but as climate change heats up the planet, drought has become more prevalent. NOAA’s quarterly weather outlooks now include a 3-month drought prediction along with temperature and precipitation forecasts. Some places are more likely to experience drought than others. Which states are more likely? Which are least?

The graphic above is based on Stacker’s article, States With the Worst Droughts, that ranks states by average percentage of land in drought from 2000 to March 2021. Listing the states in order, I grouped them in 10s with darkest Orange indicating the top ten drought states and darkest Green for the 10 wettest. (White = the middle 10)

- The top state for drought is Arizona. No surprise; it’s a desert.

- The state with the least drought is Ohio!

- Georgia and South Carolina stand alone with a lot more drought than their neighbors. Their drought ranking is like Kansas.

- Hawaii (dark orange) and Alaska (dark green) are at opposite extremes.

As climate change continues to unfold human populations will migrate from less habitable to more habitable locations. In the U.S. we can expect people to move west to northeast in the coming century — from more drought to less.

Wondering about your state’s ranking? Click here for the Stacker article.

NOAA’s 2022-23 winter weather outlook is here.

(at top, base map from Wikimedia Commons, precipitation outlook from NOAA; click on the captions to see the originals)