23 March 2025

Whether it rains or snows, sleets or hails, after the event the National Weather Service can tell you how much precipitation fell in your neighborhood.

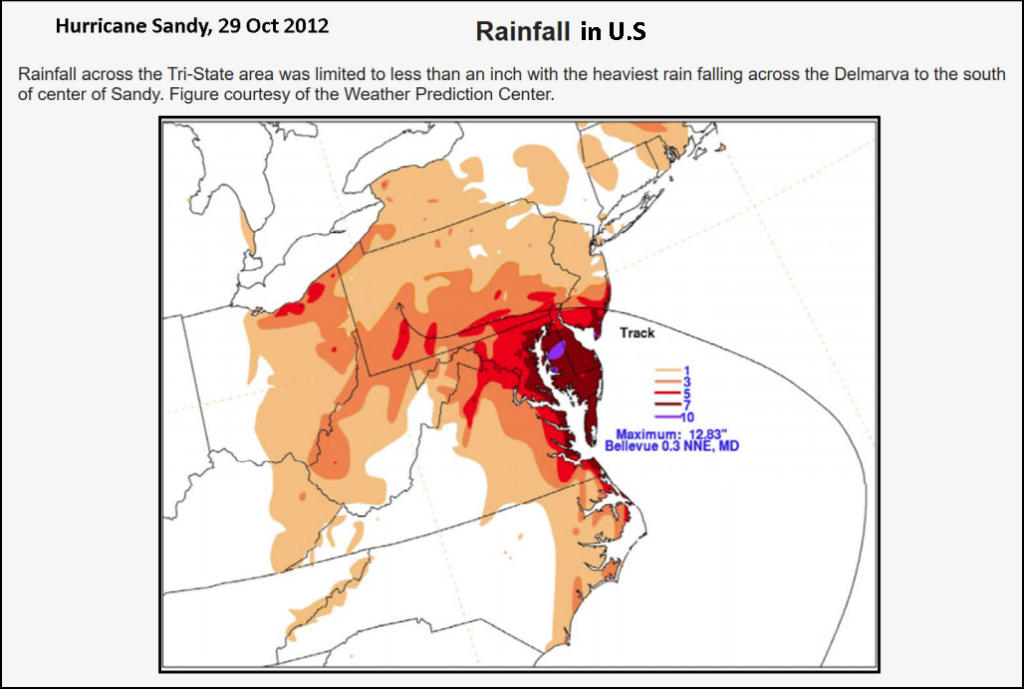

For example, after Hurricane Sandy plowed through Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, New Jersey and Pennsylvania in late October 2012, the National Weather Service (NWS) published this Actual Rainfall map showing a maximum of 12.83″ at Bellevue, Maryland and about 3″ in Pittsburgh.

NWS can do this thanks to radar estimates from airports which are later updated by actual rain gauge readings from official weather stations and from volunteers across the country. The volunteers are members of the Community Collaborative Rain Hail and Snow network or CoCoRaHS.

This month CoCoRaHS is holding their annual Rain Gauge Rally in which each state competes to add new volunteers to the network. As of 11 March the network in Pennsylvania looks likes this. Notice it is heavily populated in some areas but sparse elsewhere. Volunteers needed!

My friend Marianne from DuBois PA joined in 2023 and is encouraging others to join the network this month. She writes:

I have been a CoCoRaHS volunteer since July 2023. This is citizen science that is easy and fun! It is cool that I am able to contribute data to many weather organizations with one daily reading. Even a daily gauge reading of 0 is important, which could indicate drought conditions. Volunteers report their daily observations on the interactive Website or using the CoCoRaHS mobile App. The picture is my rain gauge on Feb. 6, 2025 that has one inch of snow, sleet and freezing rain combined!

— email from Marianne in March 2025

It’s easy to join! Click here and they walk you through the sign-up.

Still curious? This 6-minute YouTube video describes CoCoRaHS and this month’s Rain Gauge Rally. If you want to join, don’t delay. Get in on the Rain Gauge March Madness!

p.s. CoCoRaHS is free to join but you will need a 4” manual rain gauge (or the NWS 8- inch gauge). If you don’t have one, here’s where to get one at weatheryourway.com. (This screenshot does not show the entire page.)