On Throw Back Thursday, a vintage article from 2009:

Small birds have to watch out for danger all the time to avoid being eaten by hawks and cats. But how do they see from every angle?

This goldfinch has …

(photo by Sam Leinhardt)

On Throw Back Thursday, a vintage article from 2009:

Small birds have to watch out for danger all the time to avoid being eaten by hawks and cats. But how do they see from every angle?

This goldfinch has …

(photo by Sam Leinhardt)

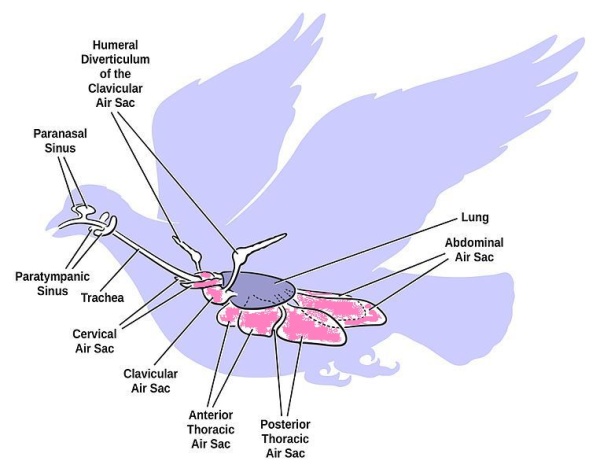

Today, a bird anatomy lesson.

You’ve probably heard the phrase “the canary in the coal mine” and know it refers to advanced warning of a danger. In the centuries before air quality instruments, miners carried canaries in cages into the mines to detect carbon monoxide and methane before they reached dangerous levels for humans.

Why did we use birds to detect bad air? Why not some other small animal?

Birds are uniquely equipped to detect (and succumb!) to bad air because their respiratory systems are so efficient. Here’s why.

Our lungs suck in air, exchange oxygen for carbon dioxide, and push it out. This is slightly inefficient because some air remains in our lungs after we exhale. If you’ve ever had “the wind knocked out of you” you know it feels awful to lose that residual air.

Birds’ lungs don’t expand and contract; they only perform the oxygen-CO2 exchange. Instead birds have 7 to 12 air sacs that act like bellows, moving air in and out of the lungs and the body. The air sacs (pink below) move air in only one direction through the lungs (dark blue below), pushing all of one breath out when the next one comes in. No residual air!

Because the air sacs perform different functions, each air molecule takes 4 steps to pass through the bird’s body –> two in/out breaths.

1st Breath, Air molecule enters the bird.

1. Inhalation: Molecule is sucked into the body by the posterior (back of the bird) air sacs

2. Exhalation: Posterior air sac pushes molecule into bird’s lungs

2nd Breath, Air molecule leaves the bird.

3. Inhalation: Molecule is pulled out of the bird’s lungs by the anterior (front) air sacs

4. Exhalation: Anterior air sac pushes molecule out of the bird!

In this way, birds have more time to absorb oxygen from each breath and their bodies notice airborne poisons sooner than mammals do.

To put it all together, here’s a four and a half minute video that shows how it works.

One more amazing feat: The thin walls of birds’ air sacs can extend into the hollow bones of their wings and legs. They have extra places to store air!

(photo credits: Click on the captions to see the originals in context.

*Station Officer John Scott with canary cage used in coal mines rescue training at Cannock Chase, UK. Image courtesy of the Museum of Cannock Chase. Copyright unknown.

*Bird respiratory system diagram from Wikimedia Commons.

*Video of bird respiration by Ammt Bio on YouTube)

Where do Downtown Pittsburgh’s peregrines spend their time? Lori Maggio found out.

Lori walks to work on Smithfield Street and has a good view of Downtown Pittsburgh along her way. From July 14 through September 30, usually at 7:15am, she recorded the peregrines’ locations whenever she found them. This came to 27 days of observations since Lori didn’t walk every day and the peregrines weren’t always visible.

55% of the time Lori found a peregrine perched on the Lawrence Hall gargoyle at the Boulevard of the Allies facing Smithfield Street, below. This is a very reliable place to find a peregrine falcon if you’re early Downtown.

Most of her other sightings were in the six-block area bounded by Forbes Avenue, Grant Street, the Boulevard of the Allies, and Wood Street. Lori saw a peregrine at the Third Avenue nest site four times and heard the pair e-chupping once. By the way, the Third Avenue nest site is inside that six-block zone.

