A week ago it was clear that the western edge of Pennsylvania was in a drought and it was likely to get worse.

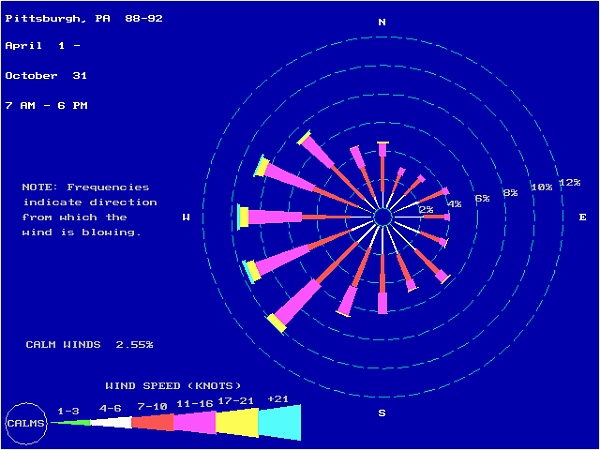

On Thursday July 19, NOAA released its weekly Drought Monitor map and Pennsylvania DEP declared a Drought Watch for 15 western counties including Beaver County where the 90-day rainfall deficit was 5.5″ and Lawrence and Mercer where it was 4.9″. On that day in Pittsburgh our deficit for the past 49 days (June 1) was 3.62″.

The Drought Watch called for a voluntary 5% reduction in water use and puts large water users (industry and water companies) on notice that they should plan for reduced water intake.

The situation was bad.

And then it rained — hard — three days in a row. Almost 2″ of rain fell near the airport July 18-20, probably more than that in the city. The streams in Schenley Park were flowing, the grass turned green, and the ground was muddy. Ah, rain!

But we shouldn’t get too cocky. Technically speaking, we are still under a Drought Watch and there’s reason to keep it that way. Three days of rain may have been a temporary respite.

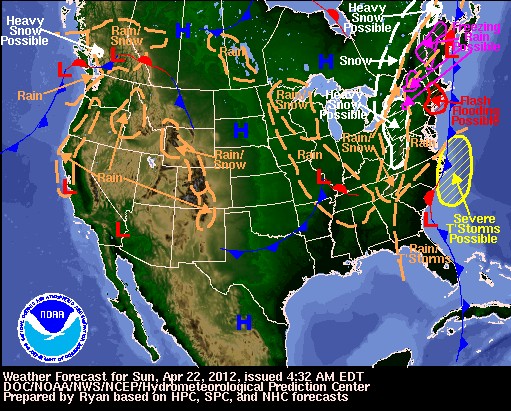

Last Thursday NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center also released the U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for July 19 through October 31, predicting where drought would persist, develop or improve. All of western Pennsylvania and half of West Virginia are slated to become drier in the next three months as shown on the map below.

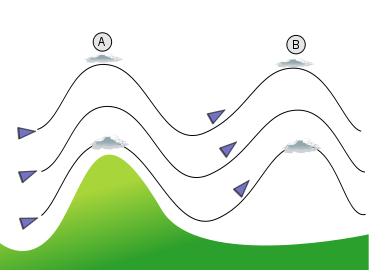

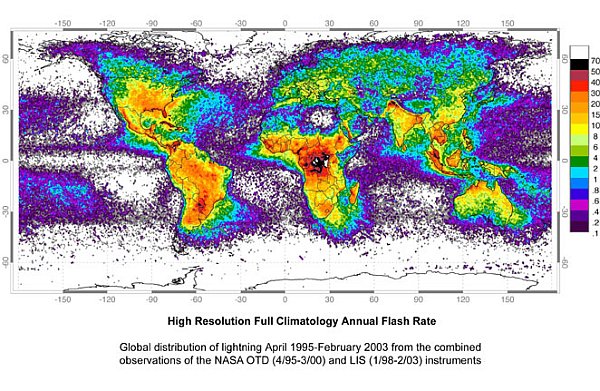

The scary part, as Georgia, Indiana, western Kentucky and the western U.S. know, is that drought breeds drought. When the soil and plants are very dry, there is very little evaporation and transpiration and the dry air “tends to inhibit widespread development of or weaken existing thunderstorm complexes” so the thunderstorms pass us by. According to NOAA’s forecast discussion, “It would require a dramatic shift in the weather pattern to provide significant relief to this drought, and most tools and models do not forecast this.”

So we hope for the best and look for this week’s revised outlook on Thursday.

Meanwhile, when I look at the maps I almost feel survivors’ guilt for having had some rain last week while other parts of the U.S. are suffering.

(images from National Drought Monitor Center and the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center. Click on the images to see their source)

July 24, 1:30pm: Two downpours today! When I write about drought it rains.

Less than a month later, August 16, 2012: The revised drought forecast takes Pennsylvania out of the drought zone. See below.