10 January 2017

What good is a museum collection of bird eggs? In the case of peregrine falcons, museum egg collections helped save the species.

After World War II new organochlorine insecticides were introduced on the open market and widely used in agriculture. The seed dressings (coatings) of dieldrin, aldrin and heptachlor instantly killed birds as they fed in the fields. DDT was more insidious. It accumulated in the body and slowly wreaked havoc.

By the mid 1960s, seed dressings were already banned in Britain but the peregrine population was still crashing and Derek Ratcliffe wondered if something else was going on. Since 1951 he and other peregrine monitors had seen many broken eggs in eyries and frequent nest failure. Ratcliffe wondered if peregrine eggs were collapsing because the eggshells were thin. He decided to find out.

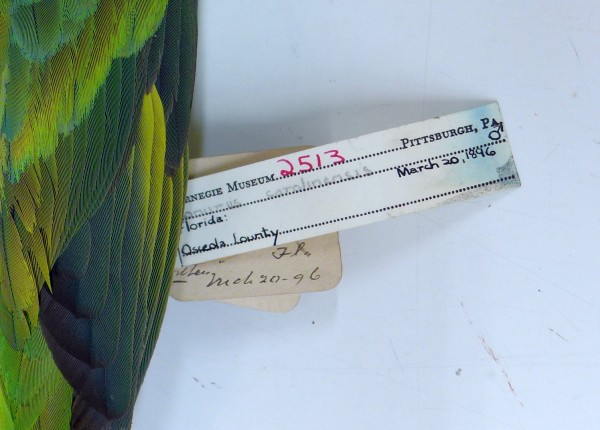

The eggs in museum collections are empty shells (notice the tiny drill hole in each specimen above) and you must not break them to measure the shell’s thickness. However the weight of the shell correlates to thickness if you account for the size of the egg. Ratcliffe weighed each egg and measured its length and width. Then he used this formula to determine its thickness index.

Shell thickness index = Weight of eggshell (mg) / [Length (mm) * Breadth (mm)]

For his preliminary study, Ratcliffe measured egg specimens in the British Museum of Natural History and 30 eggs collected in more recent peregrine surveys. Indeed the shells had thinned since World War II, prompting further research.

Ratcliffe’s final study published in 1967, Decrease in Eggshell Weight in Certain Birds of Prey, showed that the turning point in Britain was in 1947. Prior to that shell thickness averaged a steady 1.82 for over 125 years. After 1947 the thickness dropped to 1.53, an average loss of 16%. Later studies showed trace amounts of DDE(*) in the shells.

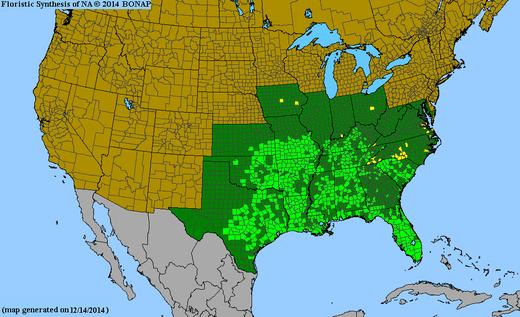

Meanwhile, Hickey and Anderson at the University of Wisconsin wondered if eggshells were thinning in North America, too. Their 1968 study, Chlorinated Hydrocarbons and Eggshell Changes in Raptorial and Fish-Eating Birds, measured eggshells of 13 raptors and 9 fish-eating birds and found that, yes, peregrine falcons were affected by DDT in the U.S.

Peregrine populations were crashing on two continents because of overwhelming nest failure in the face of DDT. Political and legislative wheels turned slowly. DDT was banned in the U.S. on 14 June 1972. Then the peregrine falcon recovery began. By 1999 peregrines were doing so well in the western U.S. that they were taken off the U.S. Endangered Species List. (**)

Museum egg collections played a key role in this happy result. It’s not a stretch to say that museums helped save the peregrine falcon.

(photo by Steve Rogers from the Section of Birds at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 2017)

(*) DDE is the toxic chemical formed when DDT breaks down.

(**) Peregrine falcons were taken off the PA Endangered List in 2021.

Just a reminder that I’m holding an Scavenger Hunt outing at

Just a reminder that I’m holding an Scavenger Hunt outing at