Here are photos from some of Lori’s recent sightings, September 26-30, 2016.

The roof edge of the Huntington Bank Building:

A window ledge at Huntington Bank:

A porch railing at Lawrence Hall:

And on September 28 when Lori saw a peregrine on the Gulf Tower falconcam, she walked over to take its picture:

Great work, Lori! Now we know where to look for these elusive birds.

(photos by Lori Maggio)

3 October 2016

A study of rock pigeon (Columba livia) brain power indicates they can read four-letter words (*).

Researchers at the University of Otago in New Zealand and Ruhr University in Germany quizzed four pigeons on their orthographic abilities.

According to Science Daily, “In the experiment, pigeons were trained to peck four-letter English words as they came up on a screen, or to instead peck a symbol when a four-letter non-word, such as ‘URSP’ was displayed. … The pigeons correctly identified the new words as words at a rate significantly above chance.”

Eventually the four birds in the experiment recognized 26 to 58 real words and correctly labelled over 8,000 as non-words. They’re the first non-primate species found to have this ability.

So yes, pigeons know when they’re looking at a real 4-letter word but like naïve children they don’t know what it means.

Learn more about the study here in Science Daily.

(photo from Wikimedia Commons. Click on the image to see the original)

(*) Since pigeons have no reading comprehension, they can’t actually read.

Last weekend Bob Machesney and Mike Fialkovich were hiking near Slippery Rock Creek in Lawrence County when Bob found some unusual flowers growing on a gravel heap.

Mike knows a lot about plants but these flowers were new to him so he took some pictures — the first two photos shown here — while Bob collected an identification sample for his wife, Dianne.

Dianne identified the plant as wild mignonette (Reseda lutea) and Bonnie Isaac, Botany Collection Manager at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, confirmed that this is indeed a rare find in western Pennsylvania. It’s a County Record for Lawrence County.

Resada lutea is a biennial or short-lived perennial native to Eurasia that grows in well-drained chalk or limestone soils. It can spread by root cuttings or seed but it won’t start to grow until the soil is disturbed. At full height the plant is one to two feet tall.

Blooming from June through September, the flowers have unusual shapes as you can see in this Wikimedia close-up.

Wild mignonette is rare in western Pennsylvania because we don’t have well-drained limestone soil.

It found a home on a gravel heap in Lawrence County, the only well-drained limestone for miles.

(photos by Mike Fialkovich. Closeup from Wikimedia Commons; click on the image to see the original)

1 October 2016

If it’s clear tonight in Pittsburgh you’ll be able to see the International Space Station (ISS) traverse the sky for six minutes.

At 7:41pm the ISS will appear in the southwest and pass directly overhead on its way northeast at 17,150 miles per hour. At five miles per second it doesn’t take long to disappear. Read more here in the Post-Gazette on what and where to look for it.

You don’t have to be in southwestern Pennsylvania to see it. NASA’s Spot The Station website predicts ISS’s appearances around the world.

Armed with this information you can impress your friends. Casually looking at the night sky you can say, “Look over there. In half a minute the International Space Station will appear on the horizon and pass directly overhead.”

A fast-moving shiny thing in the sky.

(photo of the International Space Station as seen from the Space Shuttle Atlantis, 19 July 2011. Click on the image to see the original)

p.s. Unless they’ve already fixed it, I believe there’s a typo in the Post-Gazette’s 2nd paragraph which says “Monday” but probably means Saturday.

THE BLACK MOON MADE ME FORGET SOMETHING I ALREADY KNEW. BIG CORRECTION AT 10:45AM! We never see the dark side of the moon except from outer space. Thank you, Tom Hoffman, for reminding me. (Shaking fist at Black Moon!)

30 September 2016: Today the media is peppered with the ominous words “Black Moon.” Here’s what that’s all about.

By the time you read this the moon has already risen in Pittsburgh at 6:46am. It came up half an hour before sunrise, will reach its zenith at 1:00pm, and will set at 7:07pm four minutes after sunset. It’s in lock step with the sun.

But we won’t see it.

It’s a new moon traveling so close to the sun that the sun’s glare hides it. And it’s not illuminated. It is back lit by the sun.

This is the second new moon this month, the so-called “Black Moon.” Like its bright twin, the Blue Moon, two of these in a month are a relatively rare occurrence. The last Black one was 32 months ago.

