There’s a page in the Birds of Europe that shows a “curlew” unlike any found in the United States. In fact he’s not related to them.

The Eurasian stone curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus) and his Burhinidae relatives have been hard to classify. They somewhat resemble bustards so were placed in the crane family, Gruiformes, but now they’re with the shorebirds in Charadriiformes. Even so, stone-curlews are far away in the family tree from our curlews, the true sandpipers Scolopacidae.

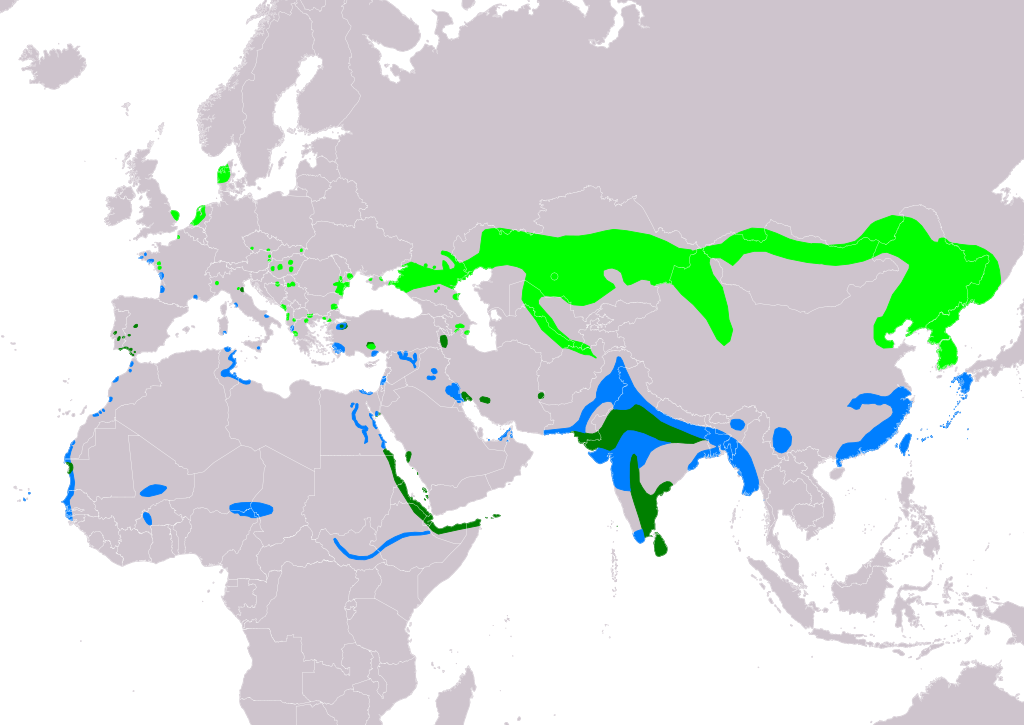

Eurasian stone-curlews breed in dry open places in Europe and spend the winter in Africa. They’re nocturnal birds the size of whimbrels with thick knees and large eyes that look perpetually sleepy. At night the stone curlew sings a loud wailing song.

“Eurasian Stone-curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus)” from xeno-canto by Stanislas Wroza. Genre: Burhinidae.

We have no stone-curlews or thick-knees in the U.S. but they are in our hemisphere. The nearest species lives in Central and South America, the double-striped thick-knee (Burhinus bistriatus).

Photographed northwestern Costa Rica, this bird is showing off his thick knees.

(photos from Wikimedia Commons; click on the images to see the originals)