What about the dark side of the moon. Is it always black?

No. Today’s Black Moon is sunlit on the other side. But if we could see it, it would look unfamiliar.

During the new moon last July, the dark side of the moon was facing the DSCOVER satellite when NASA’s EPIC camera recorded time lapse photos. Watch as the dark side flies by the southern hemisphere. Doesn’t it look odd!

For starters, it’s darker than we expect. Even when fully illuminated the moon is darker than Earth from outer space because it reflects less light. Our planet is bright blue and white because it has lots of water. The moon is dry and dark. It matches the color of Australia.

Here’s the dark side in a still photo from August 2015.

Look closely and you’ll see that it’s missing the craters we always see.

Of course we shouldn’t expect the dark side to match the bright side. But the fact that it looks so different makes this Black Moon unsettling. 😉

(New moon symbol from Wikimedia Commons. Moon and earth animation from NASA. Click on the images to see the originals.)

On Throw Back Thursday:

How many house sparrows equal a common grackle? Find out in this September 2009 article …

28 September 2016

Right now it’s flu shot season, soon to be followed by flu season itself from December to March.

Wild birds have been blamed as a source of influenza but new evidence indicates they’re not the cause of bad flu. To understand why here’s a primer on where flu comes from, how it spreads, and why flu season is in the winter.

Where does flu come from?

Other people! It spreads best — and quickly creates new strains — where people are densely crowded. Amazingly, the Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 spread quickly because of crowded camps and trenches in World War I. A new study this month from the University of Chicago finds that “surveillance for developing new, seasonal vaccines should be focused on areas of east, south and southeast Asia where population size and community dynamics can increase transmission of endemic strains of the flu.” Click here to read why flu does so well in that part of the world.

How does flu spread? In the air. We breathe it in. Airborne transmission actually explains …

Why is flu season in the winter?

Not too long ago we were told that it’s in the winter because migratory waterfowl pass avian flu to domestic birds during fall migration. Wrong!!

Recent studies of avian flu transmission show that it spreads in poultry factory farms (crowded conditions!) and along our poultry trade routes. It follows our poultry, not wild birds’ migratory paths.

And the timing has nothing to do with migration. Flu season is in the winter because the pathogen stays airborne longer in dry winter air. It falls to the ground in summer humidity.

So why are waterfowl off the hook?

Wild birds aren’t spreading the worst strains of avian flu because they don’t have it.

After the H5 avian influenza A virus hit U.S. poultry farms in 2014-15, officials worried that avian flu would return when waterfowl migrated south again … but it didn’t. The reason was found by researchers from St.Jude Children’s Research Hospital who “analyzed throat swabs and biological samples taken from 22,892 wild ducks and other aquatic birds collected before, during and after a 2014-15 H5 flu outbreak in poultry.”(*) None of the birds had the highly pathogenic influenza A virus.

“Bad flu is not our fault,” say the ducks.

Read more here at: Evidence suggests migratory birds are not a reservoir for highly pathogenic flu viruses.

p.s. Remember to get a flu shot! However, if you’re over 65 immunologist Laura Haynes says you should get it after Halloween if you can. Click here to read her advice on NPR.

(photo by Brian Herman)

Here’s a bird you’ll never see in Pennsylvania.

The spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) is a resident of the northern forest in Canada, Maine, Minnesota and the northern Rockies. Though he resembles our state bird, the ruffed grouse, his diet keeps him north of us.

In winter our ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) eats buds, twigs, catkins, ferns and fruit — easy food to find in Pennsylvania.

Not so the spruce grouse. His winter diet is conifer needles. They’re so hard to digest and he has to eat so many of them to stay alive that his digestive system changes in the fall. According to Cornell’s All About Birds, his “gizzard grows by about 75 percent, and other sections of the digestive tract increase in length by about 40 percent.” Before the snow falls he stocks up on grit so his gizzard can grind up the needles.

In September 2012 Sparky Stensaas found this spruce grouse swallowing road grit and feasting on a tamarack in northern Minnesota. Tamaracks loose their needles in October so the grouse had to eat them right away.

This bird eats spruce needles, too. That’s why he’s a spruce grouse.

Click here to see the video full screen and read Sparky’s description of what this grouse was up to.

(video by Sparky Stensaas)

* Tamaracks are larches, deciduous conifers whose needles turn yellow and drop in the fall.